< Back to A Level Cheat Sheets

A Level OCR Geography: Complete Cheat Sheet

⚠ This is a work-in-progress, unfinished document. The most unfinished sections are marked with [tbd] and there may be general issues and typos. ⚠

please let me know if there are any errors :)

Latest update: 02/06/2024 22:33

Last content addition: 02/06/2024 22:33

License: CC BY-NC 4.0 - you may use this in your own work, but a link to this resourse and author acknowledgement must be given. please click the link for the full legal deed.

You can use a PC/device with a wide screen to see the Table of Contents and quickly navigate through this document.

Discuss with other students, developers, educators and professionals in the Baguette Brigaders Discord server! You can also receive a notification when there are new Cheat Sheets, Summary Sheets (new!) or other revision material is made public there!

NEW! You can also follow iBaguette on Instagram for updates and new Cheat Sheets, study memes and clips, revision tips, and more!

Top-notch graphic design by me

Let’s get right into the content!

Paper 1 - Physical Systems

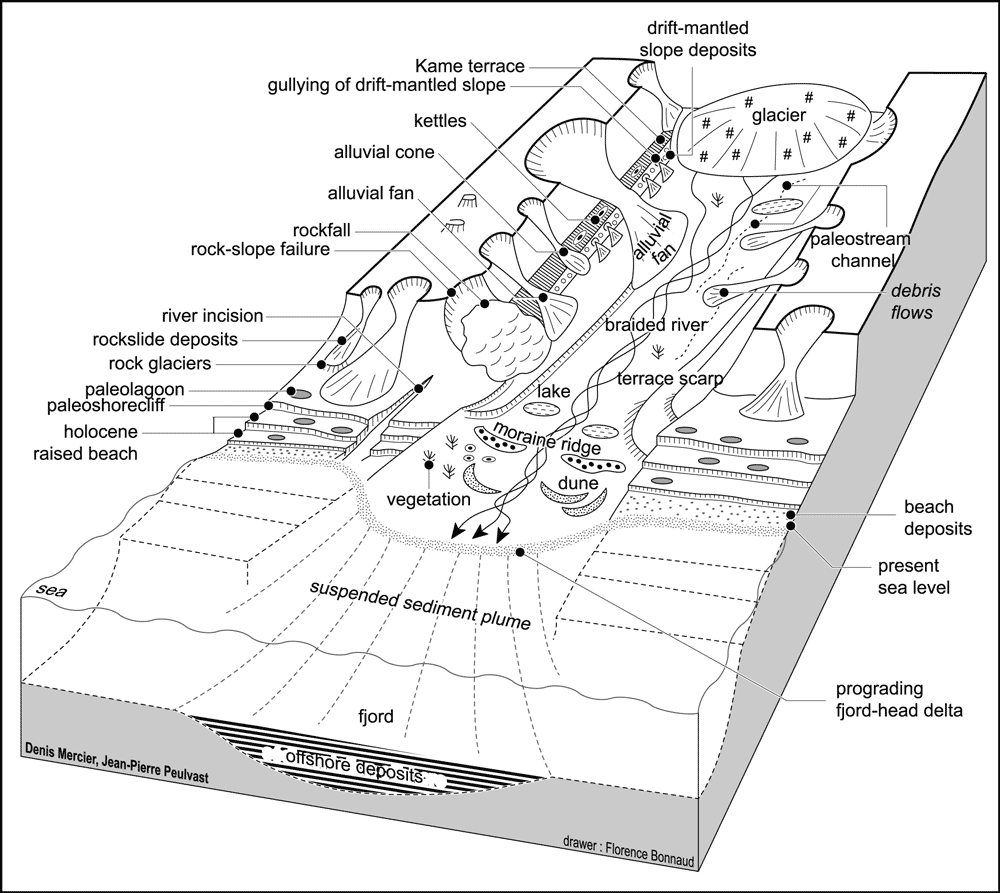

1.1 Option B – Glaciated Landscapes

“Feeling a little like a drumlin today.”

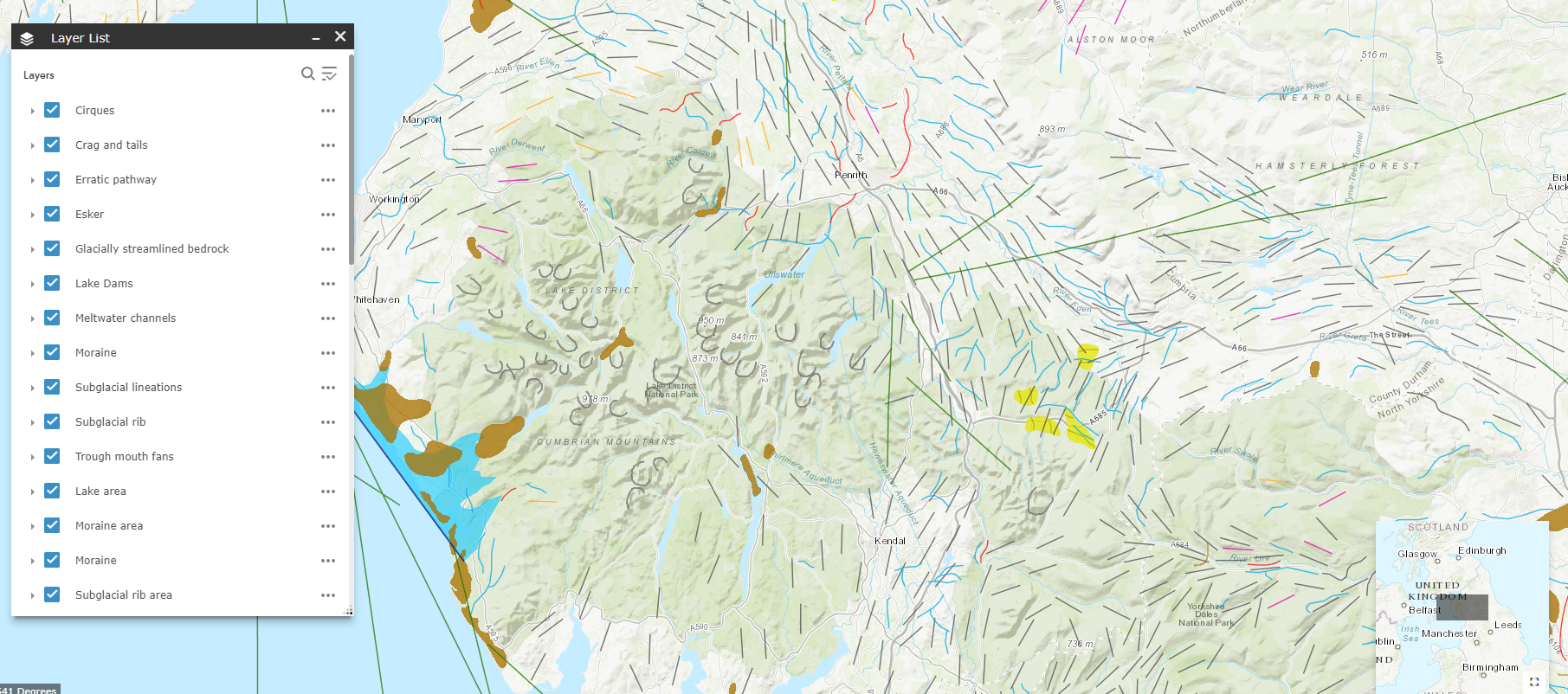

Check out this interactive ARCGIS British ice map to see places in the UK which have been influenced by glacial activity, with drumlins, subglacial lineations, moraines and more!

Glaciers as Systems

1.a. Glaciated landscapes can be viewed as systems.

Valley glacier photo by Simon Fitall

There are 3 main parts to any system: inputs, processes and outputs.

Glaciers are dynamic. Glaciated landscapes may be seen as a system with many interrelated components (stores), processes (cause/effect mechanisms), inputs and outputs. This forms an open system.

- Inputs

- precipitation (snowfall)

- material from deposition, weathering and mass movement

- avalanches

- thermal energy (from the sun)

- kinetic energy

- Outputs (Ablation)

- evaporation

- sublimation

- wind erosion

- meltwater

- Stores

- ice

- water

- debris

- potential energy (from its location)

- Throughputs/processes

- debris movement downslope

- deposition

- kinetic energy from glacier movement

Glaciers themselves can be seen as systems as they have a TON of different inputs, outputs, flows (or transfers) and stores.

Useful key terms

- Terminus - the end of a glacier

- Snout - the end area of a glacier

- Ablation - melting

- Calving - when chunks of a glacier terminus fall into water

- Advance - when a glacier is moving forwards; gaining mass balance

- Recession - when a glacier is retreating; losing mass balance

- Area of accumulation - the area of a glacier where it is gaining mass

- Area of ablation/wastage - the area of a glacier where it loses mass

- Névé - young, granular snow

- Firn - névé which has survived a full season (year) of ablation and is partially compacted, and has been recrystallised into a substance denser than névé, an intermediate stage to becoming glacial ice.

- Firn line/equilibrium line - the zone on a glacier where accumulation is equal to ablation over a 1-year period

- Sintering - continued fusion and removal of air as a result of compression by the continued accumulation of snow and ice

- Aspect - the direction that a slope faces.

- Azimuth - the compass direction of an object

The Glacial Budget and Mass Balance

A glacier forms when snowfall exceeds summer melt in an area, resulting in the accumulation of snow and ice year after year, typically in a hollow on a mountain with a northwest-southeast aspect in the northern hemisphere.

Over time, snow is compacted and turned into glacial ice, and when this is around 40m thick, the intense pressure causes it to begin flowing. The top of the glacier is white, but glacial ice at the base of the glacier is blue as oxygen has left the system.

Snowflakes -> Granular snow -> Névé -> Firn -> Glacial ice

Glacial ice has a density of 850kg/m3. It is rock hard, feels glassy and is almost translucent.

The glacier mass balance is the total sum of all the accumulation (snow, ice, freezing rain) and melt or ice loss (from calving icebergs, melting, sublimation) across the entire glacier, or amount of ablation.

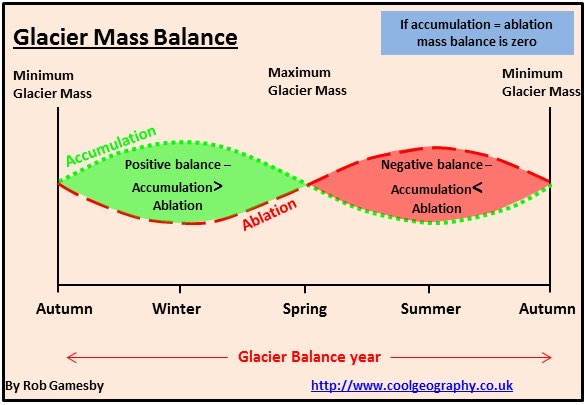

Over a year, the graph of mass balance in a northern hemisphere glacier may look like this in a typical scenario:

An equilibrium is reached between accumulation and amlation are equal. This point may be reached between the accumulation extreme in winter and the ablation extreme in the summer season. In the image above, as the accumulation is equal to ablation, the glacier is not growing.

Layers of snow within the ice give evidence of the way that it has formed.

ysical factors affecting landscapes

1.b. Glaciated landscapes are influenced by a range of physical factors.

Regional climate

The wind is a moving force and can carry out processes such as transportation, position and erosion. In the air, these are known as aeolian processes, and can contribute to shaping glaciated landscapes. It is more effective when acting upon fine materials, usually those previously deposited by ice or meltwater, such as smaller rocks, dirt and sand.

Temperature within the climate is another factor, as temperatures above 0°C will melt accumulated snow and ice, resulting in more outputs in the system. At highTypes of glacier and movement

(Date studied: ~29/09/2022)

An ice sheet is a mass of snow and ice, greater than 50,000km2 with considerable thickness.

A piedmont glacier spreads out as a wide lobe as it enters altitudes, there are typically more prolonged periods of above-freezing temperatures, and melting, compared to in high latitude locations, where is below freezing most of the time, allowing for glaciers to thicken and expansive ice sheets to form. Precipitation is another climate factor, with its totals and patterns, both region wider plain typically from a smaller valley

A valley glacier is one **bound by valley and seasonally, in determining the mass balance of a glacier system, as it provides the main inputs to these glaciers as snowfall.

er aally rate s aLatitude and Altitude

Beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, located at 66.5° north and south, the climate is very dry, with little seasonal variation. Being so dry and extremely cold, they are much different to more dynamic valley glaciers as they have higher precipitation levels, and more névé turns into firn. The dryness contributes to periglacial environments (see below for more about those!) while also turning the types of glaciers in these areas to more cold-based. This means that they flow much less quickly, and different types of movement occur.

Altitude also has a direct impact on the temperatures and development of valley glaciers. As temperatures typically decrease by 0.7oC every 100m of altitude gained, there are more likely to be valley glaciers in areas of high relief, as seen in the Alps and the Himalayas. These glaciers are still not as cold as cold-based glaciers, however.

Geology

Geology is more than just “weak” and “strong” rocks and resistance. It is a combination of properties that uniquely determine how rocks react to stress, mechanical and chemical forces, and the environnment.

Lithology is the chemical composition and physical properties of rocks. Some types, like basalt, are very resistant to erosion and weathering, as they are comprised of densely packed interlocking crystals. Clay, on the other hand, is weak and does not have these strong bonds on the molecular level. The solubility of rocks like chalk can also be affected by acidity, making them prone to chemical weathering, as seen through carbonation. Weakly-bonded rocks also reduce their resistance to glacial erosion.

