< Back to A level Cheat Sheets

A Level PHYSICAL Geography (Paper 1)

⚠ This is a work in progress, unfinished document. The most unfinished sections are marked with [tbd] and there may be general issues and typos. ⚠

please let me know if there are any errors :)

Latest update: 15/07/2023 11:06.

Last content addition: 07/06/2023 23:16.

✅ Note: This file is synced with this repository. This is the latest version.

Use a PC/device with a large screen to see the Table of Contents on the left-hand side to quickly navigate through this document.

Discuss with other students, developers, educators and professionals in the Baguette Brigaders Discord server! You can also receive a notification when there are new Cheat Sheets, Summary Sheets (new!) or other revision material is made public there!

For the entire specification, you can go here.

For only the human geography (paper 2), you can go here.

1.1 Option B – Glaciated Landscapes

“Feeling a little like a drumlin today.”

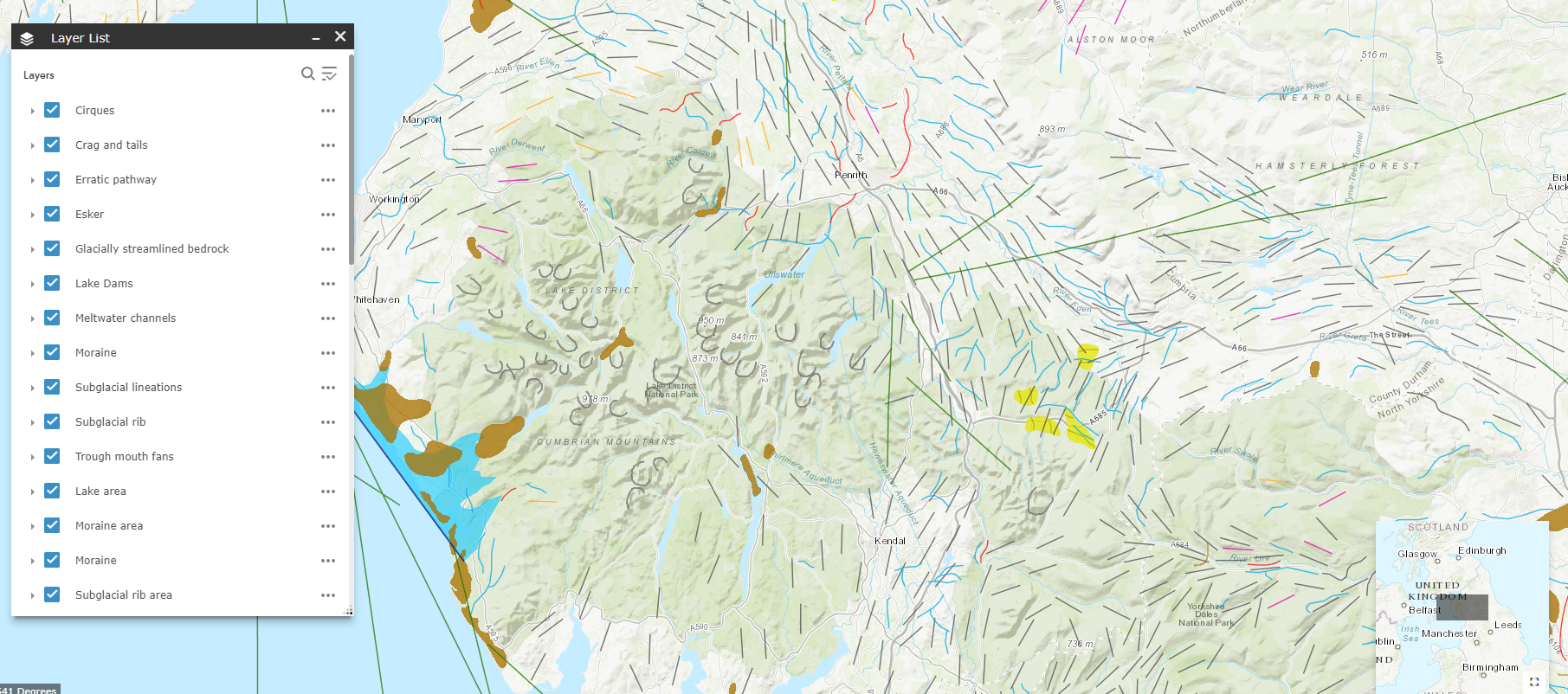

Check out this interactive ARCGIS British ice map to see places in the UK which have been influenced by glacial activity, with drumlins, subglacial lineations, moraines and more!

Glaciers as Systems

Photo from Simon Fitall

There are 3 main parts to any system: inputs, processes and outputs.

Glaciers are dynamic. Glaciated landscapes may be seen as a system with many interrelated components (stores), processes (cause/effect mechanisms) and inputs & outputs. This forms an open system.

- Inputs

- percipitation (snowfall)

- material from deposition, weathering and mass movement

- avalanches

- thermal energy (from sun)

- kinetic energy

- Outputs (Ablation)

- evaporation

- sublimation

- wind erosion

- meltwater

- Stores

- ice

- water

- debris

- potential energy (from its location)

- Throughputs/processes

- debris movement down slope

- deposition

- kinetic energy from glacier movement

Glaciers themselves can be seen as systems as they have a TON of different inputs, outputs, flows (or transfers) and stores.

Useful key terms

- Terminus - the end of a glacier

- Snout - the end area of a glacier

- Ablation - melting

- Calving - when chunks of a glacier terminus fall into water

- Advance - when a glacier is moving forwards; gaining mass balance

- Recession - when a glacier is retreating; losing mass balance

- Area of accumulation - the area of a glacier where it is gaining mass

- Area of ablation/wastage - the area of a glacier where it loses mass

- Névé - young, granular snow

- Firn - névé which has survived a full season (year) of ablation and is partially compacted, and has been recrystallised into a substance denser than névé, an intermediate stage to becoming glacial ice.

- Firn line/equilibrium line - the zone on a glacier where accumulation is equal to ablation over a 1-year period

- Sintering - continued fusion and removal of air as a result of compression by the continued accumulation of snow and ice

- Aspect - the direction that a slope faces.

- Azimuth - the compass direction of an object

The Glacial Budget and Mass Balance

A glacier forms when snowfall exceeds summer melt in an area, resulting in the accumulation of snow and ice year after year, typically in a hollow on a mountain with a northwest-southeast aspect in the northern hemisphere.

Over time, snow is compacted and turned into glacial ice, and when this is around 40m thick, the intense pressure causes it to begin flowing. The top of the glacier is white, but glacial ice at the base of the glacier is blue as oxygen has left the system.

Snowflakes -> Granular snow -> Névé -> Firn -> Glacial ice

Glacial ice has a density of 850kg/m3. It is rock hard and feels glassy and is almost translucent.

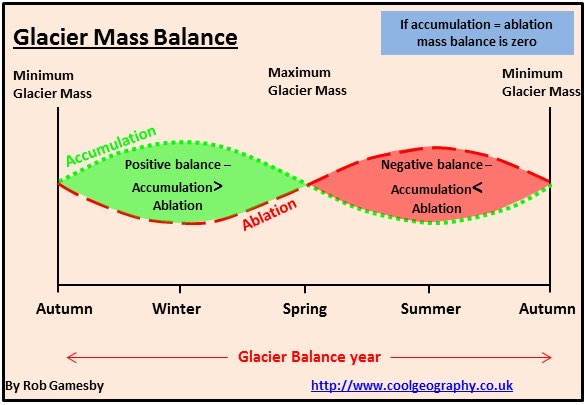

The glacier mass balance is the total sum of all the accumulation (snow, ice, freezing rain) and melt or ice loss (from calving icebergs, melting, sublimation) across the entire glacier, or ablation.

Over a year, the graph of mass balance in a northern hemisphere glacier may look like this in an ideal scenario:

An equilibrium is reached between accumulation and ablation are equal. This point may be reached between the accumulation extreme in winter, and ablation extreme in the summer season.

Layers of snow within the ice give evidence for the way that it has formed.

Types of glacier and movement

(Date studied: ~29/09/2022)

An ice sheet is a mass of snow and ice, greater than 50,000km2 with considerable thickness.

A piedmont glacier is one that spreads out as a wide lobe as it enters a wider plain typically from a smaller valley

A valley glacier is one bound by valley walls, coming from higher mountain, from a plateau on an ice cap or an ice sheet.

Ice cap - a dome-shaped mass of glacial ice usually situated on a highland area and also covers >50,000km2.

Valley glaciers usually occur in high altitude locations, with high relief, and have fast rates of flow at 20–200m/year and have distinct areas of ablation and accumulation, descending from mountains.

Ice sheets however, are large masses of snow and ice defined by being greater than 50,000 km² and are usually in locations of a high/low latitude and have slow rates of movement and only around 5m/year. The base of the glacier is frozen to the bedrock and have a little precipitation but also lower temperatures so ablation levels are lower too.

Fundamentally, glaciers move because of gravity. The gradient influences the effect of gravity on glaciers. Thickness of the ice, and the pressure exerted on the bedrock can also influence melting and movement. More accumulation also leads to more movement. When ice is solid and rigid, it breaks into crevasses (big gaps visible from the surface). Under pressure, ice will deform and behave like plastic (zone of Plastic Flow on the lower half of the glacier) making it move faster . Conversely, he rigid zone is on the top half of the glacier.