Structure relates to the physical rock types, like faulting, bedding and jointing. These all have an impact on how permeable rocks are. Chalk, for example, is very porous, spaces between the particles within it on the molecular level allow water to percolate through. In glaciated environments, this is significant as freeze-thaw action can crack rocks with faults or pores from the inside. This compares to crystalline rocks such as igneous granite which do not have any of these structural weaknesses.

Some types of limestone, like carboniferous limestone, have many interconnected joints, giving it ‘secondary permeability’.

Primary permeability is when spaces (pores) absorb and retain water.

Relief and aspect

These have an impact on the the microclimate. This is a small region with its own distinct climatic chawalls**, coming from a higher mountain region, from a plateau on an ice cap or an ice sheet.

An ice cap is a dome-shaped mass of glacial ice usually situated on a highland area and also covers >50,000km2.

Valley glaciers usually occur in high altitude locations, with high relief, have fast rates of flow at 20–200m/year (mostly warm-based) and have distinct areas of ablation and accumulation, descending from mountains.

Ice sheets, however, are large masses of snow and ice defined by being greater than 50,000 km² and are usually in locations of high/low latitude and have slow racteristics, for example, one side of a mountain, or the north side of a valley. Generally, wider climate characteristics play a larger role in influencing the behaviour of glaciers, but glaciers are also affected by various lower-level and smaller-scale conditions.

Areas of high relief mean there is greater gravitational potential energy for faster glacial movement.

Types of glacier and movement

1.c. There are different types of glacier and glacier movement.

An **ice sheet is a mass o so ice reater ha , it nsderae thine imnt acr spres out s a ie loe s it eter aider a typically frm a maller le all glacier is one ond b ally all, ming frm a ihe mnin egir a lateauon an ice ca or an ie sheetn ie cs of movement and only around 5m/year (mostly cold-based). The base of the glacier is frozen to the bedrock and has a little precipitation but also lower temperatures so adomeshaped ms of glacial ie usaly sitated n a hhland re nd also coers mblation levels are lower too.

Fundamentally, glaciers move because of gravity. The gradient influences the effect of gravity on glaciers. The thickness of the ice and the pressure exerted on the bedrock can also influence melting and movement. More accumulation also leads to more movement. When ice is solid and rigid, it breaks into crevasses (big cracks in icegaps visible from the surface). Under pressure, ice will deform and behave like plastic (zone of Plastic Flow on the lower half of the glacier) making it move faster. Conversely, the rigid zone is on the top half of the glacier.

Valley glaciers usally or altitude ain, th high relief, hae as rates o lo at ear mostly warmae and hve istict ares of blation and accumulation, descending from mountains.

Ice sheets, however, are large msss f snow and ice ine in grate than km n are say inoctins o il latite and have slow rates o moement and ly aroun ear ostl coldased. he ase of te glacie s froen he edroc and has a ittle pecipitation bu also oer temperates so alaton l are loer .

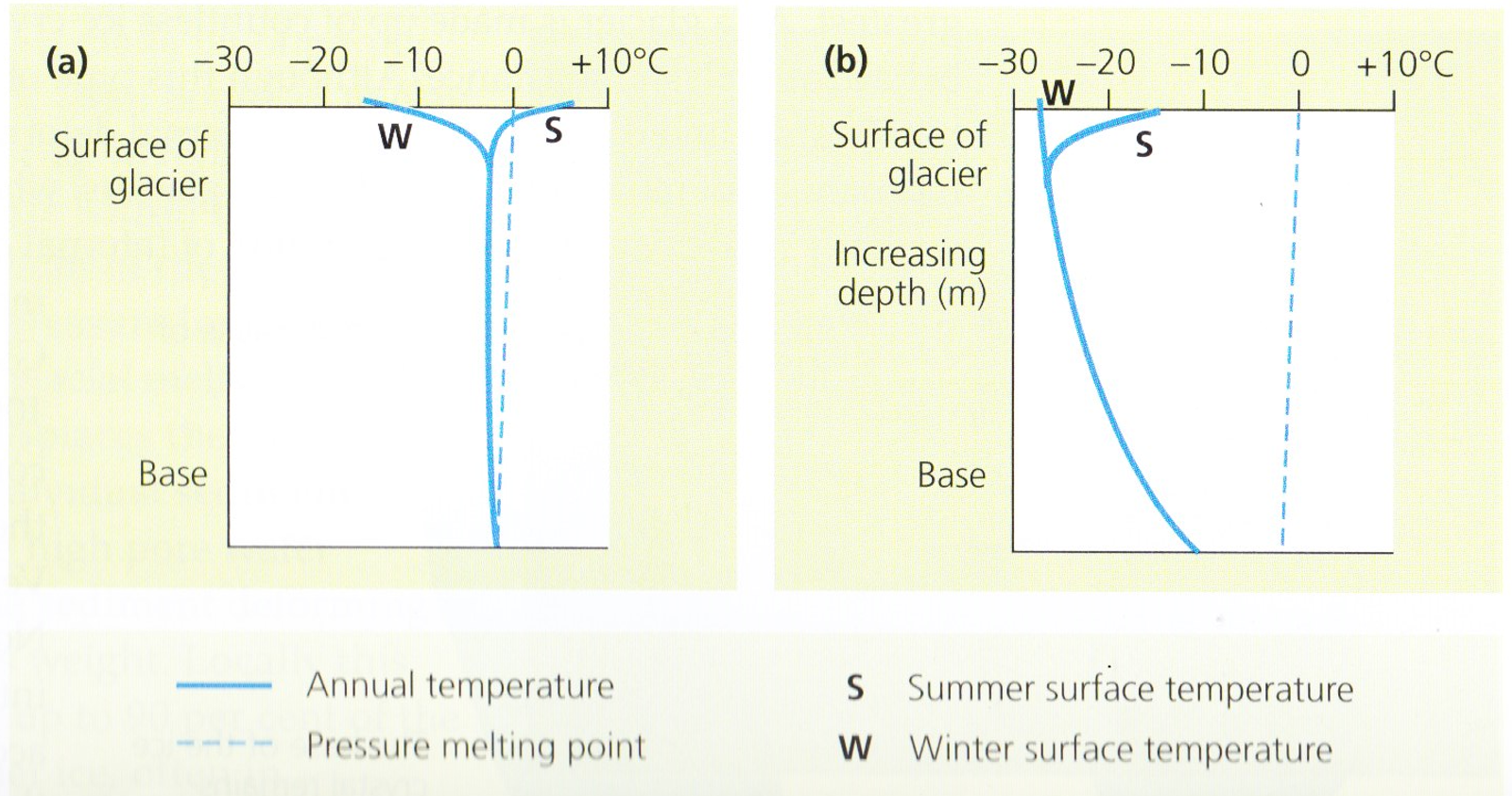

Cold-based (polar) glaciers:

- have a slow rate of movement (<5m/year);

- are located in extreme latitude (polar) regions;

- are generally flat;

- have a low basal temperature, remaining stuck to the bedrock below the pressure melting point;

- are formed in low precipitation areas, and the glacier remains below freezing point during all seasons.

Warm-based (alpine) glaciers:

- have rapid movement (20-200m/year);

- are located in high-altitude (mountainous) regions;

- have a basal temperature at or above the pressure melting point;

- are in areas of steep(er) relief;

- have water present throughout, with the ice acting as a lubricant.

Cold-based glaciers are unable to move by basal sliding as the basal temperature is below the pressure melting point. Instead, they move through internal deformation.

Ice at 0°C deforms 100 times faster than at -20°C. Thus, the movement within cold-based glaciers is limited by there being a lack of lubricant, and the cold temperatures inhibiting internal deformation to a very slow rate.

Factors affecting the microclimate

The microclimate is a small region with its own distinct climatic characteristics, for example, one side of a mountain, or the north side of a valley. Generally, wider climate characteristics play a larger role in influencing the behaviour of glaciers, but glaciers are also affected by various lower-level and smaller-scale conditions.

Regional climate

The wind is a moving force and can carry out processes such as transportation, position and erosion. In the air, these are known as aeolian processes, and can contribute to shaping glaciated landscapes. It is more effective when acting upon fine materials, usually those previously deposited by ice or meltwater, such as smaller rocks, dirt and sand.

Temperature within the climate is another factor, as temperatures above 0°C will melt accumulated snow and ice, resulting in more outputs in the system. At higher altitudes, there are typically more prolonged periods of above-freezing temperatures, and melting, compared to in high latitude locations, where is below freezing most of the time, allowing for glaciers to thicken and expansive ice sheets to form. Precipitation is another climate factor, with its totals and patterns, both regionally and seasonally, in determining the mass balance of a glacier system, as it provides the main inputs to these glaciers as snowfall.

Geology

Lithology is the chemical composition and physical properties of rocks. Some types, like basalt, are very resistant to erosion and weathering, as they are comprised of densely packed interlocking crystals. Clay, on the other hand, is weak and does not have these strong bonds on the molecular level. The solubility of rocks like chalk can also be affected by acidity, making them prone to chemical weathering as seen, through carbonation.

Structure relates to the physical rock types, like faulting, bedding and jointing. These all have an impact on how permeable rocks are. Chalk, for example, is very porous, spaces between the particles within it on the molecular level allow water to percolate through. Some types of limestone, like carboniferous limestone, have many interconnected joints, giving it ‘secondary permeability’.

Primary permeability is when spaces (pores) absorb and retain water.

Latitude and Altitude

Beyond the Arctic and Antarctic circles, located at 66.5° north and south, the climate is very dry, with little seasonal variation. Being so dry and extremely cold, they are much different to more dynamic valley glaciers as they have higher precipitation levels, and more névé turns into firn. The dryness contributes to periglacial environments (see below for more about those!) while also turning the types of glaciers in these areas to more cold-based. This means that they flow much less quickly, and different types of movement occur.

Altitude also has a direct impact on the temperatures and development of valley glaciers. As temperatures typically decrease by 0.7oC every 100m of altitude gained, there are more likely to be valley glaciers in areas of high relief, as seen in the Alps and the Himalayas. These glaciers are still not as cold as cold-based glaciers, however.

How are lacial landscapes developed?

Glacial landforms are typically classified according to erosional and depositional processes. This development can be described as a series of interrelated processes.

Glacial erosional landforms

Corries

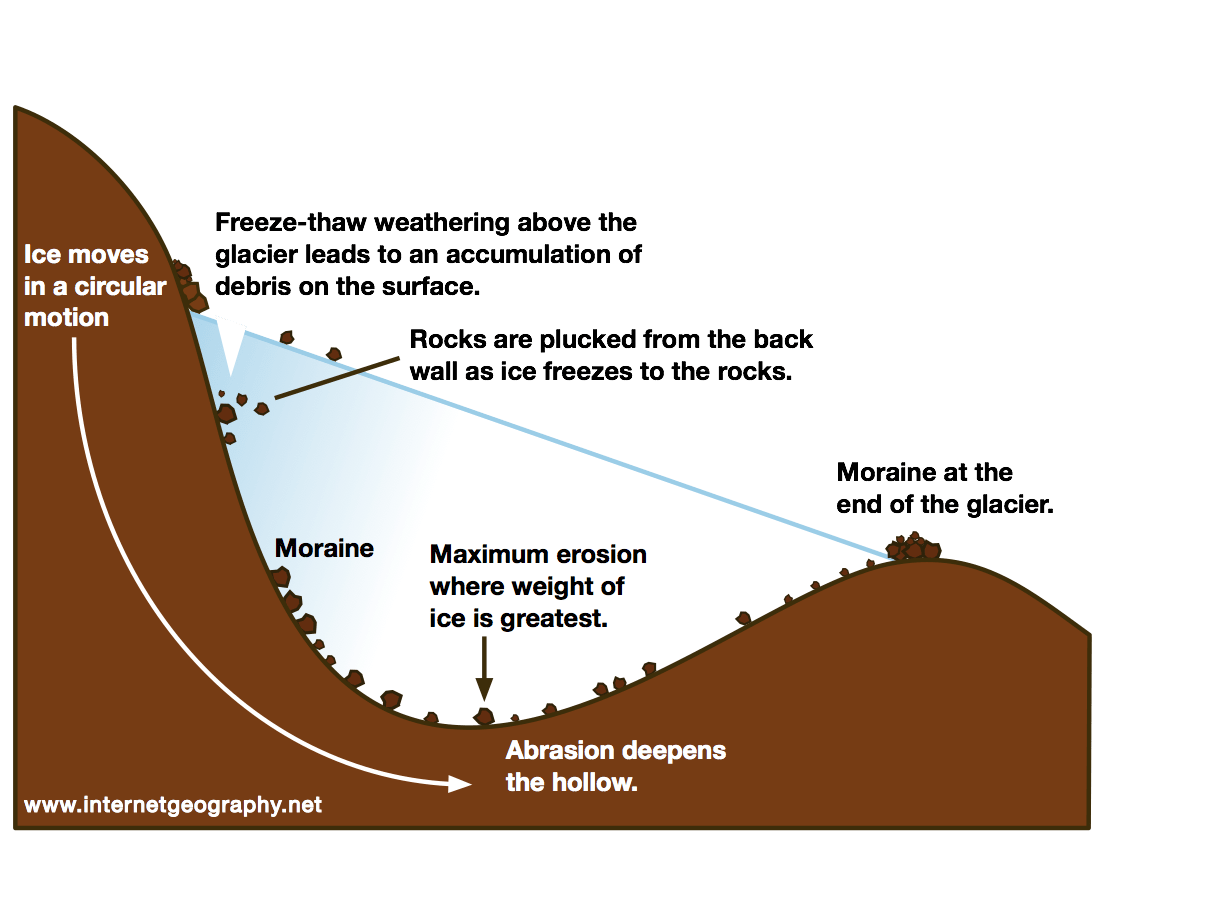

The processes occurring in a corrie.