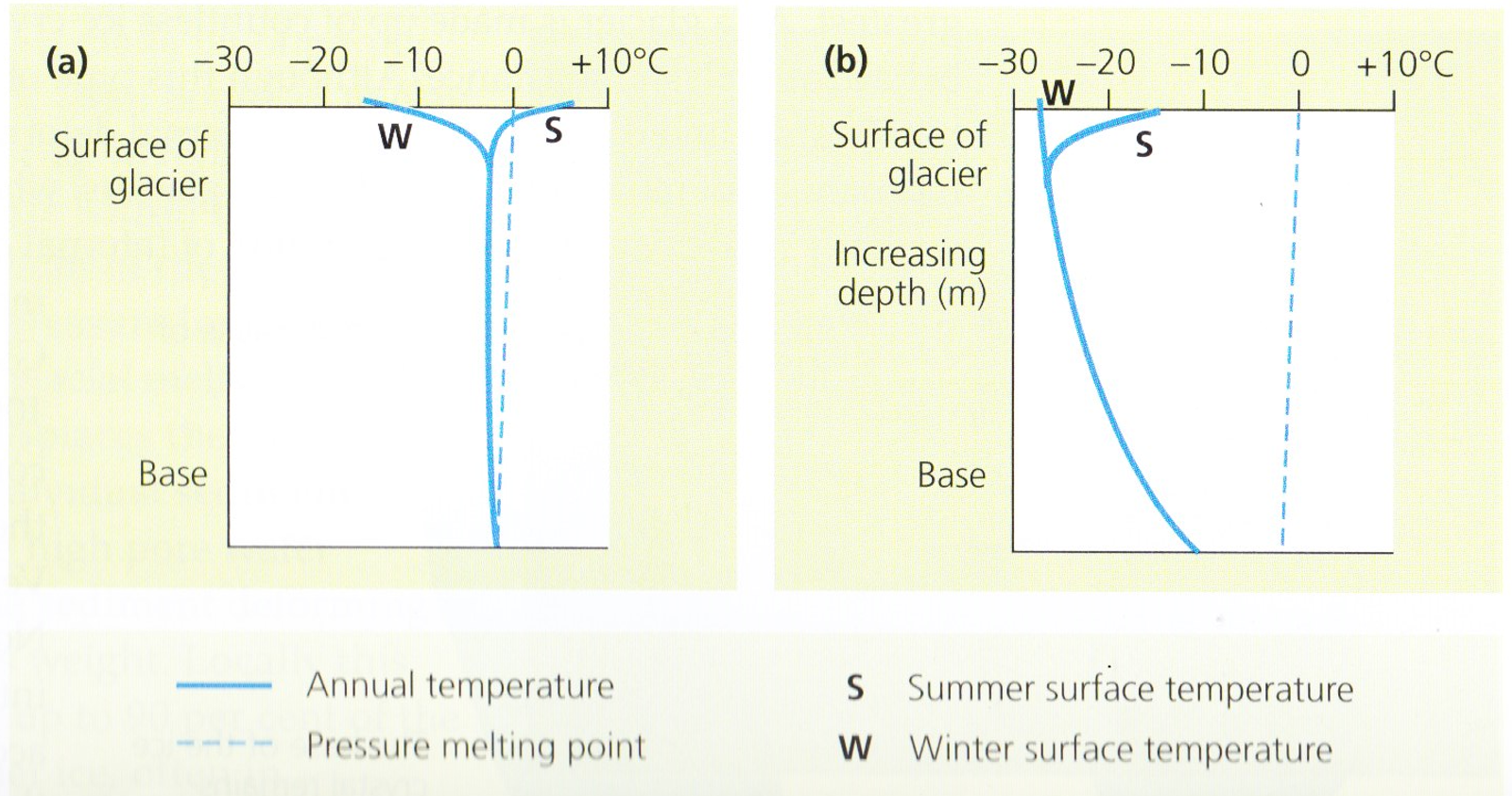

Cold-based glaciers:

- have a slow rate of movement (<5m/year);

- are located in extreme latitude (polar) regions;

- are flat in general;

- have a low basal temperature, remaining stuck to bedrock below the pressure melting point;

- are in low precipitation areas and the glacier remains below freezing point.

Warm-based glaciers:

- have rapid movement (20-200m/year);

- are located in high altitude (mountainous) regions;

- have a basal temperature at or above pressure melting point;

- have steep relief;

- have water present throughout, with ice acting as a lubricant.

Cold-based glaciers are unable to move by basal sliding as the basal temperature is below the pressure melting point. Instead, they move through internal deformation, and ice at 0°C deforms 100 times faster than at -20°C.

[tbd] Useful stuff

- Supraglacial material is material which is located on the top of a glacier.

- Englacial material is material which is located inside a glacier.

- Subglacial material is material which is located on the base of a glacier.

- Material deposited during glaciation is called drift.

- Material deposited directly by ice is called till

- Material deposited by meltwater is called outwash, or glacio-fluvial material.

Lodgement till is material deposited by advancing ice, due to pressure being exerted into existing valley material, and left behind as ice advances, such as drumlins.

Ablation till is material deposited at the terminus by melting ice from stagnant, or retreating glaciers during a warm period or end of glaciation event. Most depositional landforms are this type.

It can be known whether sediment was deposited by water or ice. Ice-transported sediment is angular, not curved, as it has not been subject to erosional forces by the meltwater. The order of size of sediments can indicate this too, as water deposits sediment progressively due to reducing energy levels, while glaciers deposit material unsorted and ‘en masse’. Glaciers deposit till in mounds and ridges too, as, during ablation, this englacial and supraglacial material gets dropped on the bedrock below. This is distinct from the layered deposition (or strata) typically characterised by fluvioglacial processes.

Factors affecting the microclimate

Regional climate

The wind is a moving force and is able to carry out processes such as transportation, position and erosion. In the air, these are known as aeolian processes, and can contribute to shaping glaciated landscapes.

The wind is a moving force and is able to carry out processes such as transportation, position and erosion. In the air, these are known as n processes, and contributes to shaping glaciated landscapes.

Wind is more effective when acting upon fine materials, usually those previously deposited by ice or meltwater, such as smaller rocks, dirt and sand.

Temperature within the climate is another factor, as temperatures above 0°C will melt accumulated snow and ice, resulting in more outputs in the system. At higher altitudes, there are typically more prolonged periods of above freezing temperatures, and melting, compared to in high latitude locations, where is below freezing most of the time, allowing for glaciers to thicken and expaensive ice sheets to form. Precipitation is another climate factor, with its totals and patterns, both regionally and seasonally, in determining mass balance of a glacier system, as it provides the main inputs to these glaciers as snowfall.

Geology

Lithology is the chemical composition and physical properties of rocks. Some types, like basalt, are very resistant to erosion and weathering, as they are comprised of densely packed interlocking crystals. Clay, on the other hand, is weak, and does not have these strong bonds on the molecular level. The solubility of rocks like chalk can also be affected by acidity, making them prone to chemical weathering as seen, through carbonation.

Structure relates to the physical rock types, like faulting, bedding and jointing. These all have an impact on how permeable rocks are. Chalk, for example, is very porous, spaces between the particles within it on the molecular level allow water to percolate through. Some types of limestone, like carboniferous limestone, has many interconnected joints, giving it ‘secondary permeability’.

Primary permeability is when spaces brackets (pores) absorb and retain water.

Latitude and Altitude

Beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, located at 66.5° north and south, the climate is very dry, with a little seasonal variation. Being so dry and extremely cold, they are much different to valley glaciers, which are more dynamic, as they have higher precipitation levels névé turns into firn. The dryness contributes to periglacial environments (see below for more about those!) while also turning the types of glaciers in these areas to more cold-based. This means that they flow much less quickly, and different types of movement occurs.

Altitude also has a direct impact on the temperatures and development of valley glaciers. As temperatures typically decrease by 0.7oC every 100m of altitude gained, there are more likely to be valley glaciers in areas of high relief, as seen in the Alps and in the Himalayas. These glaciers are still not as cold as cold-based glaciers however.

How are glacial landscapes developed?

Glacial landforms are typically classified according to erosional and depositional processes. This development can be described as a series of interrelated processes.

Glacial erosional landforms

Corries

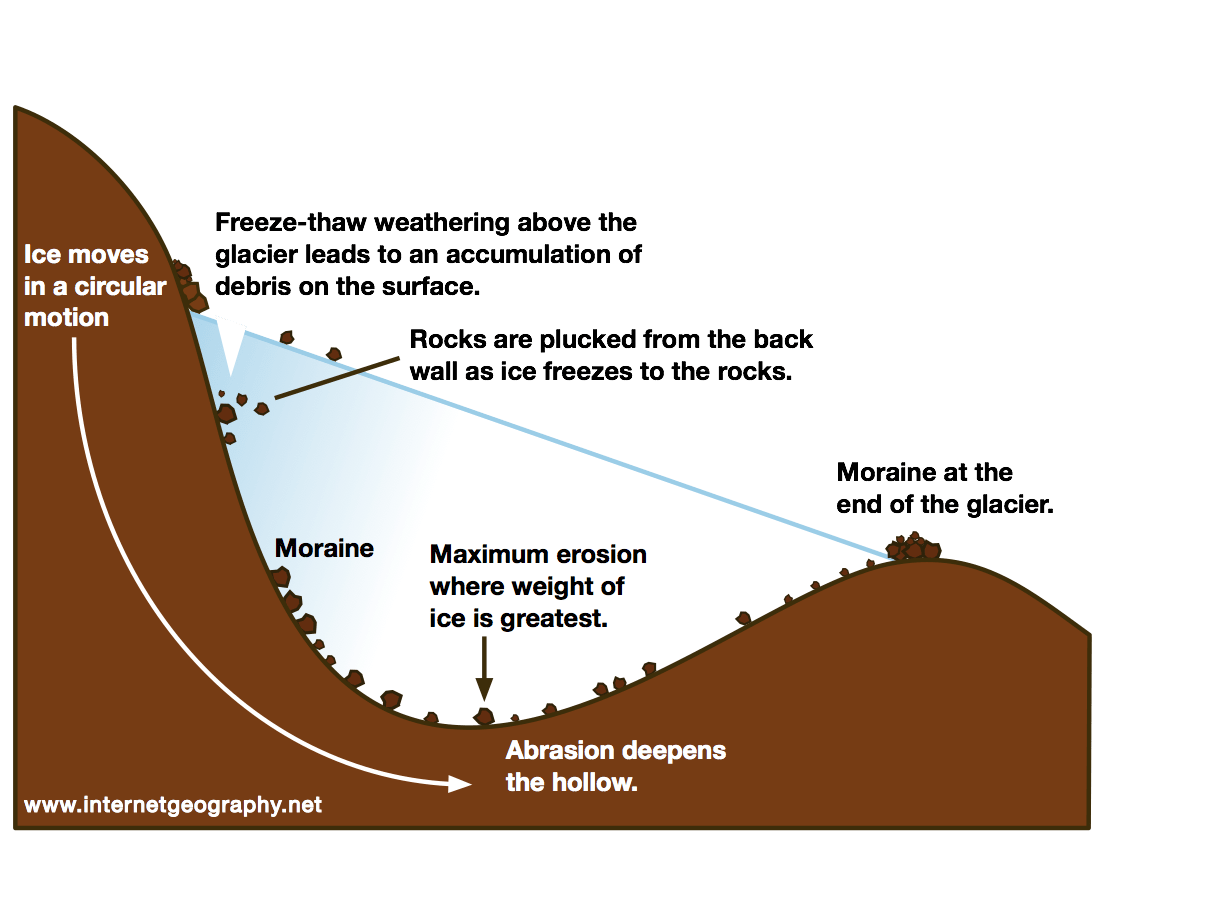

A corrie is an armchair-shaped depression in a mountain.=

Also known as a cwm or cirque, corries are formed from small hollows on the slopes of mountains where snow begins to accumulate, typically on the north-west to south-east facing slopes (or with an azimuth ranging from 300-140 degrees) on a mountain in the northern hemisphere.

This is due to its aspect, or the orientation of which a slope faces, with this specific aspect resulting in having less insolation. Greater amounts of irradiation adds thermal energy to the system, resulting in ablation.

This virgin snow turns is known as névé, which become firn after one complete cycle without melting (i.e. surviving a summer ablation period; 1 year). Over multiple years, the snow at the bottom is compressed into ice, and plucking begins to be the dominant process at the base.

This newly-formed hollow, deepened by the nivation (e.g. freeze-thaw processes) from the ice, then begins to move because of gravity acting upon the ice mass. The ice freezes to the back wall, plucking material (debris), which is then washed out through a process known as rotational slumping.

When this ice melts, a tarn (or corrie lake) is created, with potentially a rock lip created from washed out moraine or rocks forming at its front.

After the ice has melted and deglaciation has occurred, this material may then fall down from the back wall due to its aspect and steep relief, which is known as scree.

The processes occuring in a Corrie.

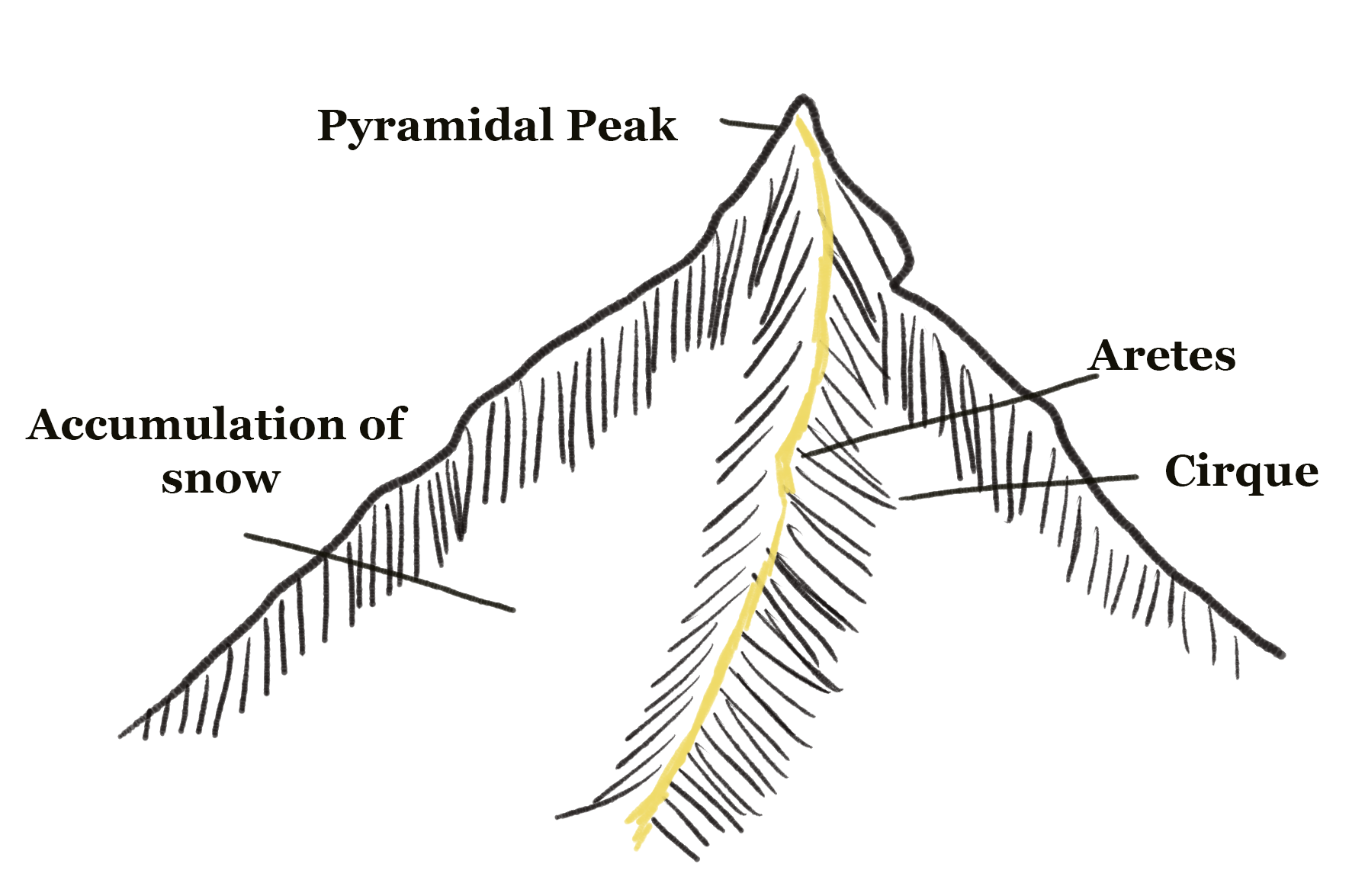

Arêtes

An arête is a knife-shaped, sharp ridge formed when two corries’ back walls continually erode back-to-back. Over time, these back walls meet, and a distinct ridge is formed.

A diagram of a mountain, which has had erosional processes acting upon it.

Pyramidal peaks

A pyramidal peak is a high mountain whose surroundings have been eroded as corries. Three or more corries eroding back-to-back (similarly to how arêtes form) results in this sharp peak forming. There are typically distinct ridges visible all the way to the summit, representing the boundary between corries.

The Matterhorn in the European Alps. It is a great example of a pyramidal peak.

U-shaped valleys

Also known as a glacial trough, a U-shaped valley is formed as a result of strongly channelled ice, bulldozing its way through a valley. On the valley’s sides, plucking occurs, causing the sides to steepen. This rocky material is then dragged by the glacier, helping it to carve out more of the landscape.

The actual shape of most U-shaped valleys are parabolic.

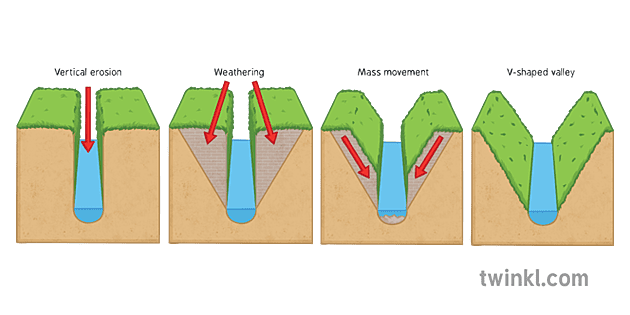

Firstly, before a glacial period, a V-shaped valley exists, having moderately steep sides and a central river channel, with interlocking spurs being a distinct feature. During periods of glaciation, snow begins to accumulate in these valleys as they are often sheltered.

How a V-shaped valley is formed. Remember this from GCSE? (if not, recap yourself on the GCSE cheat sheet!

When an ice mass has formed in the valley, or flowed from an upland area, freeze-thaw weathering begins to occur above the glacier line (where this ice mass is), causing the valley to steepen, in the same way as a corrie steepens its back wall. The glacier itself also causes plucking, mostly on the sides, as rocks are frozen and ripped as the glacier moves. Vertical abrasion also deepens the valley floor as subglacial material comes into contact with the bedrock.

Hanging valley

Hanging valleys with waterfalls and truncated spurs are a feature of the U-shaped valley landform. They are visible within this glacial trough, and form as a smaller glacier from another valley has created a U-shaped valley which then enters the larger valley. As the hanging valley’s glacier is smaller, it is less powerful, so it does not reach the base of the larger glacial trough valley.

Photo from Peter Hammer.

Water features

After deglaciation, there may be some (iconic) water features in these glacial troughs.

Ribbon lake

Vertical erosion typically leaves the floor of a valley glacier system relatively flat, and deeper than in preglaciation periods. This depression (or rock basin) is then refillid with water after a glacier retreats.

These lakes show the path of a glacier, typically during times of compressing flow (more detail in the case study below).

Misfit stream

A ribbon lake as well as a misfit stream may also be present in the base of the newly-formed glacial trough valley after deglaciation.

Misfit stream: Photo from Mario Álvarez.

Roche moutonnées

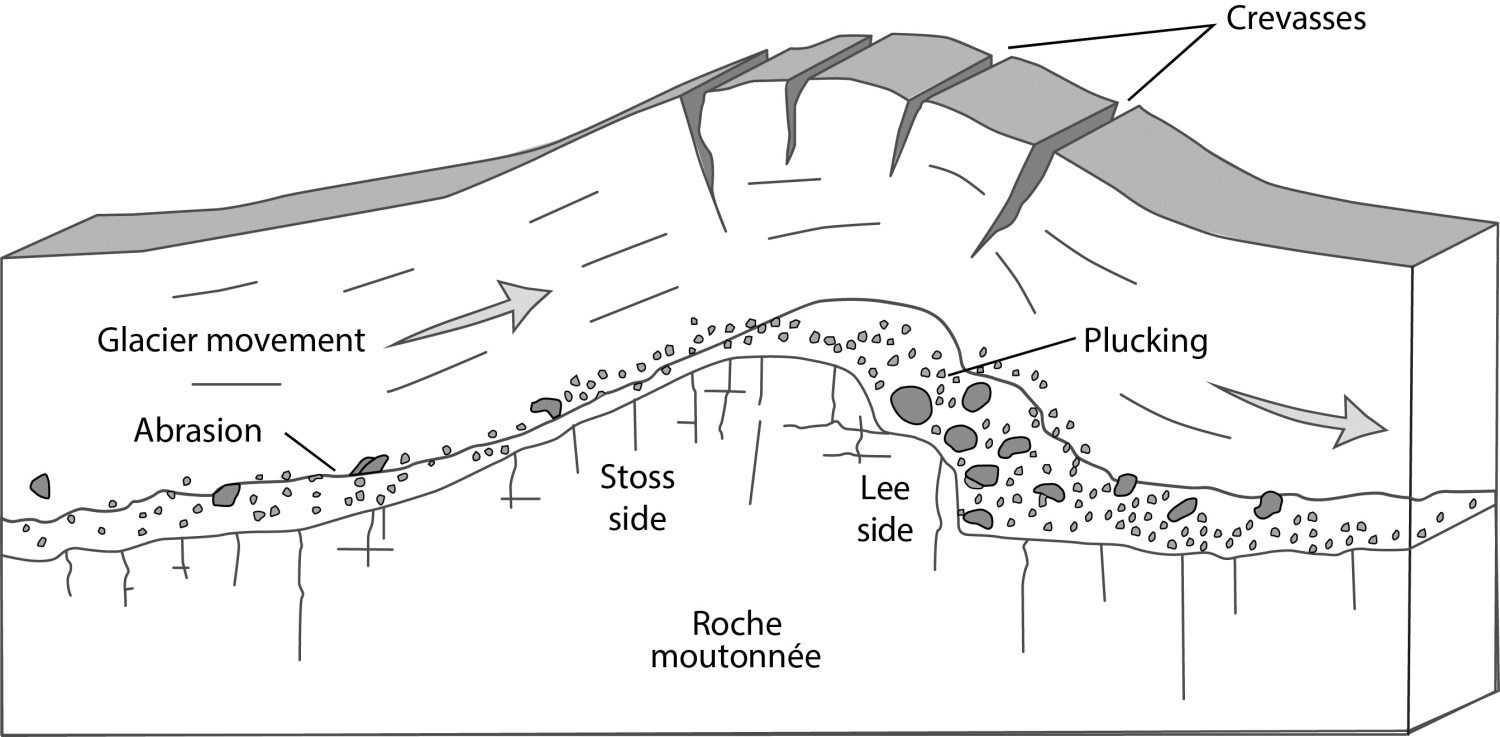

A roche moutonnée is a more resistant rock in the path of a glacier. Light abrasion from the above subglacial material occurs on the upvalley (stoss) side, resulting in striations, grooves, and polishing from subglacial debris. There may also be pressure melting at a local scale on this side.