A corrie is an armchair-shaped depression in a mountain. Also known as a cwm or cirque, they are formed from small hollows on the slopes of mountains where snow begins to accumulate, typically on the north-west to south-east facing slopes (or with an azimuth ranging from 300-140 degrees) on a mountain in the northern hemisphere.

This is due to its aspect, or the orientation of which a slope faces, with this specific aspect resulting in having less insolation. Greater amounts of irradiation add thermal energy to the system, resulting in ablation.

This virgin snow is known as névé, which becomes firn after one complete cycle without melting (i.e. surviving a summer ablation period; of 1 year).

This newly-formed hollow, deepened by nivation (e.g. freeze-thaw processes) from te ice, then begins to move because of gravity acting upon the ice mass. The ice freezes to the back wall, plucking material (debris), which is then washed out through a process known as rotational slipping. Over multiple years, the snow at the bottom is compressed into ice, and the material plucked or that has fallen into the bergschrund crevasse is used by the ice to abrade and further deepen the hollow. Comparatively, the ice at the front of the corrie may be much thinner and therefore has lower pressure and is less abrasive, creating a rock lip, supplemented by washed out moraine from previously plucked material.

When this ice melts or the area is deglaciated, a tarn (or corrie lake) is created, enclosed by the rock lip. Material may then continue to fall down from the back wall due to continued weathering, combined with aspect and steep relief, known as scree.

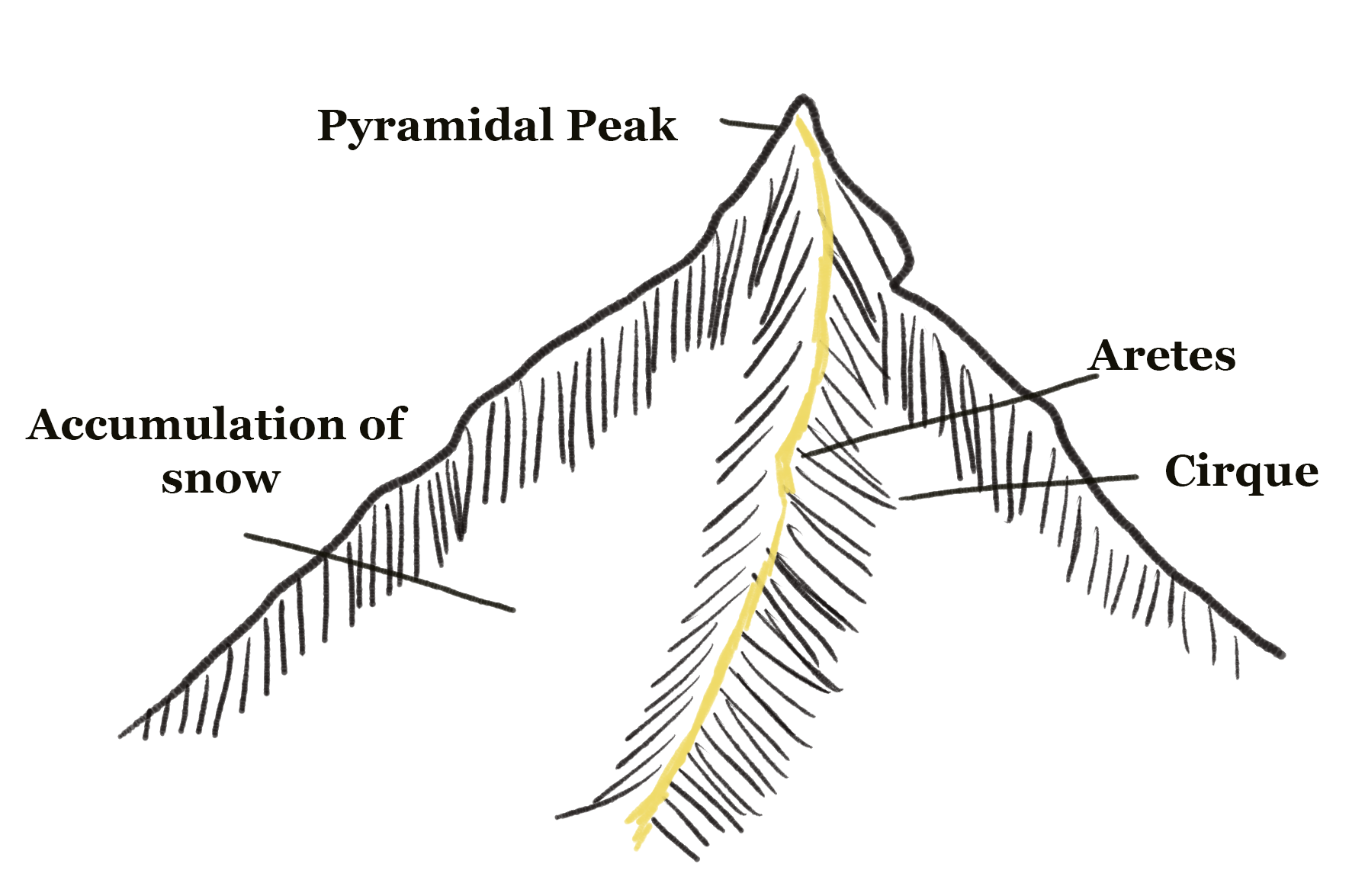

Arêtes

An arête is a knife-shaped, narrow ridge formed when two corries’ back walls continually erode back-to-back. Over time, these back walls meet, and a distinct ridge is formed.

A diagram of a mountain, which has had erosional processes acting upon it.

Pyramidal peaks

A pyramidal peak is a high mountain whose surroundings have been eroded as corries. Three or more corries eroding back-to-back (similarly to how arêtes form) result in this sharp peak forming. There are typically distinct aretes visible all the way up to the peak, representing the boundary between corries.

The Matterhorn in the European Alps. It is a great example of a pyramidal peak.

U-shaped valleys

Also known as a glacial trough, a U-shaped valley is formed as a result of strongly channelled ice, bulldozing its way through a valley. On the valley’s sides, plucking occurs, causine sides to steepen. This rocky material is then dragged by the glacier helping it to carve out more of the landscape.

The actual shape of most U-shaped valleys is parabolic.

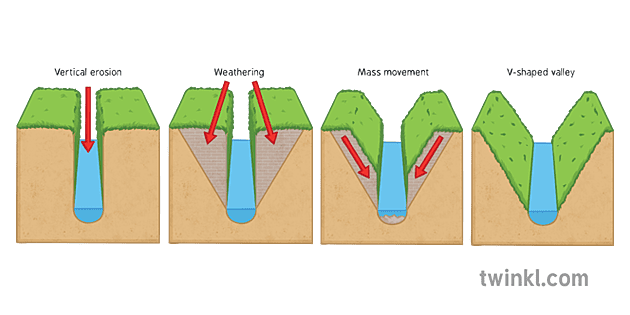

Firstly, before a glacial period, a V-shaped valley exists, having moderately steep sides and a central river channel, with interlocking spurs being a distinct feature. During periods of glaciation, snow begins to accumulate in these valleys as they are often sheltered.

How a V-shaped valley is formed. Remember this from GCSE? (if not, recap yourself on the GCSE cheat sheet!

When an ice mass has formed in the valley or flowed from an upland area, freeze-thaw weathering begins to occur above the glacier line (where this ice mass is), causing the valley to steepen, in the same way as a corrie steepens its back wall. The glacier itself also causes plucking, mostly on the sides, as rocks are frozen and ripped as the glacier moves. Vertical abrasion also deepens the valley floor as subglacial material comes into contact with the bedrock.

Hanging valley

Hanging valleys with waterfalls and truncated spurs are a feature of the U-shaped alley landform. They are visible within this glacial trough, and form as a smaller glacier from another valley has created a U-shaped valley which then enters the larger valley. As the hanging alley’s lacier is smaller, it is less powerful, so it does not reach the base of the larger glacial trough valley.

Photo from Peter Hammer.

Water features

After deglaciation, there may be some (iconic) water features in these glacial troughs.

Ribbon lake

Glaciers ero the valley into the typical U-shape. These lakes are typically long, thin and deep as a result of compressing flow, as this ice is likely to havee from an area of high incline to a more expansive area a the ice is more likely to move faster and pushed into a thinner area downstream, so is more likely to erode vertically rather than laterally. This depression (or rock basin) is then refilled with water after a glacier retreats. More detail over aieted to swatullswattecacvt t td he Li District case study section.

Misfit stream

A ribbon lake well as a misfit stream may also be present in the base of the newly-formed glacial trough valley after deglaciation.

![]()

Misfit stream: Photo from Mario Álvarez.

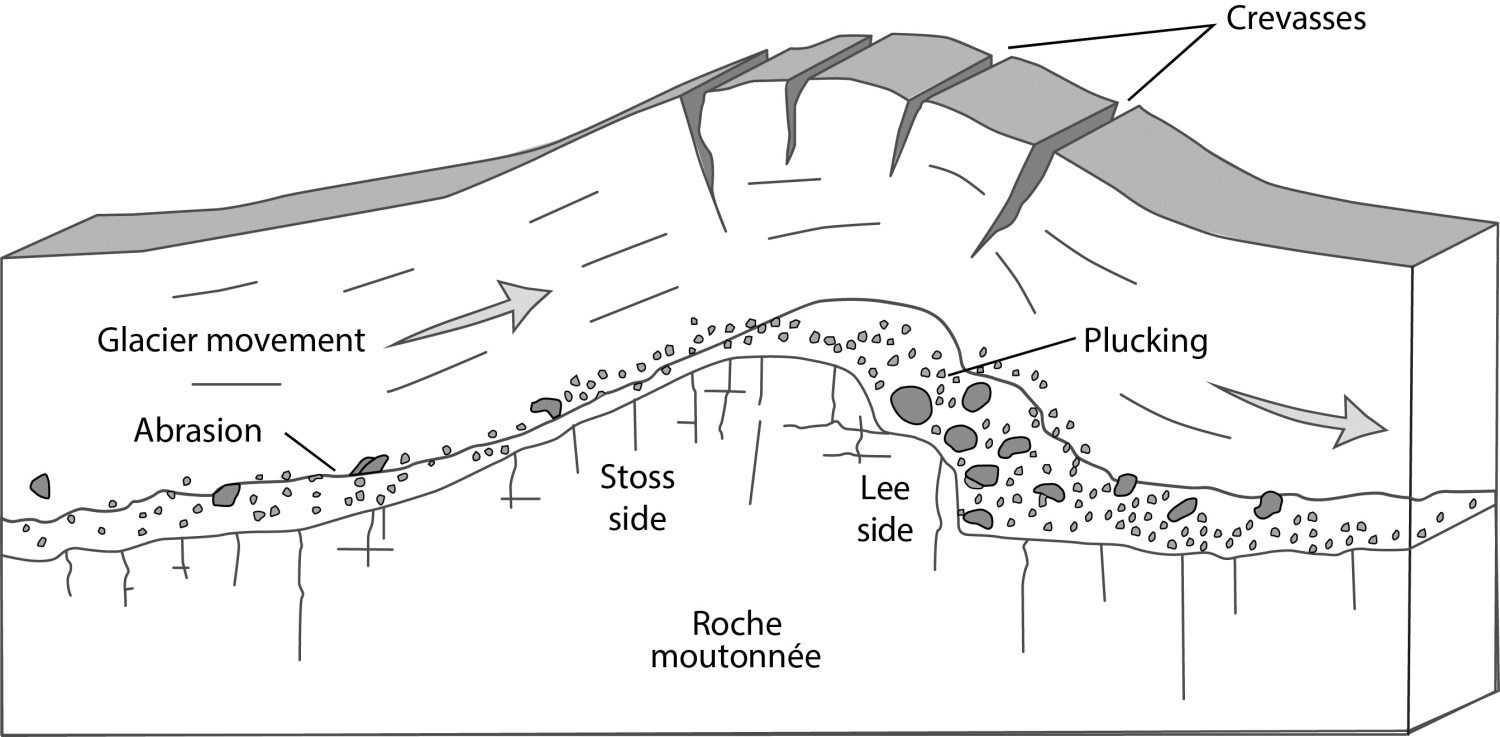

Roche moutonnées

A roche moutonnée is a more rebstant rock in the path of a glacier. Light abrasion from the above subglacial material occurs on the upvalley (stoss) side, resulting in striations, grooves, and polishing from subglacial debris. There may also be pressure melting at a local scale on this side.

As this meltwater is forced up and oer the roche moutonnée, mechanical plucking and freeze-thaw weathering occur. On the down-valley (lee) side, the pressure release results in refreezing into ice, while the glacier continues to move, thereby pulling away the rock and giving it a craggy appearance.

Roche moutonnées are generally concentrated in areas of competent bedrock, such as granitoids (Glasser, 2002) - this essentially means that rocks are somewhat resistant to deformaton.

Source: Québec government website

The word is French with “roche” meaning rock and “moutonée” meaning sheep.