As this meltwater is forced up and over the roche moutonnée, mechanical plucking and freeze-thaw weathering occurs. On the downvalley (lee) side, the pressure release results in refreezing into ice, while the glacier continues to move, thereby pulling away the rock.

Roche moutonnées are generally concentrated in areas of competent bedrock, such as granitoids (Glasser, 2002).

Source: Québec government website

The word is French with “roche” meaning rock and “moutonée” meaning sheep.

More specifically, it was introduced by a French geologist called Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799). The word is called like so due to its resemblance to the shape of a wig worn by 18th century French aristocrats which shaped their hair like a wave. Sheep fat was used to hold the wig in place, which explains the term moutonné (Benn and Evans, 2010). In Sweden, very large roches moutonnées are called flyggbergs, with some being up to 3 km long and 350 m wide (Rudberg, 1954; 1973; Iverson et al., 1995; Benn and Evans, 2010).

(Epically translated by me, you’re welcome.) [2]

Ellipsoidal basins

These are no ordinary valley or alpine glacier erosional landform. These are huge areas formed by ice sheets such as the Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America. (more detail with the Ice Sheet Case Study)

These huge ice sheets (more than 50,000km2) exert large amounts of pressure on the landscape as well as great erosional quarrying by subglacial material. Examples of this feature include Hudson Bay, and smaller ellipsoidal basins created the Great Lakes in North America.

On top of the subglacial erosion which may have occurred, the majority of the landscape’s (yes, I’d say the’re larger than just landforms) formation is due to isostatic lowering. This involves the sheer mass of the ice sheet, potentially several kilometres thick, exerting pressure on the lithosphere and effectively compressing it into being smaller.

After deglaciation, isostatic readjustment may occur, and these compressed, lowered areas may readjust, now being under no additional pressure.

[REVIEW] Admin note: this must be fact checked and reviewed to ensure clarity and precision!

Glacial depositional landforms

Moraines

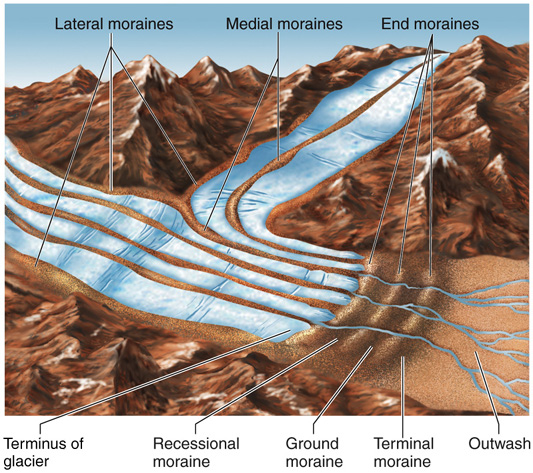

Moraines are ridges of soil, rocks and till which have been deposited by a glacial system.

Medial moraines

Form in the centre of a glacial channel (typically when two glaciers merge - see image above and you can see how the mountain in the middle is being carved out). Also may occur when their lateral moraines meet and combine into one.

Lateral moraines

Ridges which form on the sides (margins) of a glacial channel, and are the result of the accumulation of debris due to erosional processes.

End moraines

These mark a pause or halt of glacial retreat (e.g. when there are a couple of decades with little advance or retreat). These pauses typically are not very long so deposits reflect this, not being too large either (100m max)

Terminal moraine

A ridge, often characterised by being largest and most prominent in the area, marking the maximum advance of a glacial period (glacial maximum), deposited at the snout of the glacier. Often cresent in shape when observed from the cross profile.

Recessional moraine

A combination of the end and terminal moraines.

Erratics

They are randomly placed bits of rock and other debris which can be characterised by being of a different geology compared to that of surrounding rocks, e.g limestone in a valley mainly of basalt.

This can be seen in the Lake District where rocks belonging to the rock group Borrowdale Volcanics were found in an area dominated by limestone.

The Bowder Stone is another example being a 2,000 ton andesite lava boulder south of Keswick in the Lake District which most likely originated in Scotland.

Drumlins

Drumlins are unsorted mounds of streamlined till, commonly elongated parallel to the former direction of ice flow, composed of glacial debris.

It is not known exactly how drumlins are formed, but the most likely and agreed upon explanation for their formation is that the glacier becomes overloaded with till (loses comptence), so begins to deposit this sediment due to the increased friction that the till brings (‘smearing’ the landcape). This sediment accumulates and quickly compounds, and other till that flows over the initial bump can become stuck, growing this mound of unsorted till. Over time, this grows, and when the glacier retreats, the distinct hill is revealed.

This is an example of lodgement till (not ablation till) as it is formed as the glacier is still advancing.

Others argue that they may have a bedrock core (are hence rock-cored drumlins) and as material was obstructed, sediment began accumulating around this, much like in the way of a dune, and was streamlined in the same way as above.

They typically occur in larger groups, or ‘swarms’. This is known as a ‘basket of eggs’ topography.

Drumlins can be up to 1,000m in length but are typically around 300-500m. They also improve revenue for farmers, as the topography allows them to have a larger farming area in the same sized plot of land. Their length to width ratio is typically between 1.8 and 4.1, and this may be an indication of past glacial velocities, with longer drumlins indicating a faster ice velocity due to the laminar flow of ice.

Drumlins are often found in conjunction with morainic landforms and other depositional features like eskers, kames, outwash plains and

I’d love to be like a drumlin one day, they’re just so chilled out and calming

Did you know that the ground between two drumlins is known as a dungeon?

Theory of depositional drumlin video

Ribbon lakes

Ribbon lakes are both depositional and erosional. They are formed by the combined processes of glacial erosion, which deepens and widens the valley floor, and glacial deposition, which leaves sediment along the shores of the lake.

Glaciers erode the valley into the typical U-shape. These lakes are typically long, thin and deep as a result of compressing flow, as this ice is likely to have come from an area of high incline to a more expansive area. This means that the ice is more likely to move faster and pushed into a thinner area downstream, so is more likely to erode vertically rather than laterally. More detail over at the ullswater case study.

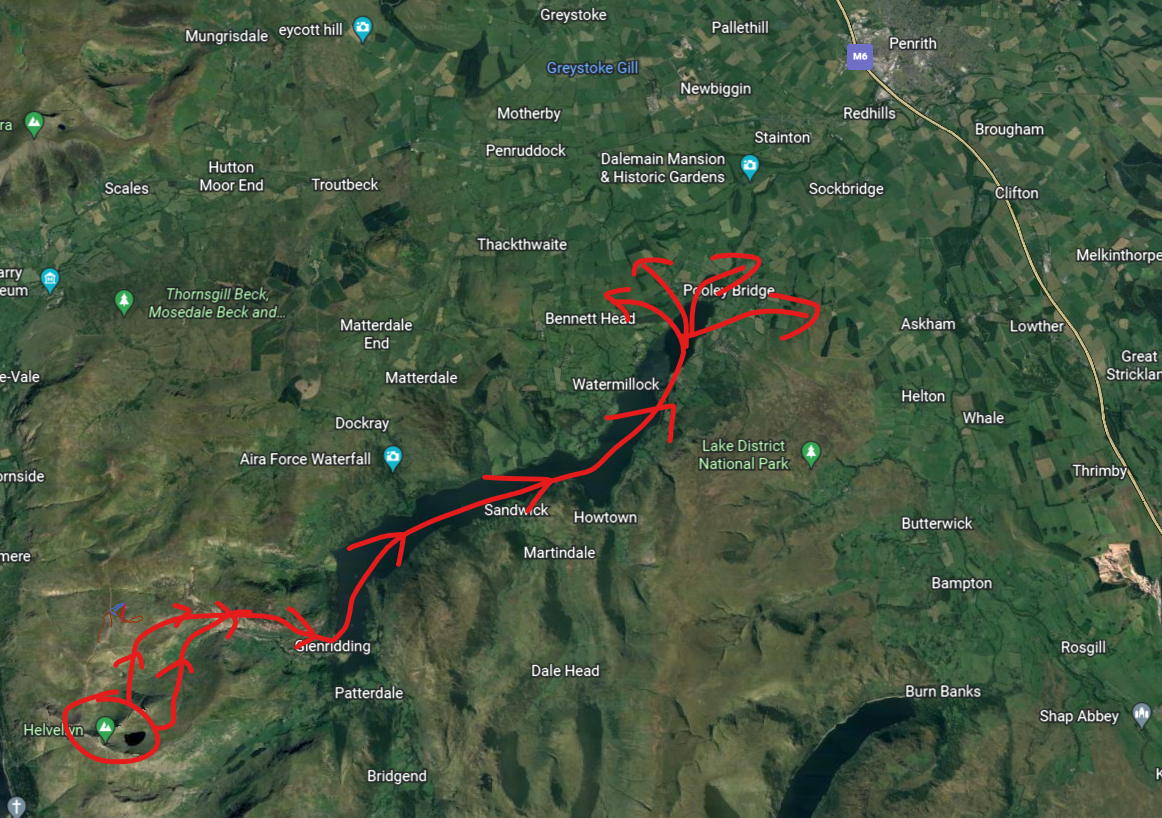

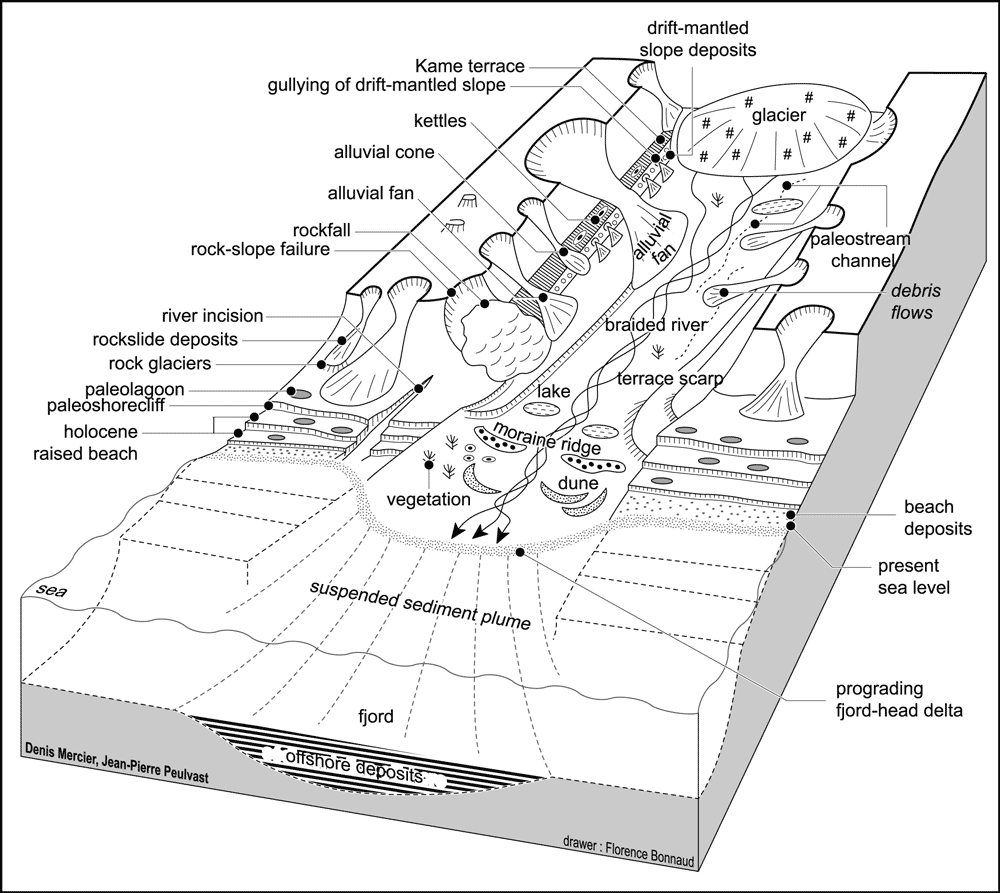

[tbd] Case study: Lake District

Glacial features of the Lake District, including subglacial lineations, meltwater channels, eskers, drumlins, moraines, glacially streamlined bedrock and more.

Glenridding Valley & Ullswater

Ice from Red Tarn at Helvellyn flowed north-east into Glenridding Valley. Joining up with another larger glacier, a glacial trough was created in present-day Ullswater. Exacerbated by compressing flow, where the ice mass moves slower, a long, thin, deep ribbon lake formed (as the flow made ice more likely to erode vertically).

This glacier would have continued flowing downstream towards modern-day Penrith, which is in a flat plains area, possibly resulting in the old Ullswater glacier becoming a Piedmont glacier when entering this more expansive, larger valley.

Inside modern day Ullswater is a series of roche moutonées such as Norfolk Island and Lingy Holm. The geology of roche moutonées is characterised by being more resistant than other local rock types, possibly with increased jointing and bedding, resulting in striation lines with the freeze-thaw weathering being visible on the lee side still today on these rock islands.

The Glenridding village has visible depositional till extending into Ullswater, visible from satellite imagery, easily proving that there was once glacial activity in the area.

As you can see, there is material extending into Ullswater from the valley leading down from Helvellyn. This shows that there was substantial amounts of debris that was being deposited and moved along this glacial route.

Essay snippet: inter-related valley landforms [16 marks]

A corrie, or cirque, is formed by snow falling and compacting in a hollow over many winters, typically on the northern side of mountains in the northern hemisphere due to the sheltered aspect, and cooler microclimate. Over time, snow accumulates, compacting the snow beneath it into ice due to the air inside being displaced. The back wall of the mountain, for example Helvellyn in the Lake District, gets increasingly steep due to persistent freeze-thaw weathering and plucking of material, which then gets entered into the young glacier system as englacial material, or landing on the surface as supraglacial material.

At the same time, under its own weight, the ice at the base begins to rotate, known as rotational slipping, deepening the base through abrasion, with this abrasive material being finer sub-glacial debris. At Helvellyn, the bedrock type is known as the Borrowdale Volcanics, having formed 450 million years ago and moved from tectonic forces. Despite this relative strength due to its more joined and bedded geology, several corries have formed, and their contained glaciers have melted throughout the Pleistocene period. After the most recent glaciation period known as the Loch Lomond Stadial around 12,000 years ago, there exists a corrie containing Red Tarn on Helvellyn’s north-easterly side. These corries have eroded back to back, resulting in the formation of an arête, shaped like a knife, namely Striding Edge, and Swirrell Edge on the alternate side of this corrie. Furthermore, Red Tarn has a lip, helping to prevent water loss, as a result of rock and moraine deposits left by the glacier.

These examples clearly show the significant extent that which landforms in a valley glacier system are interrelated between different erosional landforms, from the initial snowflakes settling in a hollow to the creation of many other landforms during and after glaciation has occurred.

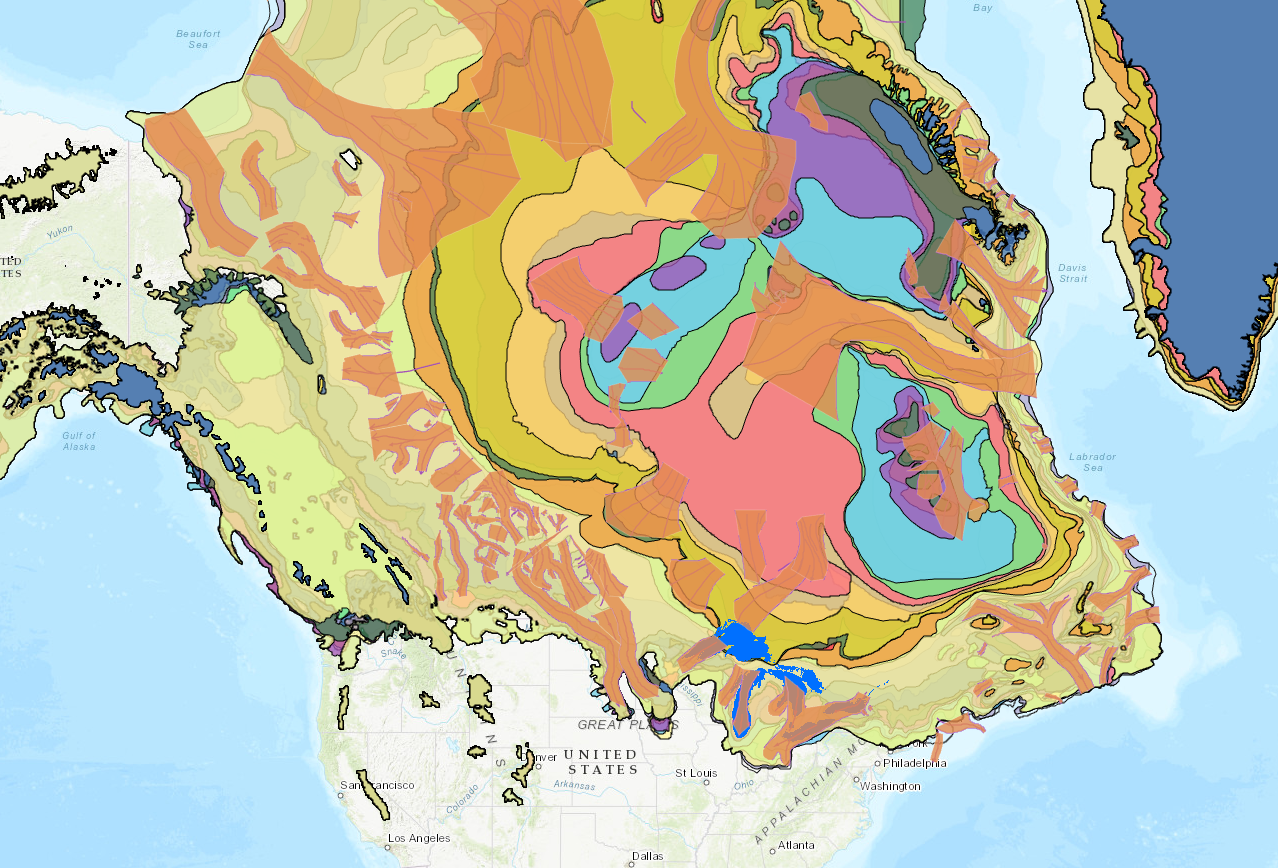

Ice Sheet Case Study: Minnesota

The Laurentide Ice Sheet during various glacial stages

An interactive map of glacial extent and lobes is available here.

Wadena lobe

The Wadena Lobe had depositional impacts on the north-west of the state. Its deposits were red and sandy, derived from red sandstone & shale rock in the north and the north-east of Canada.

It first deposited the Alexandra moraine, which resulted in drumlin swarms over three counties including the Wadena county itself as well as Otter Tail and Todd counties.

It also deposited the Itasca moraine series which has similar features.

At its glacial maximum, it reached just south of Minneapolis.

Rainy and Superior lobes

The rainy lobe moved in after the Wadena lobe in the same general area, but only covered half the area. However, the Superior lobe was much larger and moved in from the north-east. It partly covered the modern-day Lake Superior, on the east side of the state.

Their last glacial advance deposited coarse till which contained various types of basalt, gabbro, granite, red sandstone, slate and even greenstone. The red sandstone made the overall deposits seem reddish and dusty-looking.

Deposits can be found across the north-east half of Minnesota, stretching as far south as Minneapolis.

Like Wadena, it too deposited drumlins.

Des Moines lobe

Moved in from the north west, covering vast expanses of the west of the county from the most northerly point to the most southerly point. It deposited till that is tan to buff coloured and is clay rich and calcareous due to its shale and limestone source in the north east.

In the south west, Prairie Coteau is an example of a terminal moraine.

Many of its deposits are over 160 metres deep.

Erosional impacts of the ice

The highest mountains in Minnesota were worn down from being made of metamorphic gneiss and many kilometres high, now they’re just 500 to 700 meters in elevation.

Furthermore, a large ellipsoidal basin was created and contains thousands of lakes like Upper and Lower Red Lake in North Minnesota, and Mille Lacs Lake in Central Minnesota.

In the Arrowhead Northeast region, this erosion was especially deep due to earlier tectonic tilting of the landscape which exposed weak shale rock. Lakes here lie in deeply eroded shales.

Deglaciation - Lake Agassiz

Glacial Lake Agassiz was formed by glaciers which blocked the natural drainage of the area and as a result a lake developed to the south of the ice. The river that drained Lake Agassiz was known as Glacier River Warren. This left behind fertile silt deposits in what is now the Red River Valley.