More specifically, it was introduced by a French geologist called Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799). The word is called like so due to its resemblance to the shape of a wig, worn by 18th-century French aristocrats which shaped their hair like a wave. Sheep fat was used to hold the wig in place, which explains the term moutonné (Benn and Evans, 2010). In Sweden, very large roches moutonnées are called flyggbergs, with some being up to 3 km long and 350 m wide (Rudberg, 1954; 1973; Iverson et al., 1995; Benn and Evans, 2010).

Ellipsoidal basins

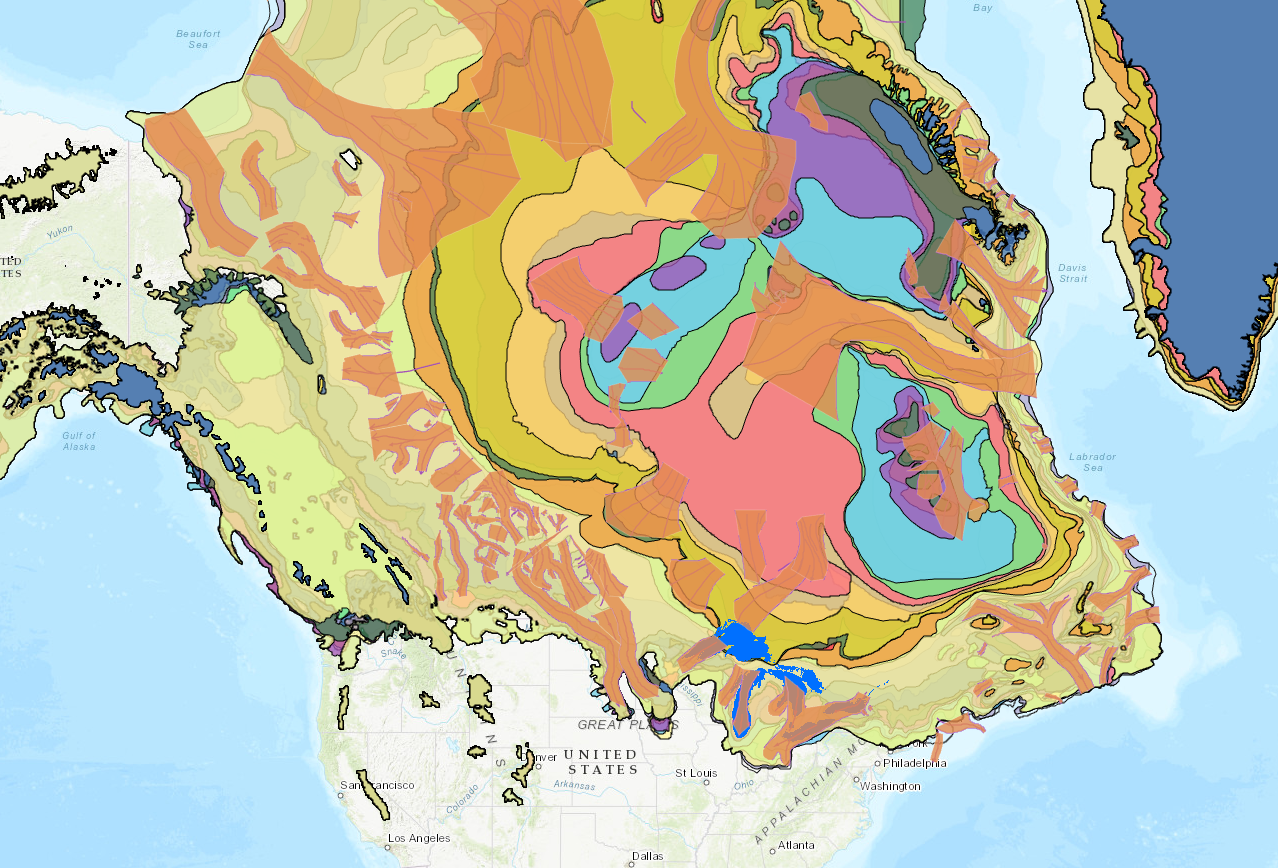

These are no ordinary valley or alpine glacier erosional landform. These are huge areas formed by ice sheets such as the Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America. (more detail with the Minnesota Ice Sheet Case Study)

These huge ice sheets (more than 50,000km2) exert large amounts of pressure on the landscape as well as great erosional quarrying by subglacial material. Examples of this feature include Hudson Bay, and smaller ellipsoidal basins created the Great Lakes in North America.

On top of the subglacial erosion which may have occurred, some of this large-scale erosional landscape’s formation is also due to isostatic lowering. This involves the sheer mass of the ice sheet, potentially several kilometres thick, exerting pressure on the lithosphere and effectively compressing it into being smaller.

After deglaciation, isostatic readjustment may occur, and these compressed, lowered areas may readjust and bounce back upwards, now being under no additional pressure.

Glacial depositional landforms

- Supraglacial material is material which is located on the top of a glacier.

- Englacial material is material which is located inside a glacier.

- Subglacial material is material which is located on the base of a glacier.

- Material deposited during glaciation is called drift.

- Material deposited directly by ice is called till.

- Material deposited by meltwater is called outwash, or glacio-fluvial material.

Lodgement till is material deposited by advancing ice, due to pressure being exerted into existing valley material, and left behind as ice advances, such as the theory of dsepositional drumlins.

Ablation till is material deposited at the terminus by melting ice from stagnant, or retreating glaciers during a warm period or end of glaciation event. Most depositional landforms are this type.

It can be known whether sediment was deposited by water or ice. Ice-transported sediment is angular, not curved, as it has not been subject to more abrasive, erosional forces by the meltwater. The order of size of sediments can indicate this too, as water deposits sediment progressively due to reducing energy levels, while glaciers deposit material unsorted; ‘en masse’. Glaciers also deposit till in mounds and ridges, as, during ablation, this englacial and supraglacial material gets dropped on the bedrock below. This is distinct from the layered deposition (or strata) typically characterised by fluvial processes. Glaciofluvial processes involve an amount of stratification but not complete sorting.

There are a range of depositional landforms visible in this photograph. Can you identify them all?

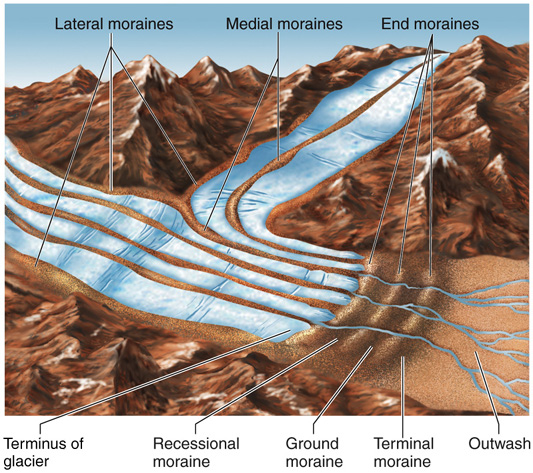

A great diagram of all the different types of moraine.

Moraines

Moraines are ridges of soil, rocks and till which have been deposited by a glacial system. They are added to the glacial system over time through weathering, rockfalls, freeze-thaw action, etc.

Strictly speaking, only the main three are on the OCR specification, but there’s no harm in being able to explain them all.

Medial moraines

Form in the centre of a glacial channel (typically when two glaciers merge - see the image above an o ad you can see how the mountain in the middle is being carved out). Also may occur when their lateral moraines meet and combine into one.

Lateral moraines

Ridges which form on the sides (margins) of a glacial channel, and are the result of the accumulation of debris due to erosional processes on valley sides such as freeze-thaw.

End moraines

These mark a pause or halt of glacial retreat (e.g. when there are a couple of decades with little advance or retreat). These pauses typically are not very long so deposits reflect this, not being too large either (100m max)

Terminal moraine

A ridge, often characterised by bein g the largest and most prominent in the area, marking the maximum advance of a glacial period (glacial maximum), deposited at the snout of the glacier. Often crescent-shaped when observed from the cross profile.

Recessional moraines

A combination of the end and terminal moraines.

Erratics

They are randomly placed bits of rock and other debris which can be characterised by being of different geology compared to that of surrounding rocks, e.g. limestone in a valley mainly of basalt.

This can be seen in the Lake District where rocks belonging to the rock group Borrowdale Volcanics were found in an area dominated by limestone.

The Bowder Stone is another example being a 2,000-ton andesite lava boulder south of Keswick in the Lake District which most likely originated in Scotland.

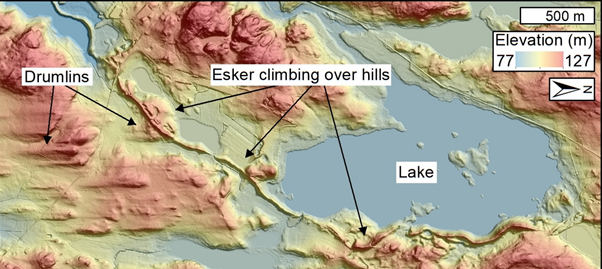

Drumlins

Drumlins are unsorted mounds of streamlined till, commonly elongated parallel to the former direction of ice flow, composed of glacial debris.

It is not known exactly how drumlins are formed, but the most likely and agreed upon explanation for their formation is that the glacier becomes overloaded with till (loses competence), so begins to deposit this sediment due to the increased friction that the till brings (‘smearing’ the landscape). This sediment accumulates and quickly compounds, and other till that flows over the initial bump can become stuck, growing this mound of unsorted till. Over time, this grows, and when the glacier retreats, the distinct hill is revealed. This video is a good example of the theory of depositional drumlin formation.

This is an example of lodgement till (not ablation till) as it is formed as the glacier is still advancing.

Others argue that they may have a bedrock core (hence rock-cored drumlins) and as material was obstructed, sediment began accumulating around this, much like in the way of a dune, and was streamlined in the same way as above.

Another argument to the formation of drumlins is that they occur when a glacier move over an area of existing glacial deposits. As the glacier moves over this existing till, the pressure of the overlying ice causes the till to be remoulded and changed into the characteristic shape of streamlined till that we know and love as a drumlin.

They typically occur in larger groups, or ‘swarms’. This is known as a ‘‘basket of eggs’ topography.

Drumlins can be up to 1,000m in length but are typically around 300-500m. They also improve revenue for farmers, as the topography allows them to have a larger farming area in the same sized plot of land. Their length-to-width ratio is typically between 1.8 and 4.1, and this may be an indication of past glacial velocities, with longer drumlins indicating a faster ice velocity due to the laminar flow of ice.

Drumlins are often found in conjunction with morainic landforms and other depositional features like eskers, kames and outwash plains.

Did you know that the ground between two drumlins is known as a dungeon?

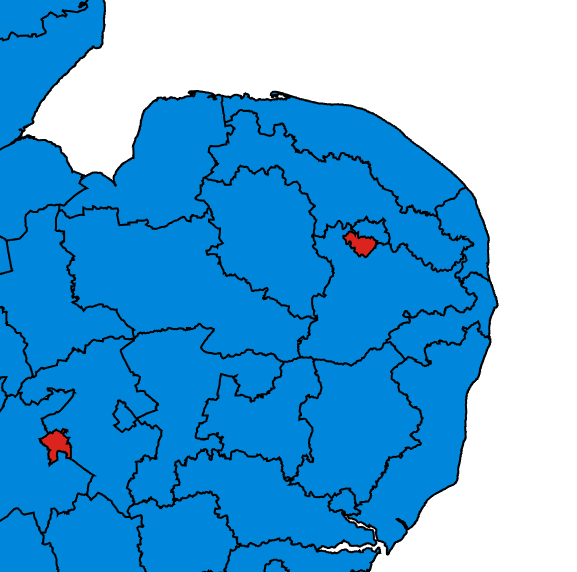

Case study: Lake District

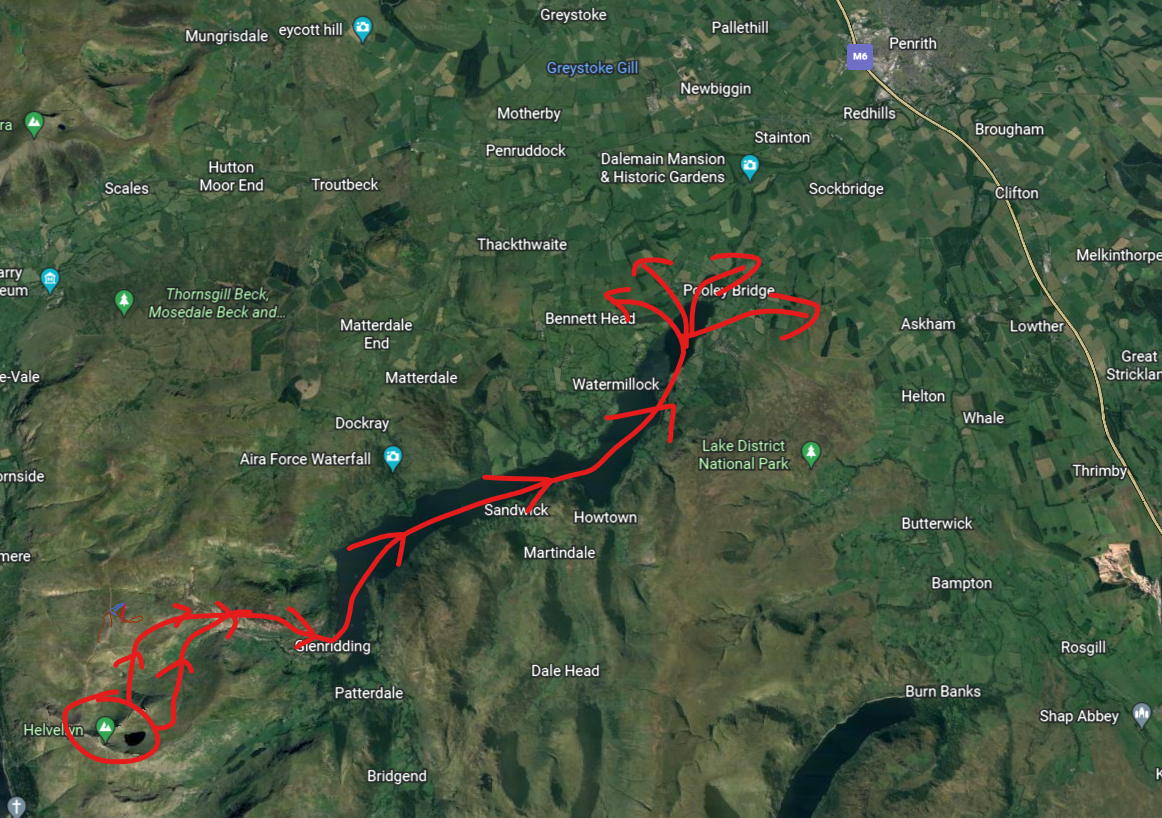

The Lake District is a mountainous area in the north of England. Over the Pleistocene epoch, many glacials and interglacials moulded the area into what it is today, with the most recent activity during the Last Glacial Period (the Loch Lomond Stadial; 12kya) being responsible for the current appearance of the valley landscape.