The water is then thought to have overflowed at Brown’s Valley and cut the present Minnesota River Valley, described as a glof, a glacial lake outburst flood. This discharge was staggering and also helped form the adjacent Mississippi River.

Glacial Lake Agassiz was a large glacial lake located in central North America. It was formed by contributory meltwater from the Laurentide ice sheet, which was up to 2 miles in height. When an outburst flood occurred, around 13,500 and 10,650 years ago, it resulted in large scale erosion of an area 8km wide and 76m deep in Browns Valley, Minnesota. This old river is known as the Glacial River Warren. It helped form the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers.

This event may have had an impact on the climate, global sea levels, and potentially even early human civilisation!

The top right is the bed of Lake Agassiz, and the eroded area is visible too. North Minnesota.

Post-glacial modification

The present landscape of Minnesota resulted largely from glacial activity in the Quaternary Period, or the most recent 2 million years. The Laurentide Ice Sheet grew and retreated several times over this period.

Isostatic readjustment occurs when these ice sheet glaciers retreated due to the land not being under pressure anymore. This land then typically rebounds upwards and elevations increase in the area where glaciers once lay. Fluvial activities continued to mould the landscape after full glacial retreat had occurred.

Glacio-fluvial landforms

(Date studied: 23/11/2022)

Glacio-fluvial means an environment shaped by glacial meltwater.

Geomorphic means changes (morph) to the land (geo).

Note: The influence of climate change is also required for all these landforms. This does not mean present-day climate change - rather, climatic shifts that have occured throughout the past and Pleistocene epoch, from warm interglacials to cooler stadials.

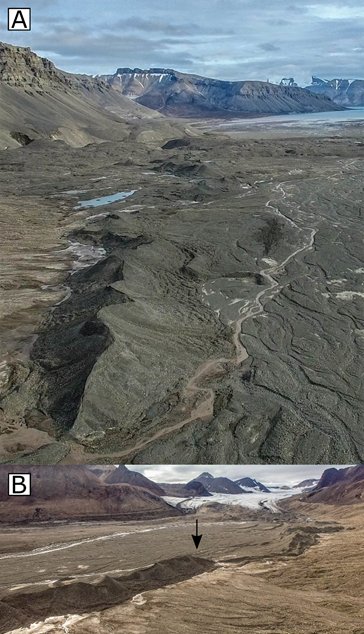

Eskers

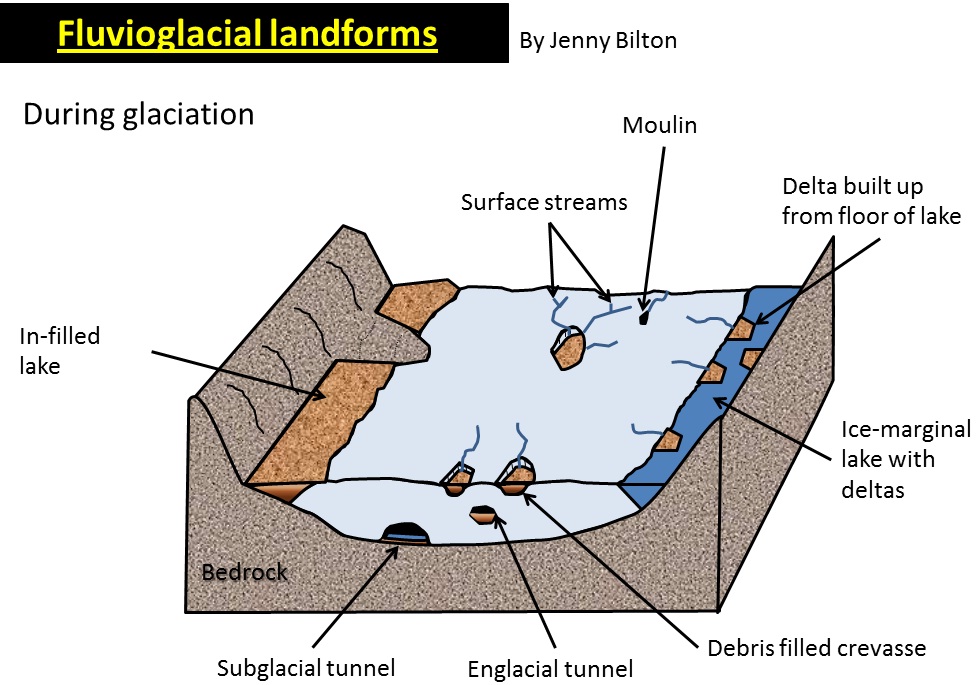

Eskers are long, sinuous (many curves and turns) ridges made from sand, gravel and other types of glacial till deposited on valley floors by glacial meltwater flowing through subglacial and englacial tunnels.

Eskers are “elongated ridges of glaciofluvial sediment deposited by subglacial meltwater pipes”.

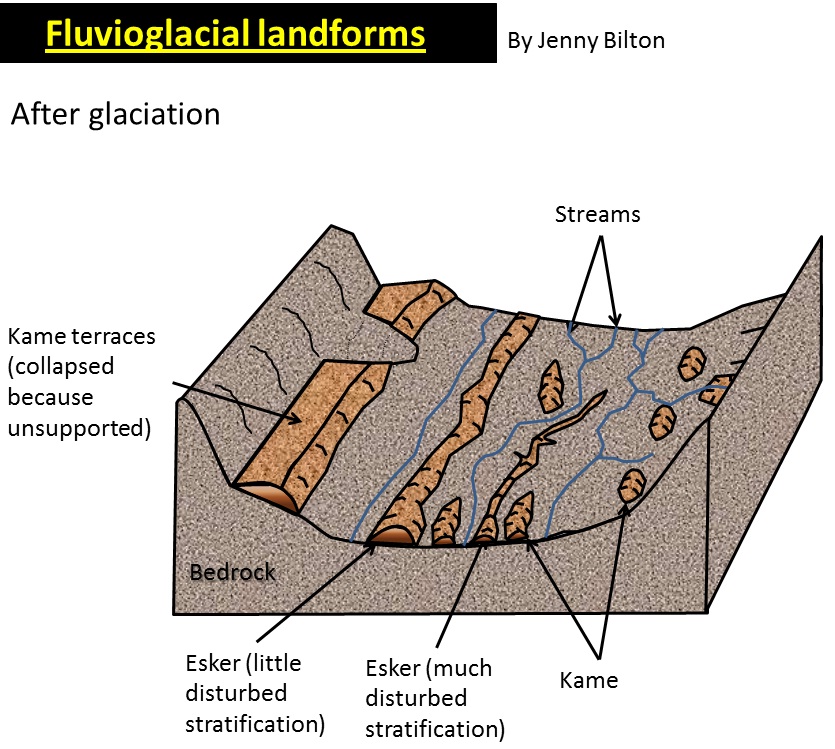

These tunnels and channels over time become filled up with sediment. During deglaciation, this sediment is dropped onto the bedrock leaving stratified ridges, signifying that a glacial meltwater tunnel was somewhere above it. This could be either a kame (see below) or an esker.

The general consensus is that the deposition is caused when pressure is released at the glacier’s snout, so as the glacier retreats, the point of deposition retreats too. This can describe their beaded appearance (vary in height and width throughout) with the beads of greater size representing periods of relatively slow retreat, or halted ablation. Others may say that the larger beads are caused as a result of greater load carried by the meltwater in summer seasons.

Here’s 2 angles showing what they look like, in Svalbard.

The weight of the ice above the subglacial tunnels mean that the water flowing within these subglacial tunnels is under extremely high pressure. When the ice melts, this pressure is released, so therefore dropping sediment.

Eskers are deposited unaffected by/ignorant of local topography, meaning that they can traverse over hills in the landscape.

The path taken by this pressurised meltwater is mostly controlled by the slope, size and direction of the ice surface rather than the bedrock. Because of this, eskers can be used to show the slope of the ice surface, as well as its extent! It also runs parallel to the direction of ice flow, running transverse to the glacial snout.

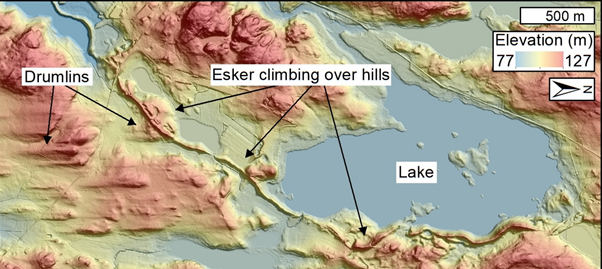

Topographic view of depositional landforms.

Eskers on paleo-ice-sheet beds are more abundant in areas of crystalline bedrock with thin coverings of surficial sediment than in areas of thick deformable sediment, because meltwater flowing at the bed is more likely to incise upwards into the ice to form an R-channel where the bed is hard; where the bed is deformable, meltwater is more likely to incise downwards.

You don’t need to remember that.

Examples

Many eskers are found in central Ireland, some are in Canada, as well as many in Iceland and Sweden.

Here is an example of an esker on Google Maps.

A meltwater stream is visible south of it, as well as another esker to the east.

Post glacial climate change in Eskers

During periods of increasing global climatic temperatures, the rate of glacial ablation increases and results in more meltwater being produced. This means that there is more accumulation of sediment in proglacial areas and the length of these eskers is likely to increase, or become more beaded with greater and more intense ablation periods.

Kames and kame terraces

A kame is an irregularly shaped hill, hummock or mound made of stratified glacial till comprised of mainly sand and gravel.

There are two types of kame

Delta kames

Delta kames can form in two main ways. Firstly, they can form due to the build up of debris in englacial tunnels that emerge at the glacial terminus ass a result of retreat. As a result, they lose their energy, and are forced to deposit their contained load.

Another way that they can be formed is when supraglacial streams meet ice-marginal lakes. These ice margin water bodies are largely static (just sit there tbh) so the sediment they carry loses energy and gets deposited in the lake, from where this supraglacial stream enters it, often leading to a tall accumulation.

Kame terraces

Kame terraces are ridges of material near or on the valley margin. They are largely comprised of ex-lateral moraine, which was transported into the ice marginal lake due from the supraglacial streams formed due to the warming of ice through friction with valley walls. As this is largely glacio-fluvial, unlike morainic deposits, these are somewhat sorted and stratified by the movement of water. When the glacier retreats, this sediment is dropped and collapses onto the bedrock floor.

Watch out! Many people say ‘kame’ when they mean ‘esker’! You need to know the differences between the two well. (main one is eskers are subglacial, kames are not)

This displays the distinction between kame and esker.

As climate change increases temperature levels, more meltwater is present, which transports and deposits sediment. This will result in a larger amount of all types of kame being more likely to form.

Essay example: influence of climate changes and geomorphic processes in their formation

Kames are are mounds of sediment deposited by glacial meltwater or ice, found in areas where glacial ice melted and receded, leaving behind sediment deposits. The process of kame formation is complex, and is a result of a variety of interrelated factors, including climate change and geomorphic processes.

Climate change is one of the most significant influences on the formation of kames. During the Pleistocene epoch, large areas of the northern hemisphere were covered in thick glaciers. As the climate warmed and the glaciers receded, large volumes of meltwater were released, carrying sediment with it. The sediment was deposited in stratified piles, forming these kames, visible in places in the UK such as the Scottish Highlands or the Lake District. This can be proven to be the result of a glacio-fluvial deposition as they are deposited in one go by melting ice, while previous meltwater surface stream moved the sediment into crevasses or glacial marginal lakes.

Geomorphic processes also play a role in the formation of kames. As the glacier erodes the landscape, valley sides’ sediment may fall onto the glacier, ranging from large boulders to sand grains. The size and shape of these kames varies depending on the type of sediment deposited, as well as the rate of erosion. In addition to erosion other geomorphic processes can play a role in the formation of kames such as weathering. These processes such as frost-shattering and chemical weathering can break down sediment particles and form smaller particles that can be easily carried by wind or water. This can cause further accumulation of sediment in certain areas and contribute to the formation of kames. Lithification may also occur when the sediment is compacted and cemented together, forming a solid mass among the trapped sediment.

In conclusion, climate change and geomorphic processes are both important factors in the formation of kames. Climate change causes the glaciers to melt, releasing large volumes of sediment, which is then deposited in strata. Geomorphic processes, such as erosion, sedimentation, and lithification, also contribute to the formation of kames. Together, these two factors contribute significantly to the formation kames, alongside many other factors like the topography, aspect and relief of the local region.

Proglacial lakes

Proglacial lakes form in front of glaciers, usually when meltwater streams become blocked by terminal moraines, glacial dams (trapped against a large ice sheet) or due to isostatic depression of the lithosphere into the weaker asthenosphere.

The meltwater, over time, accumulates in this area, unable to flow outwards. This is similar to how a traditional valley glacier system starts with the corrie melting and a tarn being left due to a terminal moraine blockage.

After a glaciation period, the climate typically warms up. Over time, if there is a large ice sheet blocking the water flow, this sheet will ablate, and the lake will either overflow or undermine the dam, causing a glacial lake outburst flood, or jökulhlaup.

Modern example: The Russell Fjord in Alaska is regularly blocked by the Hubbard Glacier, which can increase water levels in the fjord by up to 15m as it cannot empty out into Disenchantment Bay: Google Maps/3D Google Earth.

Outwash plains

Outwash plains are also known as sandurs. They are dominated by other landforms, including braided streams and kettles. They occur in front of melting glaciers, and are mostly flat and expansive areas. Meltwater traversing this terrain has little energy, and therefore little vertical erosional power and more inclined to deposit material. As a result, these flat areas are created from stratified (strata; layered) sediment.

As the glacier moves over bedrock, plucking and abrasion (erosion) occurs resulting in silt and sediment being carried in this meltwater. Braided streams are dominant in outwash plains. These are very shallow streams and rivulets which carry and redeposit till due to the little energy in the system.

In summer months, there is typically higher glacial discharge and ablation, resulting in these tilly islets being destroyed by water, which has a little more energy due to increased velocity. This leads to more erosion, and these islets then go on to reform later. This makes the outwash plain have a distinct look. This can be described as dynamic.

The elevated level of erosion is typically closer to the glacial snout but then progressively loses energy.

In areas that were once glaciated, old outwash pains can be found by looking for sediment, with large angular rocks and boulders being present closer to the glacial mass and smaller, smoother rocks and sediment being further away from the glacier, similarly to a typical river system aside from their origin. Outwash plains can extend for miles beyond the glacial margin (terminal moraine).

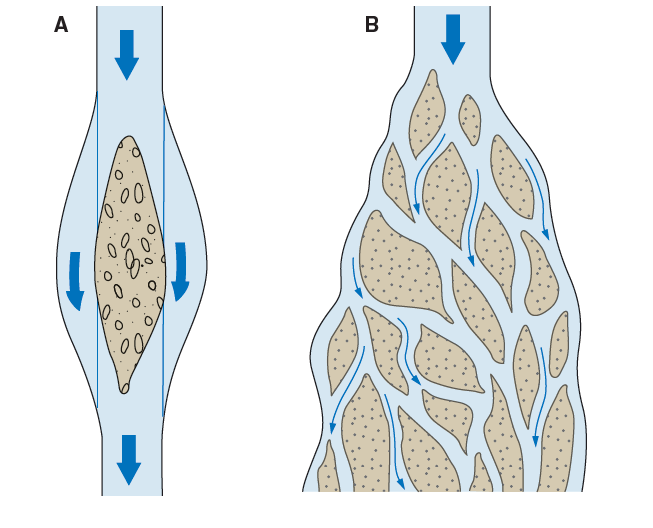

Braided streams

The general consensus is that braided rivers form instead of meandering rivers due to a higher sediment load, caused by discharge from ablation, as well as variable rates of flow. At the end of a melting period, these lose water, lowering kinetic energy present in the system and therefore losing erosional power and increasing depositional power.

This results in material being deposited into the river channel, causing it to divide in two. Braiding itself develops when this ‘mid-channel bar’ grows downstream, as a result of more, finer material being added to the bar as discharge amounts continue to decrease. These bars, during times of exceptionally low discharge like in winter months, may become home to vegetation, becoming even more permanent. whereas unvegetated bars are less stable and often move with high discharge.

Many of these channels branch from other channels and merge to give it the ‘braided’ pattern. They are common in outwash plains due to the variable nature of ablation and meltwater amounts.

diagram of a braided stream

They are found in large quantities in south Iceland, for example.

Due to climate change, braided streams may dry up due to smaller amounts of ice present in these areas, after an initial increase in ablation due to temperature rise. This initial increased sediment load will progressively decrease as the ice mass decreases.

As a result, there can be expected to be more eroded streams, being deeper and wider, inside this outwash plain, followed then by the area becoming dry and tundra-like. Whilst vegetation thrives in outwash plains due to the rich minerals present in the glacial meltwater, this may also dry up in the future, becoming a barren, sandy and gravelly area with little life, or could be taken over and reclaimed by plants depending on resource availability.

Is that a braided stream AND a proglacial lake inside a valley glacier system?

Photo from Jonas Mendes.

Kettles

A kettle is a large depression in the ground formed by glacial deposition, and is therefore a depositional landform. They create ‘dimples’ in the landscape around mountainous areas.

They are formed by large blocks of ice breaking from the main glacier. As the main glacier retreats, this ‘dead’ ice becomes stranded and, over time, becomes buried by sediment deposits as meltwater flows around it from the main glacier. Of course, this ice melts and its water evaporates, leaving behind a large depression, or kettle holes. Water can then fill these in again, or if not all water drains originally, resulting in kettle lakes.

Periglacial landforms

Periglacial landforms exist as a result of climate changes before and/or after glacial periods.

Periglaciation is concerned with the process and landforms attributed to the action of permafrost.

Being in a periglacial area means an area that is near to, or on the fringe of, glacial areas’ ice mass. This means that there is no physical glacier system present in the area, but it is still cold, relative to surrounding environments.

Permafrost

This is also part of the Earth’s cryosphere, as well as glaciers, ice sheets, and more!

Permafrost itself is comprised of:

- the active layer (this is the top few metres or so. It is warmer as it is closer to the surface. It may become unfrozen during the summer months and vegetation may grow too.)

- the permafrost layer itself

- talik (year-round sections of unfrozen ground, soil, rocks that lies in permafrost areas, but itself is not frozen)

There are 3 types of permafrost:

- Continuous permafrost: there is little thawing, even in the summer. These are often in areas of high altitude and latitude.

- Discontinuous permafrost: There are some patches of consistent permaforst, but are broken up by talik extending to the active layer

- Sporadic permafrost: small amounts of permafrost largely enclosed by talik

Patterned ground

This encapsulates sorted stone polygons, stone stripes, etc.

These landforms are facilitated the process of frost heave. Stones within the ground and active layer have a lower specific heat capacity, allowing them to cool down and heat up faster than their surrounding soil. Due to the freezing conditions, water below the stones freeze as well, and also expanding by 9%, pushing the stones upwards. Over time and many years potentially, the stones are pushed to the surface, and to a larger extent, the frost heave sorts all fine and larger material too, creating a domed surface! How exciting.

Stones which are on top of this dome then fall down to undomed areas because of gravity. This is typically every 1 to 3 metres. These rows of stones can end up connecting and form polygonal shapes.

On slopes, between 3 and 50 degrees, these polygons become warped and are known as elongated stone polygons, or garlands. On even steeper terrain these become stone stripes.

Blockfields

Lord help me if this comes up in the exam (iam not religious)

Blockfields are believed to be formed as a result of chemical and mechanical weathering below the active layer in periglacial regions such as plateaus or mountain tops, as these are typically glacial fringe regions rather than ice covered areas.

Over time, these processes produce an uneven, angular & bouldery landscape which is only revealed after the permafrost layer melts away, forming ‘in situ’ (alternatively by rock glaciers - which are glaciers containing a large amount of frost-shattered rocks.). Blockfields potentially formed 23 million years ago during the Neogene epoch, when the climate was relatively warmer than today; higher amounts of chemical weathering then initiated the (very slow) process of eroding formed bedrock.

Resistant rock, or tor, may be more prominent in these blockfields as they are not as susceptible to denudation (erosional processes).

On slopes above a gradient of 25o, block streams/stripes are formed as gravitational forces will move this material down a slope.

Types of mass movement

Solifluction lobes

When the ground and soil on slopes is frozen during the winter, the soil particles are separated slightly and loosened by the ice which forms and expands by around 9% between these particles (frost heaving).

During the thawing of the active layer in the spring and summer months, water saturates the ground as it cannot drain easily (due to the impermeable, frozen permafrost below - it is forced to stay in the upper layer) or evaporate due to the cooler climate. Friction is reduced between these particles, which are already loose due after the freezing months, as this water is able to lubricate them. As a result of this excessive lubrication, the soil moves downslope easily. (The extra mass from the water can also help with this.)

Soil/Frost Creep or Mass Wasting

This is a process which moves material down a slope by a few centimetres per year even on high gradients.