A beautiful view towards Helvellyn from Blencathra.

A range of physical factors have had an influence on the formation of landforms within the landscape.

Geology

The area has three main geologies:

- Skiddaw Group (or Skiddaw Slates - north; the oldest, sedimentary rocks formed 500mya by compaction and tectonic movement)

- Borrwowdale Volcanics (central; hard igneous rocks formed 450mya including Helvellyn and Scafell Pike (978m) with the largest mountains: it is less prone to erosion)

- Windermere Group (south; softer sedimentary rocks and limestone formed 420mya and have been eroded down)

Glacial features of the Lake District, including subglacial lineations, meltwater channels, eskers, drumlins, moraines, glacially streamlined bedrock and more.

Helvellyn Range

Helvellyn is a 950m tall pseudo-pyramidal peak with aretes named Striding Edge and Swirral Edge separating the corrie from Brown Cove Tarn and Nethermost Cove, respectively. These corries are on the north-east side of the mountain. It’s not quite an official pyramidal peak as it only has these two named corries (but for all intents and purposes…).

Ice from Red Tarn at Helvellyn met with the Brown Cove Tarn ice, creating the Helvellyn Gill hanging valley. Flowing northeast into Glenridding Valley, it joined another larger glacier creating a glacial trough in present-day Ullswater. Likely exacerbated by compressing flow, where the ice mass moves slower, a long, thin, deep ribbon lake formed (as the flow made ice more likely to erode vertically). The varied geology also resulted in extending flow contributing to the ununiformityed nature of the U-shaped valley.

This glacier would have continued flowing north-eastwards, taking eroded material with it, towards modern-day Penrith, which is in a flat area, possibly resulting in the old Ullswater glacier becoming a Piedmont glacier when entering this more expansive, larger valley.

Lake District Landforms

Inside modern-day Ullswater is a series of roche moutonnées such as Norfolk Island and Lingy Holm. The geology of roche moutonnées is characterised by being more resistant than other local rock types, possibly with increased jointing and bedding, resulting in striation lines on the stoss, with the freeze-thaw weathering being visible on the lee side still today on these rock islands.

To the west of Helvellyn is the Thilmere ribbon lake. A series of truncated spurs and hanging valleys are located along this U-shaped valley, moulded by a glacier.

Drumlins made of boudlder clay have been deposited south of Kendal. They are oriented to the south-west visible here, supporting the idea that the ice was moving outwards from the area of higher topography to lower areas.

Langstrath Valley has an example of lateral moraine on the north side of it.

The Glenridding village has visible depositional till extending into Ullswater, visible from satellite imagery, proving that there was once glacial activity in the area.

Essay snippet: inter-related valley landforms

Using a case study, assess the extent to which landforms within a valley glacier are interrelated [16 marks]

Plan

- Formation of corries, aretes and pyramidal peaks: Helvellyn, Red Tarn and Nethermost Cove. Overdeepening caused by nivation, plucking on the back wall, and rotational slip causing the armchair shape - only possible because each are interrelated.

- Back to back erosion w/Nethermost Cove: striding edge arete

- Ice flowing from Red Tarn into Glenridding valley creating Helvellyn Gill and joining with another larger glacier - Ullswater, geologies creating roche moutonnées and deepening of lake. Material from erosion upvalley deposited as sediment visible in the lake today

- Erratics may appear to be not interrelated but from erosion - partly related. Longer distances. Till also forms drumlins typically in flatter areas further away - lodgement till

- Overall, undeniable evidence that all landforms are interrelated through the linked processes of erosion and deposition - with erosion acting as the prerequisite for subsequent transport and deposition.

Essay (note: to rewrite!)

A corrie, or cirque, is formed by snow falling and compacting in a hollow over many winters, typically on the northern side of mountains in the northern hemisphere due to the sheltered aspect, and cooler microclimate. Over time, snow accumulates, compacting the snow beneath it into ice due to the air inside being displaced. The back wall of the mountain, for example, Helvellyn in the Lake District, gets increasingly steep due to persistent freeze-thaw weathering and plucking of material, which then gets entered into the young glacier system as englacial material, or lands on the surface as supraglacial material.

At the same time, under its own weight, the ice at the base begins to rotate, known as rotational slipping, deepening the base through abrasion, with this abrasive material being finer sub-glacial debris. At Helvellyn, the bedrock type is known as the Borrowdale Volcanics, having formed 450 million years ago and moved from tectonic forces. Despite this relative strength due to its more joined and bedded geology, several corries have formed, and their contained glaciers have melted throughout the Pleistocene period. After the most recent glaciation period known as the Loch Lomond Stadial around 12,000 years ago, there exists a corrie containing Red Tarn on Helvellyn’s north-easterly side. These corries have eroded back to back, resulting in the formation of an arête, shaped like a knife, namely Striding Edge, and Swirrell Edge on the alternate side of this corrie. Furthermore, Red Tarn has a lip, helping to prevent water loss, as a result of rock and moraine deposits left by the glacier.

These examples clearly show the significant extent to which landforms in a valley glacier system are interrelated between different erosional landforms, from the initial snowflakes settling in a hollow to the creation of many other landforms during and after glaciation has occurred.

Ice Sheet Case Study: Minnesota

The Laurentide Ice Sheet during various glacial stages

The Laurentide Ice Sheet was a huge ice sheet, up to 2 miles in height in some places, with cycles of growth and retreat several times over the Quaternary period, from over 2mya to… today!

The geology of Minnesota is varied. There are alternating bands of igneous and sedimentary rocks. In the north, a range of mountains several kilometeres high was created by tectonic compression, made of strong metamorphic gneiss. In the Arrowhead region in the northeast, located near to Lake Superior, tectonic tilting has exposed weaker, lesser-jointed shale rocks.

Its last advance occurred between around 100kya and 20kya, where subglacial erosion carved out areas of North America, from the huge Hudson Bay to the hundreds of thousands of smaller lakes present in Minnesota and Canada, such as Mille Lacs Lake in an ellipsoidal basin. The mountains were eroded; now Eagle Mountain, the highest, is only 701m high. Part of Lake Superior and other Arrowhead region lakes were deeply eroded thanks to their weaker geologies.

As it made its final retreat, meltwater was blocked by the ice and the large “Big Stone Moraine”, forming Glacial Lake Agassiz. It was larger than every Great Lake combined, covering around 300,000 square kilometres, around the same size as the present-day Black Sea. With continued ice ablation, a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) occurred as the moraine was overtopped, around 11,000 years ago, resulting in large-scale erosion of an area 8km wide and 76m deep in Browns Valley, Minnesota. This old river is known as the Glacial River ‘Warren’, helping to carve out the modern Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, and the valley present today. With the water came deposition: large swathes of fertile silt and soil deposits have been left behind in the valley, likely from the Big Stone Moraine. It took around 2,000 years for the lake to fully drain, and it likely had a large impact on the climate, sea level and even early civilisation! [simplified]

The top left is the bed of Lake Agassiz, and the eroded area is visible too. North Minnesota.

If you’re interested, an interactive map of the glacial extent and lobes is available here, thanks to the brilliant geographers over at Royal Holloway.

Ice Lobes

There are three phases of the glaciation period you need to know, with four associated lobes. Lobes themselves form because ice wants to move under gravity, and with the Laurentide ice sheet at 2 miles high, the base of the ice sheet was under significant pressure. The thickness of the ice above, topography of the land and geology have an impact on how lobes form. In areas of lower resistance such as a valley, ice can be channelled and advance faster, forming the lobes.

Wadena Lobe

The Wadena Lobe was the first of the four main lobes that were on top of Minnesota. Arriving around 30kya, the lobe came in from the north to north-west and is characterised by the deposits it created, being from red sandstone, shale and limestone.

This deposition produced the Alexandra and Itasca moraines, forming the tilly Wadena Drumlin Field over the Wadena, Otter Tail and Todd counties, and its ground moraine reached just south of the present-day Twin Cities.

Rainy and Superior Lobes

The Rainy Lobe moved in from the north to northeast of Minnesota and deposited the St Croix moraine, made of greyish, brown greenstone around 20kya.

The Superior lobe came in from the northeast at the same time. Partially covering present-day Lake Superior, it deposited a series of basalt, red sandstone and greenstone till moraines extending southwards to the Twin Cities. Like Wadena, it too deposited drumlins.

Des Moines lobe

The Des Moines Lobe was active during the most recent glacial period (LGP), around 13kya. It moved in from the northwest, covering vast expanses of the west of the county from the most northerly point to the most southerly point. It deposited till that is tan to buff coloured and is clay-rich and calcareous due to its shale and limestone source in the northeast. In the southwest, the Prairie Coteau region has examples of terminal moraine, and outwash plains. Many of this lobe’s deposits are over 160 metres deep in the region.

Post-glacial modification

Isostatic readjustment occurs when these ice sheet glaciers retreat due to the land not being under pressure anymore. This land then typically rebounds upwards and elevations increase in the area where glaciers once lay. Fluvial activities continued to mould the landscape after full glacial retreat had occurred.

Glacio-fluvial landforms

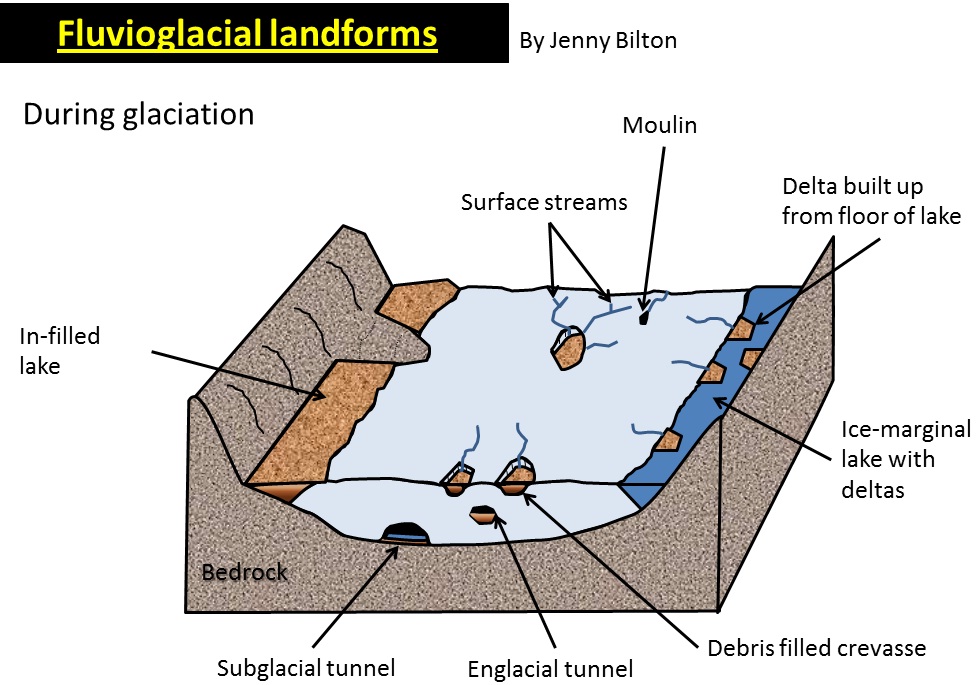

(Date studied: 23/11/2022)

Glacio-fluvial means an environment shaped by glacial meltwater.

Geomorphic means changes (morph) to the land (geo).