On freezing, the particles in the slope’s soil are raised at a 90o angle to the slope (vertically), and when the soil thaws and the particles are dropped, the particles are now at a slightly lower point to their original location. This is then repeated over time

Pingos

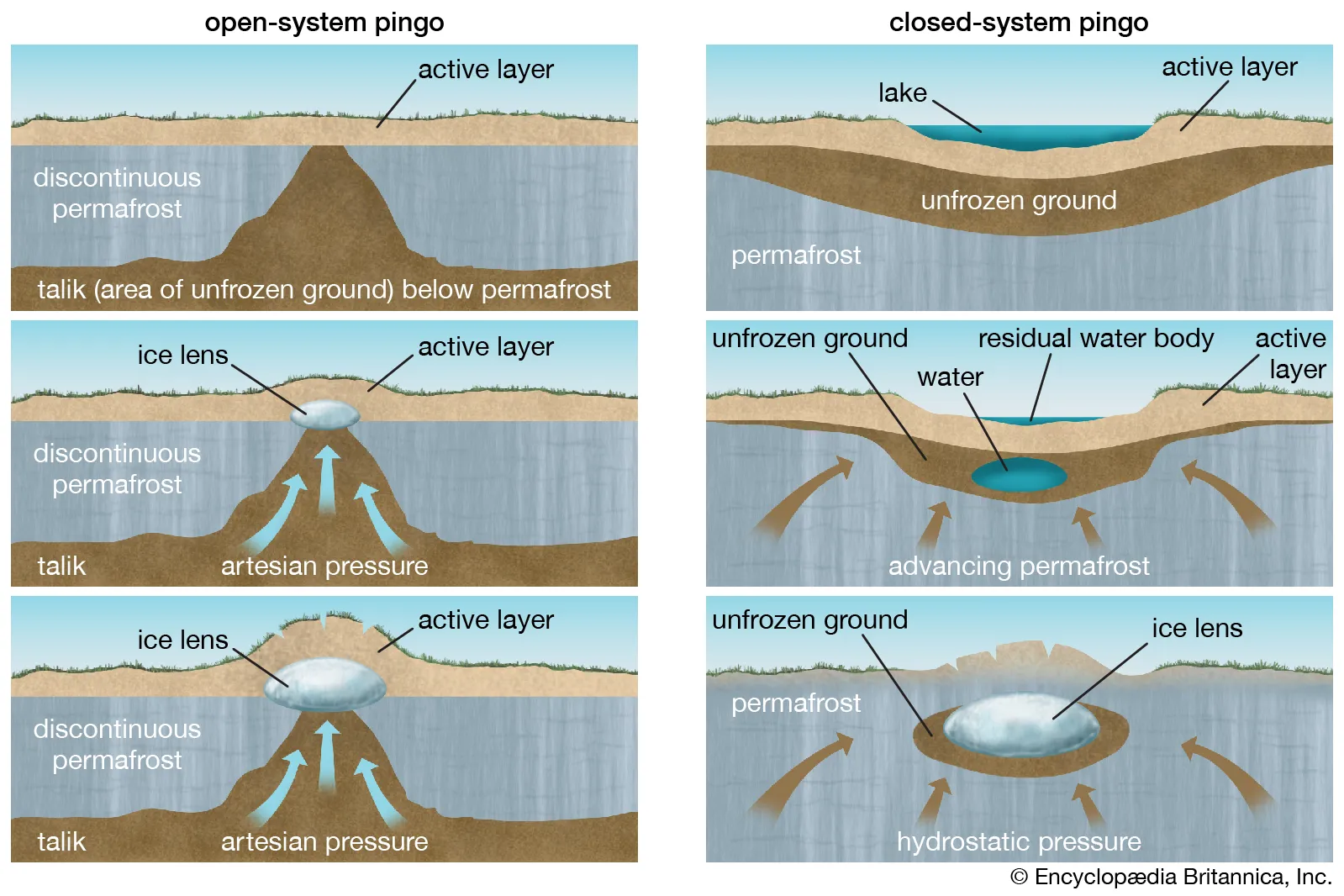

Open system, hydraulic

These are also known as East Greenland type pingos as they commonly occur there.

They form in areas of discontinuous permafrost, typically in the base of valleys. Groundwater collects in the bottom of the valley, and begins to freeze and expand under artesian pressure, creating an ice lens between the active layer and the discontinuous permafrost. This ice lens creates a dome, expanding the ground and active layer upwards.

Closed system, hydrostatic

These are also known as MacKensie type pingos.

These pingos develop below lakes, due to the immediate water supply. Lake water enters the talik as it is trapped between the frozen surface above and permafrost advancing during cooler periods. The talik becomes saturated quickly and hydrostatic pressure compresses this as much as possible, forcing out any warmer air bubbles. Due to the persistence of permafrost, it forces this saturated talik to freeze, becoming an ice lens, and expanding upwards into the familiar dome we know, love and recognise as a pingo.

Bonus! The ice lens can collapse and leave a depression, typically a marshy area called an ognip, surrounded by ramparts.

Ice-wedge polygons

Soil cracks when cooled quickly, just like how mud cracks when dried.

In summer, this crack in the soil fills with meltwater. Over time as many freeze-thaw cycles occur, the ice is expanded by 9% each time. This eventually results in the formation of an ice wedge. Each time the water is refrozen into ice, pressure against the surrounding soil increases, causing it to be pushed upwards, contributing to the development of these polygon features.

Human activities in Glacial and Periglacial Landscape Systems

Key Ideas

4.a. Human activity causes change within periglacial landscape systems.

4.b. Human activity causes change within glaciated landscape systems.

Case study: Oil extraction in Alaska (Periglacial)

Part of Alaska is located within the arctic circle, at 66.5oN.

However, since 1968, vast amounts of oil reserves have been found offshore and within Alaska itself, including inside the ANWR (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) and, more specifically, Area 1002 within it. An estimated 12 billion barrels of oil is located in this area alone, with half of it (~6bn) being available to extract using currently available techniques.

For the United States, this would provide a key resource for energy security, while at the same time reducing dependence on foreign, potentially malicious, entities, which may limit their supply, such as Russia. This weakness has been seen in Europe, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, so now more than ever the US sees this as essential.

It imported 37% of its total oil consumption in 2016 (7,259,000 barrels per day).

Hydrological processes

Gravel extraction adds insult to injury. The loss of gravel from fluvial systems can change the composition of the river profile and exacerbate damages further downstream from the extraction site. Extracting gravel from a glacial outwash site has been proven to lower the groundwater levels by over a metre in a 2km radius as well.

Urban heat island effect

Barrow, Alaska is the northernmost settlement in the USA and the largest native community in the Arctic, with a population of 4600 in 2000, increasing from just 300 in 1900. Recent decades have seen an increase in mean annual and winter air temperature, with an earlier snowmelt in the village and a

weaker snowmelt trend in the surrounding tundra.

The urban heat island (UHI) effect is a phenomenon where urban areas are significantly warmer than their rural surroundings due to activities by humans, like air conditioning, hot water pipes and road building.

A strong urban heat island (UHI) was found during winter, with the urban area averaging 2.2 °C warmer than the hinterland. There was a strong positive correlation between monthly UHI magnitude and natural gas production/use, ultimately resulting in a 9% reduction in accumulated freezing degree days in the urban area.

This excess heat is mostly generated from:

- The burning of fossil fuels during flaring. This increases the carbon dioxide concentration in the local atmosphere, resulting in an enhanced greenhouse effect. This increases amounts of terrestrial radiation within these areas.

- The absorption of solar radiation by urban surfaces - solar insulation warms up these more than surroundings as tarmac/gravel structures are black, which absorb more radiation.

- The reduced evaporative cooling from vegetation.

As a result of this input imbalance, permafrost can thaw, leading to changes in the landscape and the release of trapped carbon dioxide and methane, which can further contribute to climatic changes in these areas locally, as well as internationally, as permafrost contains 1.5 trillion metric tons of carbon (that’s 1,500 petagrams if you’re fancy like that - or double than what’s in the atmosphere today).

This thawing can furthermore lead to infrastructure damage, as roads and buildings can be damaged by the shifting of the ground due to solifluction.

Thermokarst

A landscape characterised by depressions due to the thawing of the ground ice which comprises the active layer and permafrost below. Visible in the Atlaskan North Slope.

Case study: Kárahnúkar HEP Dam, Iceland

This dam (or, collection of three dams) were built in East Iceland on a large proglacial lake, sourced from one of the largest glaciers in Europe. It is actively retreating, so provides water to the dam which can then be used as hydroelectricity. The dam itself was finished in 2007 and is large enough to be seen from space.

The dam could provide enough energy for all Icelandic homes and small businesses, but instead all energy provides the nearby aluminium smelter called Alcoa.

However, there has been widespread backlash over the prokect, as it flooded over 400,000 acres of unspoilt highland wilderness which was the second largest unspoiled area in Europe. In total, almost 750,000 acres of land was affected by the construction of the dam, which is around 3% of Iceland’s total land mass.

The dam was built as Alcoa produces 2% of the world’s aluminium supply, and global financial markets at the time of construction were expected to make a significant number of jobs, and this aluminium industry was expected to make up 10% of Iceland’s total GDP. This has not happened yet, and the price of aluminium had almost halved just two years after construction finished, and has not recovered to this level seldom for market bubbles seen with the Russian invasion, which stressed productions of almost all raw materials.

Glacial meltwater, or milk, is released by the Vatnajökull glacier and flows into the lake blocked by the dam. This glacial meltwater is known to have high concentration of sediment within it, and as such reduces the capacity of the dam over time. This is because the suspended sediment at the base of the water solidifies when deposited, as there is little kinetic energy at the bottom to keep suspended sediment floating. Over time, the base level of the lake increases, reducing overall water capacity, until this excess sediment is ‘purged’ by the dam management system, which may happen annually.

Here’s a video of sediment getting purged

That’s the end for glaciation! I hope you found it useful.

What if I told you about Paraglaciation and Paraperiglaciation as well?

[TBD] Disease Dilemmas

This will take a while to write up…

NEA stuff

Spearman’s Rank

In the first sheet, in cell E5, you write:

=RANK.AVG(C5,$C$5:$C$24,0)

This compares the value of the cell in C5 to those in cells 5 to 24.

You then go to the bottom right of the cell and drag the dot to cell E24

This will copy that earlier formula to give the results for each row. This is because we need the results in an ordered format.

Repeat this for the Cancer rate column (so =RANK.AVG(D5,$D$5:$D$24,0)) in column F

Finally, in any other cell, we can use the cool excel CORREL function to just work it out

=CORREL(E5:E24,F5:F24)

This gets the spearman’s correlation for the two sets of data

Footnotes

(Disclaimer) AI-assisted writing

ChatGPT or any other text-based generative transformer model was not used to directly write the content here. It’s good for clarification of certain topics (and I’ve used it for that), but don’t get used to it otherwise you’ll lose your creativity.

Extra Info

Roche moutonées in english

Just kidding, I spent like 10mins reading it in French but here’s the English version haha: https://gq.mines.gouv.qc.ca/lexique-stratigraphique/quaternaire/roche-moutonnee_en/