Glaciofluvial landforms are formed as a result of climate changes

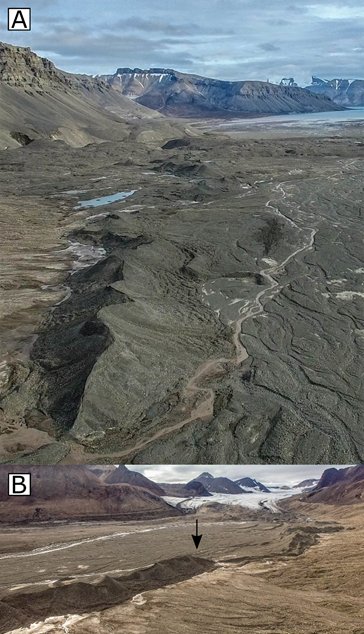

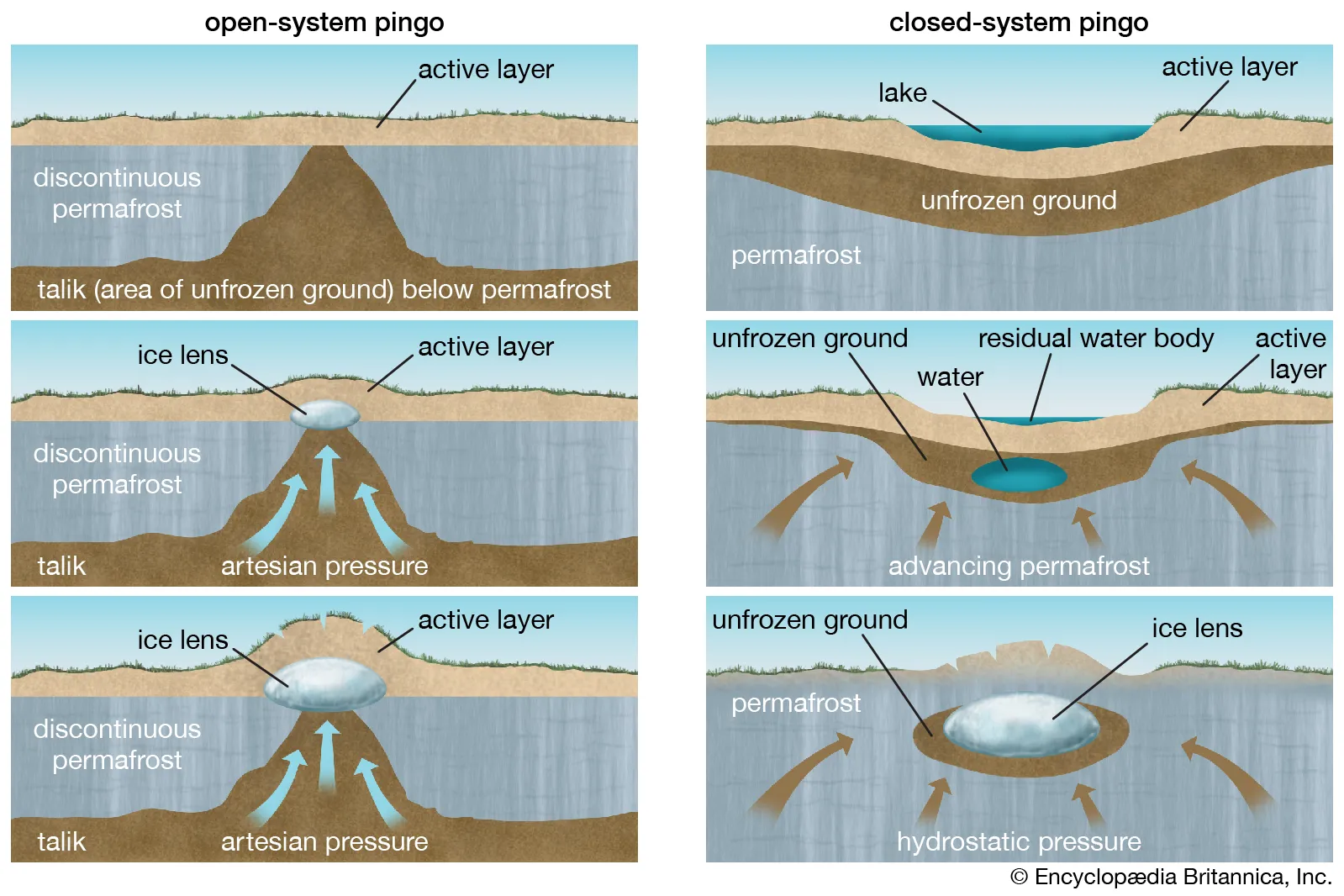

Eskers

Eskers are long, sinuous (many curves and turns) ridges made from sand, gravel and other types of glacial till deposited on valley floors by glacial meltwater flowing through subglacial and englacial tunnels.

Eskers are “elongated ridges of glaciofluvial sediment deposited by subglacial meltwater pipes”.

These tunnels and channels over time become filled up with sediment. During deglaciation, this sediment is dropped onto the bedrock leaving stratified ridges, signifying that a glacial meltwater tunnel was somewhere above it. This could be either a kame (see below) or an esker.

The general consensus is that the deposition is caused when pressure is released at the glacier’s snout, so as the glacier retreats, the point of deposition retreats too. This can describe their beaded appearance (vary in height and width throughout) with the beads of greater size representing periods of relatively slow retreat, or halted ablation. Others may say that the larger beads are caused as a result of the greater load carried by the meltwater in the summer seasons.

Here are 2 angles showing what they look like, in Svalbard.

The weight of the ice above the subglacial tunnels means that the water flowing within these subglacial tunnels is under extremely high pressure. When the ice melts, this pressure is released, so therefore dropping sediment.

Eskers are deposited unaffected by/ignorant of local topography, meaning that they can traverse over hills in the landscape.

The path taken by this pressurised meltwater is mostly controlled by the slope, size and direction of the ice surface rather than the bedrock. Because of this, eskers can be used to show the slope of the ice surface, as well as its extent! It also runs parallel to the direction of ice flow, running transverse to the glacial snout.

Topographic view of depositional landforms.

Eskers on paleo-ice-sheet beds are more abundant in areas of crystalline bedrock with thin coverings of surficial sediment than in areas of thick deformable sediment, because meltwater flowing at the bed is more likely to incise upwards into the ice to form an R-channel where the bed is hard; where the bed is deformable, meltwater is more likely to incise downwards.

You don’t need to remember that.

Examples

Many eskers are found in central Ireland, some are in Canada, as well as many in Iceland and Sweden.

Here is an example of an esker on Google Maps.

A meltwater stream is visible south of it, as well as another esker to the east.

Post-glacial climate change in Eskers

During periods of increasing global climatic temperatures, the rate of glacial ablation increases and results in more meltwater being produced. This means that there is more accumulation of sediment in proglacial areas and the length of these eskers is likely to increase or become more beaded with greater and more intense ablation periods. With faster glacial ablation, eskers will be exposed in greater number.

Kames and Kame Terraces

A kame is an irregularly shaped hill, hummock or mound made of stratified glacial till comprised of mainly sand and gravel.

There are two types of kame:

Delta kames

Delta kames can form in two main ways. Firstly, they can form due to the build-up of debris in englacial tunnels or crevasses that emerge at the glacial terminus as a result of retreat. As a result, they lose their energy, and are forced to deposit their contained load.

Another way that they can be formed is when supraglacial streams meet ice-marginal lakes. These ice margin water bodies are largely static (just sit there tbh) so the sediment they carry loses energy and gets deposited in the lake, from where this supraglacial stream enters it, often leading to a tall accumulation.

Kame terraces

Kame terraces are ridges of material near or on the valley margin. They are largely comprised of ex-lateral moraine, which was transported into the ice-marginal lake due to the supraglacial streams formed due to the warming of ice through friction with valley walls. As this is largely glacio-fluvial, unlike morainic deposits, these are somewhat sorted and stratified by the movement of water. When the glacier retreats, this sediment is dropped and collapses onto the bedrock floor.

Watch out! Many people say ‘kame’ when they mean ‘esker’! You need to know the differences between the two well. (main one is eskers are subglacial, kames are not)

This displays between kame and esker.

As climate change increases temperature levels, more meltwater is present, which transports and deposits sediment. This will result in a larger amount of all types of kame being more likely to form.

Here is an example of an esker on Google Maps: https://www.google.com/maps/cheatsheet-esker-link

A meltwater stream is visible south of it, as well as another esker to the east.

Essay example: influence of climate changes and geomorphic processes in their formation

Kames are mounds of sediment deposited by glacial meltwater or ice, found in areas where glacial ice melted and receded, leaving behind sediment deposits. The process of kame formation is complex and is a result of a variety of interrelated factors, including climate change and geomorphic processes.

Climate change is one of the most significant influences on the formation of kames. During the Pleistocene epoch, large areas of the northern hemisphere were covered in thick glaciers. As the climate warmed and the glaciers receded, large volumes of meltwater were released, carrying sediment with it. The sediment was deposited in stratified piles, forming these kames, visible in places in the UK such as the Scottish Highlands or the Lake District. This can be proven to be the result of a glacio-fluvial deposition as they are deposited in one go by melting ice, while previous meltwater surface streams moved the sediment into crevasses or glacial marginal lakes.

Geomorphic processes also play a role in the formation of kames. As the glacier erodes the landscape, valley sides’ sediment may fall onto the glacier, ranging from large boulders to sand grains. The size and shape of these kames vary depending on the type of sediment deposited, as well as the rate of erosion. In addition to erosion, other geomorphic processes can play a role in the formation of kames such as weathering. These processes such as frost-shattering and chemical weathering can break down sediment particles and form smaller particles that can be easily carried by wind or water. This can cause further accumulation of sediment in certain areas and contribute to the formation of kames. Lithification may also occur when the sediment is compacted and cemented together, forming a solid mass among the trapped sediment.

In conclusion, climate change and geomorphic processes are both important factors in the formation of kames. Climate change causes the glaciers to melt, releasing large volumes of sediment, which is then deposited in strata. Geomorphic processes, such as erosion, sedimentation, and lithification, also contribute to the formation of kames. Together, these two factors contribute significantly to the formation of kames, alongside many other factors like the topography, aspect and relief of the local region.

Proglacial lakes

Proglacial lakes form in front of glaciers, usually when meltwater streams become blocked by terminal moraines, glacial dams (trapped against a large ice sheet) or due to isostatic depression of the lithosphere into the weaker asthenosphere.

The meltwater, over time, accumulates in this area, unable to flow outwards. This is similar to how a traditional valley glacier system starts with the corrie melting and a tarn being left due to a terminal moraine blockage.

After a glaciation period, the climate typically warms up. Over time, if there is a large ice sheet blocking the water flow, this sheet will ablate, and the lake will either overflow or undermine the dam, causing a glacial lake outburst flood, or jökulhlaup.

Modern example: The Russell Fjord in Alaska is regularly blocked by the Hubbard Glacier, which can increase water levels in the fjord by up to 15m as it cannot empty out into Disenchantment Bay: Google Maps/3D Google Earth.

Outwash plains

Outwash plains are also known as sandurs. They are dominated by other landforms, including braided streams and kettles. They occur in front of melting glaciers, and are mostly flat and expansive areas. Meltwater traversing this terrain has little energy, and therefore little vertical erosional power and is more inclined to deposit material. As a result, these flat areas are created from stratified (strata; layered) sediment.

As the glacier moves over bedrock, plucking and abrasion (erosion) occurs resulting in silt and sediment being carried in this meltwater. Braided streams are dominant in outwash plains. These are very shallow streams and rivulets which carry and redeposit till due to the little energy in the system.

In summer months, there is typically higher glacial discharge and ablation, resulting in these tilly islets being destroyed by water, which has a little more energy due to increased velocity. This leads to more erosion, and these islets then go on to reform later. This makes the outwash plain have a distinct look. This can be described as dynamic.

The elevated level of erosion is typically closer to the glacial snout but then progressively loses energy.

In areas that were once glaciated, old outwash pains can be found by looking for sediment, with large angular rocks and boulders being present closer to the glacial mass and smaller, smoother rocks and sediment being further away from the glacier, similar to a typical river system aside from their origin. Outwash plains can extend for miles beyond the glacial margin (terminal moraine).

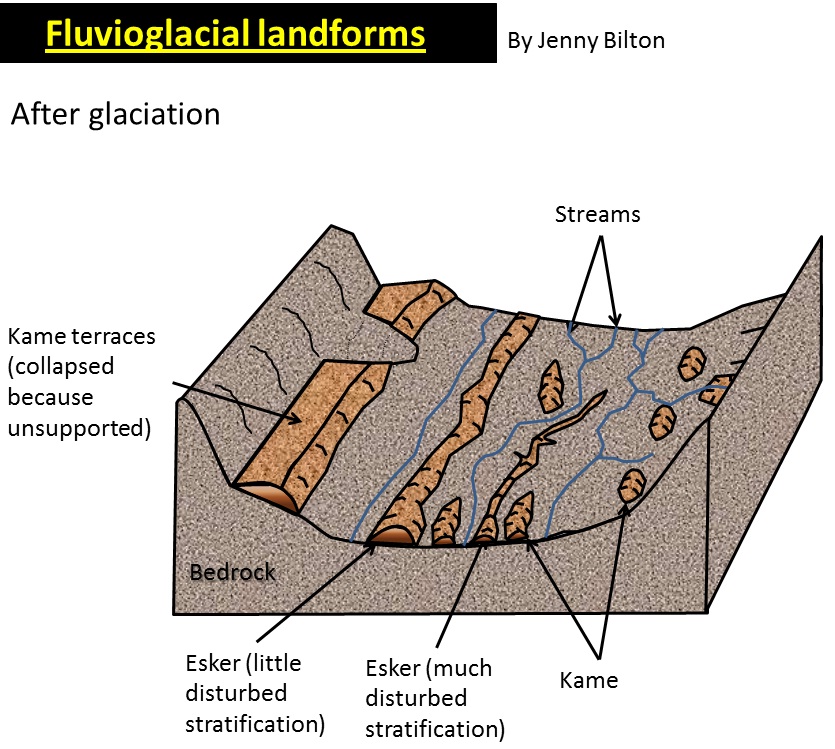

Braided streams

The general consensus is that braided rivers form instead of meandering rivers due to a higher sediment load, caused by discharge from ablation, as well as variable rates of flow.

At the end of a melting period, these lose water, lowering kinetic energy present in the system and therefore losing erosional power and increasing depositional power.

This results in material being deposited into the river channel, causing it to divide in two. Braiding itself develops when this ‘mid-channel bar’ grows downstream, as a result of more, finer material being added to the bar as discharge amounts continue to decrease. These bars, during times of exceptionally low discharge like in winter months, may become home to vegetation, becoming even more permanent. whereas unvegetated bars are less stable and often move with high discharge.

Many of these channels branch from other channels and merge to give it the ‘braided’ pattern. They are common in outwash plains due to the variable nature of ablation and meltwater amounts.

diagram of a braided stream

They are found in large quantities in south Iceland, for example.

Due to climate change, braided streams may dry up due to smaller amounts of ice present in these areas, after an initial increase in ablation due to temperature rise. This initial increased sediment load will progressively decrease as the ice mass decreases.

As a result, there can be expected to be more eroded streams, being deeper and wider, inside this outwash plain, followed then by the arebea becoming dry and tundra-like. Whilst vegetation thrives in outwash plains due to the rich minerals present in the glacial meltwater, this may also dry up in the future, becoming a barren, sandy and gravelly area with little life, or could be taken over and reclaimed by plants depending on resource availability.

Is that a braided stream AND a proglacial lake inside a valley glacier system?

Photo from Jonas Mendes.

Kettles

A kettle is a large depression in the ground formed by glacial deposition and is therefore a depositional landform. They create ‘dimples’ in the landscape around mountainous areas.

They are formed by large blocks of ice breaking from the main glacier. As the main glacier retreats, this ‘dead’ ice becomes stranded and, over time, becomes buried by sediment deposits as meltwater flows around it from the main glacier. Of course, this ice melts and its water evaporates, leaving behind a large depression, or kettle holes. Water can then fill these in again, or if not all water drains originally, resulting in kettle lakes.

Periglacial landforms

Periglacial landforms exist as a result of climate changes before and/or after glacial periods.

Periglaciation is concerned with the process and landforms attributed to the action of permafrost. Typical processes include freeze-thaw.

Being in a periglacial area means an area that is near to, or on the fringe of, glacial areas’ ice mass, such that permafrost is present. This means that there is no physical glacier system present in the area, but it is still cold, relative to surrounding environments.

Permafrost

This is also part of the Earth’s cryosphere, as well as glaciers, ice sheets, and more!

Permafrost itself is comprised of:

- the active layer (this is the top few metres or so. It is warmer as it is closer to the surface. It may become unfrozen during the summer months and vegetation may grow too.)

- the permafrost layer itself.

- talik (year-round sections of unfrozen ground, soil, and rocks that lie in permafrost areas, but itself is not frozen)

There are 3 types of permafrost:

- Continuous permafrost: there is little thawing, even in the summer. These are often in areas of high altitude and latitude.

- Discontinuous permafrost: There are some patches of consistent permafrost, but are broken up by talik extending to the active layer

- Sporadic permafrost: small amounts of permafrost largely enclosed by talik

Patterned ground

This encapsulates sorted stone polygons, stone stripes, etc.

These landforms are facilitated by the process of frost heave. Stones within the ground and active layer have a lower specific heat capacity, allowing them to cool down and heat up faster than their surrounding soil. Due to the freezing conditions, water below the stones freezes as well, and also expanding by 9%, pushing the stones upwards. Over time and many years potentially, the stones are pushed to the surface, and to a larger extent, the frost heave sorts all fine and larger material too, creating a domed surface! How exciting.

Stones which are on top of this dome then fall down to undomed areas because of gravity. This is typically every 1 to 3 metres. These rows of stones can end up connecting and forming polygonal shapes.

On slopes, between 3 and 50 degrees, these polygons become warped and are known as elongated stone polygons, or garlands. On even steeper terrain these become stone stripes.

Blockfields

Lord help me if this comes up in the exam (I am not religious)

Blockfields are believed to be formed as a result of chemical and mechanical weathering below the active layer in periglacial regions such as plateaus or mountain tops, as these are typically glacial fringe regions rather than ice-covered areas.

Over time, these processes produce an uneven, angular & bouldery landscape which is only revealed after the permafrost layer melts away, forming ‘in situ’ (alternatively by rock glaciers - which are glaciers containing a large amount of frost-shattered rocks.). Blockfields potentially formed 23 million years ago during the Neogene epoch, when the climate was relatively warmer than today; higher amounts of chemical weathering then initiated the (very slow) process of eroding formed bedrock.

Resistant rock, or tor, may be more prominent in these blockfields as they are not as susceptible to denudation (erosional processes).

On slopes above a gradient of 25o, block streams/stripes are formed as gravitational forces will move this material down a slope.

Types of mass movement

Solifluction lobes

Solifluction is the movement and “flowing” of soil and sediments

When the ground and soil on slopes is frozen during the winter, the soil particles are separated slightly and loosened by the ice which forms and expands by around 9% between these particles (frost heaving).

During the thawing of the active layer in the spring and summer months, water saturates the ground as it cannot drain easily (due to the impermeable, frozen permafrost below - it is forced to stay in the upper layer) or evaporate due to the cooler climate. Friction is reduced between these particles, which are already loose after the freezing months, as this water can lubricate them. As a result of this excessive lubrication, the soil moves downslope easily. (The extra mass from the water can also help with this.)

Soil/Frost Creep or Mass Wasting

This is a process which moves material down a slope by a few centimetres per year even on high gradients.

When the soil freezes, the particles within the slope are lifted vertically at a 90-degree angle to the slope. As the soil thaws and the particles settle, they end up slightly lower than their original position. This process is repeated over time, gradually causing the slope to shift downward.

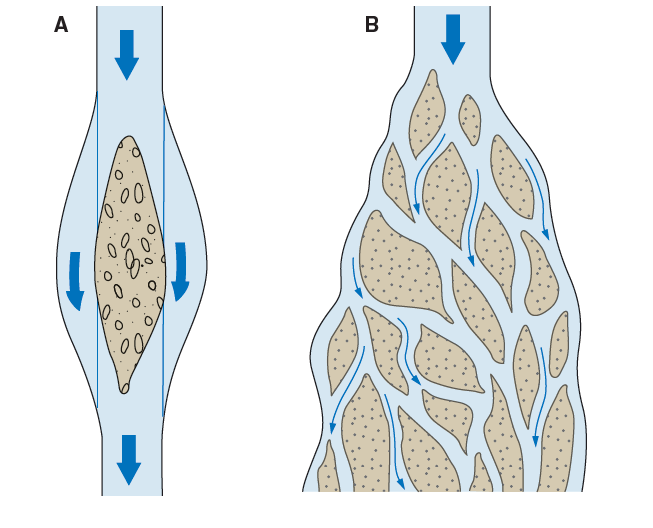

Pingos

Pingos are ice-cored hills in periglacial areas. Whilst they look the same and can be easily identified, there are two ways in which they form. They take several hundred years to form and only grow by a few cm/year. Large pingos visible in Canada and Greenland may be 600m wide and 50m tall.

During warmer climatic periods, the ice lens can melt, collapsing the dome of land above and leave a depression, typically a marshy area called an ognip, which is surrounded by “ramparts” of soil. Collapsed pingos in Wales are evidence for prior glacials and may only be 10m in diameter.

Open system, hydraulic

These are also known as East Greenland-type pingos as they commonly occur there.

Open system pingos form in areas of discontinuous permafrost, such as floors of valleys. Groundwater moves through the permeable talik and, through artesian pressure, moves upwards and cools. It feeds the ice core between the active layer and permafrost above, resulting in the ice core growing in size. Over time, the active layer above is pushed up, creating a dome of land visible on the surface.

Closed system, hydrostatic

These are also known as MacKensie-type pingos.

Closed system pingos are formed in areas of continuous permafrost. They develop in flat areas below lakes. The talik (typically fine soil, sediment or sand) below the lake is saturated by the lake, and remains as talik due to the lake’s relative warmth. Over time, the lake may become infilled with organic matter or sediment (or the water drains), reducing its insulating effect.

The permafrost thus is able to advance, surrounding the area of saturated soil, even trapping it by advancing between the saturated area and lake. Gradually the permafrost continues to advance, putting the water under hydrostatic pressure and making it rise upwards where it meets the cooler permafrost. This forms the ice core, and the hydrostatic pressure continuously feeds the ice, pushing the land above upwards into the familar pingo shape.

Ice-wedge polygons

Soil cracks when cooled quickly, just like how mud cracks when dried.

In summer, this crack in the soil fills with meltwater. Over time as many freeze-thaw cycles occur, the ice is expanded by 9% each time. This eventually results in the formation of an ice wedge. Each time the water is refrozen into ice, pressure against the surrounding soil increases, causing it to be pushed upwards, contributing to the development of these polygonal features.

Summary: Soil cracks when cooled quickly. In summer the crack fills with meltwater, and as it refreezes many freeze-thaw events take place, expanding the ice by 9% each time. This eventually results in the formation of an ice wedge.

Human activities in Glacial and Periglacial Landscape Systems

4.a. Human activity causes change within periglacial landscape systems.

4.b. Human activity causes change within glaciated landscape systems.

Case study: Oil extraction in Alaska (Periglacial)

Part of Alaska is located within the Arctic Circle, at 66.5oN.

However, since 1968, vast amounts of oil reserves have been found offshore and within Alaska itself, including inside the ANWR (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) and, more specifically, Area 1002 within it. An estimated 12 billion barrels of oil is located in this area alone, with half of it (~6bn) being available to extract using currently available techniques.

For the United States, this would provide a key resource for energy security, while at the same time reducing dependence on foreign, potentially malicious, entities, which may limit their supply, such as Russia. This weakness has been seen in Europe, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, so now more than ever the US sees this as essential.

It imported 37% of its total oil consumption in 2016 (7,259,000 barrels per day).

Hydrological processes

Gravel extraction adds insult to injury. The loss of gravel from fluvial systems can change the composition of the river profile and exacerbate damages further downstream from the extraction site. Extracting gravel from a glacial outwash site has been proven to lower the groundwater levels by over a metre in a 2km radius as well.

Urban heat island effect

Barrow, Alaska is the northernmost settlement in the USA and the largest native community in the Arctic, with a population of 4600 in 2000, increasing from just 300 in 1900. Recent decades have seen an increase in mean annual and winter air temperature, with an earlier snowmelt in the village and a weaker snowmelt trend in the surrounding tundra.

The urban heat island (UHI) effect is a phenomenon where urban areas are significantly warmer than their rural surroundings due to activities by humans, like air conditioning, hot water pipes and road building.

A strong urban heat island (UHI) was found during winter, with the urban area averaging 2.2 °C warmer than the hinterland. There was a strong positive correlation between monthly UHI magnitude and natural gas production/use, ultimately resulting in a 9% reduction in accumulated freezing degree days in the urban area.

This excess heat is mostly generated from:

- The burning of fossil fuels during flaring. This increases the carbon dioxide concentration in the local atmosphere, resulting in an enhanced greenhouse effect. This increases the amount of terrestrial radiation within these areas.

- The absorption of solar radiation by urban surfaces - solar insulation warms up these more than surroundings as tarmac/gravel structures are black, which absorb more radiation.

- The reduced evaporative cooling from vegetation.

As a result of this input imbalance, permafrost can thaw, leading to changes in the landscape and the release of trapped carbon dioxide and methane, which can further contribute to climatic changes in these areas locally, as well as internationally, as permafrost contains 1.5 trillion metric tons of carbon (that’s 1,500 petagrams if you’re fancy like that - or double than what’s in the atmosphere today).

This thawing can furthermore lead to infrastructure damage, as roads and buildings can be damaged by the shifting of the ground due to solifluction.

Thermokarst

A landscape characterised by depressions due to the thawing of the ground ice which comprises the active layer and permafrost below. Visible in the Alaskan North Slope.

Case study: Kárahnúkar HEP Dam, Iceland

This dam (or, collection of three dams) was built in East Iceland on a large proglacial lake, sourced from one of the largest glaciers in Europe. It is actively retreating, so provides water to the dam which can then be used as hydroelectricity. The dam itself was finished in 2007 and is large enough to be seen from space.

The dam could provide enough energy for all Icelandic homes and small businesses, but instead, all energy provides the nearby aluminium smelter called Alcoa.

However, there has been widespread backlash over the project, as it flooded over 400,000 acres of unspoilt highland wilderness which was the second largest unspoiled area in Europe. In total, almost 750,000 acres of land was affected by the construction of the dam, which is around 3% of Iceland’s total land mass.

The dam was built as Alcoa produces 2% of the world’s aluminium supply, and global financial markets at the time of construction were expected to make a significant number of jobs, and this aluminium industry was expected to make up 10% of Iceland’s total GDP. This has not happened yet, and the price of aluminium had almost halved just two years after construction finished, and has not recovered to this level seldom for market bubbles seen with the Russian invasion, which stressed productions of almost all raw materials.

Glacial meltwater, or glacial milk, is released by the Vatnajökull glacier and flows into the lake blocked by the dam. This glacial meltwater is known to have a high concentration of sediment within it, and as such reduces the capacity of the dam over time. This is because the suspended sediment at the base of the water solidifies when deposited, as there is little kinetic energy at the bottom to keep suspended sediment floating. Over time, the base level of the lake increases, reducing overall water capacity, until this excess sediment is ‘purged’ by the dam management system, which may happen annually.

Here’s a video of sediment getting purged

That’s the end for glaciation! I hope you found it useful.

What if I told you about Paraglaciation and Paraperiglaciation as well?

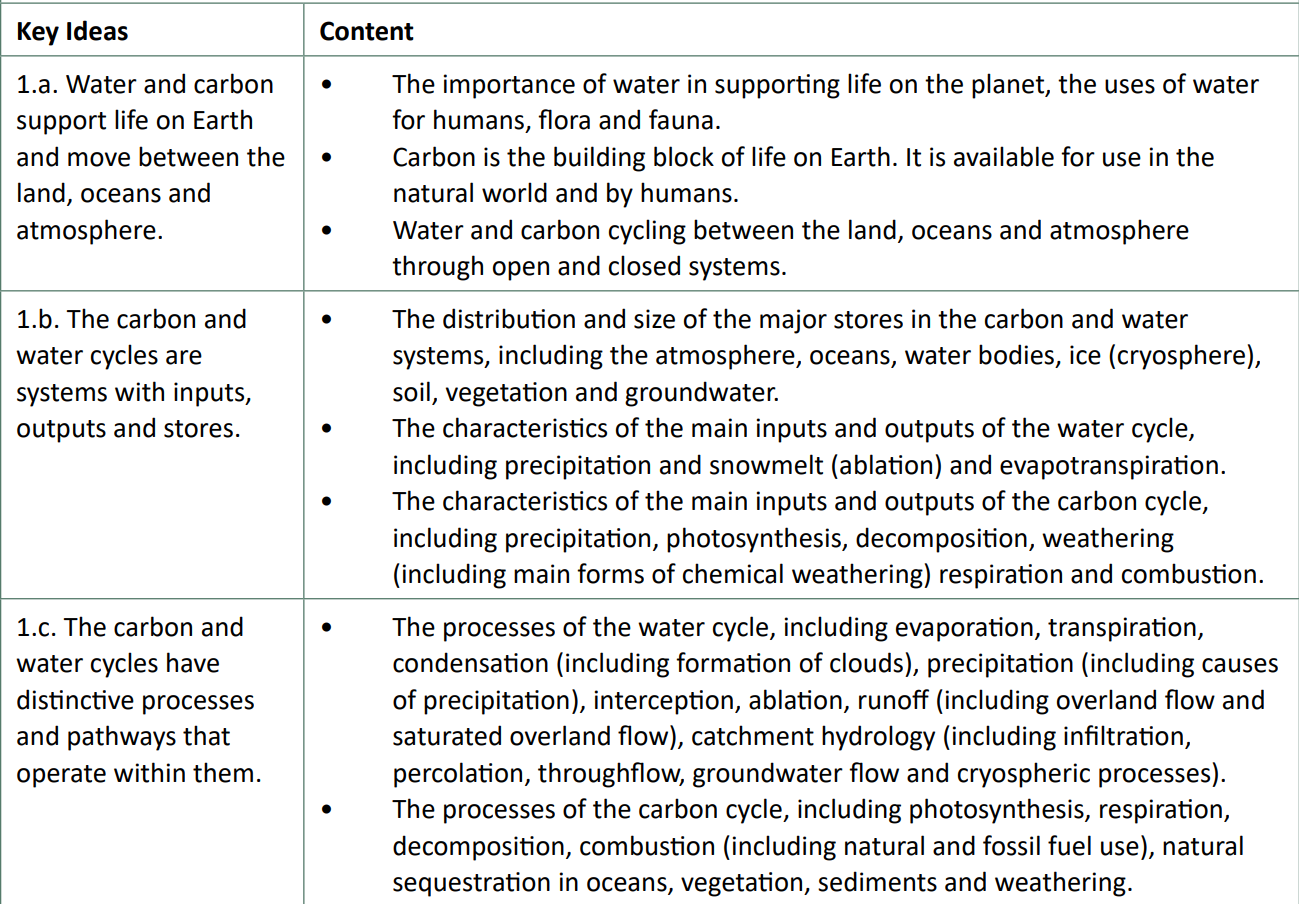

1.2 - Earth’s Life Support Systems

Section wordcount: 8796

giving earth life support - created with dall-e 3

“Without water and carbon I literally would not be here” - a wise man, 2024

1. How important are water and carbon to life on Earth?

The short answer to this is that the water and carbon cycles are very important.

The long answer? Well…:

Introduction to water

1a. Water and carbon support life on Earth and move between the land, oceans and atmosphere.

Water is a fundamental prerequisite for life, not just on Earth but it is considered by scientists as an essential necessity for any sort of life in the universe.

The Circumstellar Habitable Zone, or Goldilocks zone, is the habitable area around a star that is neither too close nor too far so that conditions for life are too hot or too cold, and categorised by allowing liquid water to be present. Otherwise, the water would be evaporated or be as solid ice. As such, liquid water allows life to form. Depending on the star, this zone can be further or closer to it, or the zone itself being wider or smaller.

It is described by astronomers as:

“The area around a stellar object which contains liquid water, making it habitable. The regulation of temperature and radiation facilitate respiration and photosynthesis”.

Water is essential to supporting life. The atmosphere is sustained by a continual cycle of evaporation and condensation through cloud formation. Water vapour itself is a very potent greenhouse gas, which regulates and moderates global temperatures: the climate is 15 degrees C warmer with water than without. As sun rays collide with the molecules in water vapour, they heat them up, causing them to vibrate and let off heat. In addition, water vapour is excellent as stopping short-wave radiation from causing harm for the biosphere. The greenhouse effect by water vapour prevents some long-wave radiation reflected from the Earth from exiting. It makes up 65-95% of all the biospheric mass, including in people, flora and fauna.

Water itself is in a closed system, meaning that water cannot enter or leave the Earth. As the water cannot exit or enter, it is transferred, stored and moved around inside the system. This is known as the global hydrological cycle.An open system within the overall closed water cycle system may be a drainage basin: water can enter and exit at any time.

| Store | Size | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Ocean | 1.33b km3 | 96.5% |

| Cryosphere | 24m km3 | 1.76% |

| Aquifers | 23m km3 | 1.69% |

| Lakes | 176k km3 | 0.013% |

| Pedosphere | 17k km3 | 0.0012% |

| Atmosphere | 13k km3 | 0.00093% |

| Rivers | 2.1k km3 | 0.00015% |

| Biosphere | 1.1k km3 | 0.000081% |

- Data updated to match latest scientific research.

Introduction to carbon

Carbon is the building block of life on Earth. It is available for use in the natural world and by humans.

It is found across the planet, in a wide variety of stores, and is measured in Petagrams of Carbon - PgC - which is the same 1 gigaton. It is stored as a gas in the atmosphere, in oceanic sediments, and is used in living organisms to… continue living, amongst other things. Carbon is also very useful as we can use it to power various electricity generators through hydrocarbons like oil.

Similarly to water, carbon is a closed system on Earth, but on a more local scale such as a rainforest it becomes an open system.

| Store | Amount | Format |

|---|---|---|

| Lithosphere | 100,000+ PgC | Fossil fuels, sedimentary rocks |

| Hydrosphere (deep) | 40,000 PgC | Mostly CaCO3 from dead shelled organisms and bicarbonate ions. |

| Pedosphere | 2,000 PgC | Litter from dead or decaying matter and near-surface soils |

| Cryosphere | 1,700 PgC | Permafrost |

| Hydrosphere (upper) | 1,000 PgC | Dissolved CO2 from atmospheric dissolution |

| Biosphere | 650 PgC | Living organisms, flora and fauna. |

| Atmosphere | 800 PgC | Carbon dioxide |

The data is somewhat variable and differs between scientific research.

Inputs, outputs and processes of water

1b. The carbon and water cycles are systems with inputs, outputs and stores.

1c. The carbon and water cycles have distinctive processes and pathways that operate within them.

In the global hydrological cycle, there are many interrelated processes, stores, inputs and outputs, similar to that of a glaciated system. Flux is a term used to measure the rate of flow between stores, through mass over unit time (e.g. 3m/s). In total, around 505,000km2 of water is moved annually around this system.

Evapotranspiration

Evapotranspiration is the term used to denote the transfer of water into the atmosphere, combining evaporation and transpiration. Energy, such as insolation, when added to a mass of water like an ocean, increases particles’ energy and breaks the bonds between them, allowing for a state change to gas as water vapour, which then rises. This is evaporation. Transpiration on the other hand occurs only from the biosphere and mainly plants - this accompanies the process of respiration and photosynthesis. Leaves and plant surfaces lose water through their stomata via evaporation, and this water is replenished through effectively pulling more water and nutrients from the roots through the plant. On a local scale this may be insignificant but on a wider, perhaps national scale such as the Amazon Rainforest, the amount of water transpired through the plant, and evaporated by rivers and other stores, contribute significantly to changing global weather patterns. In total, transpiration accounts for around 10% of atmospheric water vapour.

Water in the soil (pedosphere) is the most likely to be absorbed by trees and vegetation, which transpire and release water into the atmosphere. You can use this as an example of a rapid flux, from the pedosphere, to the biosphere and then into the atmosphere, perhaps in under a day. An oak tree can transpire over 150,000 litres of water per year. In total 10% of water vapour present is transpired by plants (biosphere)!1

Precipitation

One of the main processes in the water cycle is precipitation. Simply put, this is when water leaves the atmosphere through any form, such as rain, snow, sleet or hail. When water vapour reaches the critical dew point (temperature at which air becomes saturated with moisture), it condenses in the atmosphere as clouds. Provided that there exists condensation nuclei, then clouds will form. As these nuclei of ice crystals or water droplets aggregate, they become too heavy to be suspended in the atmosphere, thus reaching a critical size and then fall to the surface as precipitation. This process is known as the collision-coalescence theory.

Water produced by precipitation is then collected in a drainage basin and moves into rivers through runoff - a combination of processes including overland flow, in addition to soil infiltration, ground percolation and subsequent throughflow and groundwater flow. Most of this water will then enter the ocean again, ready for the cycle to repeat, or percolate further into permeable rocks and be part of an underground aquifer.

Some key points:

- Where precipitation occurs at high altitudes or in cold environments, snow is likely to form, and potentially remain on the ground for a long time, increasing the lag time visible on flood hydrographs.

- Duration is the length of time a period of precipitation lasts. Climatic depressions or frontal weather systems may cause this; there may also be high rates of overland flow with flooding for long durations.

- Intensity is how much precipitation falls over a given time period. This can also have an impact on reducing lag times with high intensity, causing more overland flow due to less time to infiltrate into the soil. The amount the soil can absorb is the infiltration capacity.

- Precipitation may also vary seasonally, with greater intensity in certain months. This variation can increase or decrease the amount of water in rivers and lakes.

Precipitation may make it to the ground in a catchment area and be subject to the processes involved in catchment hydrology. Or, it may be intercepted by trees and vegetation,

Ablation

Ablation, which you might know from the Glaciated Landscapes unit, is the result of snowmelt. Glaciated environments and ice sheets contain the second highest amount of stored water on the planet - behind that of oceans - at 29 million cubic kilometres. Although most is in polar glaciers which take a longer time to melt due to the much colder temperatures, water is still released through meltwater, calving and sublimation. And from retreating alpine glaciers.

In addition, permafrost melting can also contribute to the creation of extra ponds and lakes, visible in thermokarst landscapes in the Arctic Tundra. This change occurs seasonally.

This video is a great example of the risks to humans when there is too much ablation. [VIDEO]

Condensation & cloud formation

There are some fundamental principles of cloud formation you need to know:

- HOT AIR CAN HOLD MORE MOISTURE THAN COLD AIR. (Greater energy allows for more gases)

- As air rises, it always cools, at a rate of 0.65 degrees C per 100m or so.

- Due to gravity, there are fewer molecules of air above the original air pocket. Therefore the pressure is lower, and the air pocket expands. With this expansion there is greater room for the molecules to collide, reducing kinetic energy. A reduction in energy lowers temperatures.

- Air rises when it moves over a mountainous region, or wind from below moves over a mountain.

- The atmosphere has less pressure with altitude. Therefore, the same amount of air in a ‘parcel’ will occupy a greater area at higher altitudes.

- The dew point is the critical temperature at which air can contain purely water vapour at a given pressure. Beyond this point, cooling results in condensation as no more moisture can be held as vapour.

Air moves in ‘parcels’ which have their own temperatures, humidity, etc.

Adiabatic expansion

When air cools or expands adiabatically, this means that there is no heat exchange with the environment. The parcel of air purely changes based on the pressure being exerted on it by the atmosphere.

- The environmental lapse rate (ELR) is the decrease in air temperature with altitude for a specific time and place. this is 6.5 degrees C per km on average

- The dry adiabatic lapse rate (DALR) is the rate at which unsaturated air cools during ascent, or warms during descent. The DALR is 10 degrees C per km.

- The saturated adiabatic lapse rate (SALR) is the rate at which air at its dew point (and therefore condensing) cools as it rises. Condensation releases latent heat, making this lower than the DALR at around 7 degrees C per km.

These are significant as the determine how “stable” the atmosphere is.

When the sun warms an area of land, it creates heat, which warms up the air around it. As this air is unsaturated, it will decrease in temperature at the DALR. As it continues to increase in altitude, the temperature reaches the dew point, and the air becomes saturated.1

Cloud formation

Clouds main form through convection. As an area of ground warms, the local air “parcel” rises - this is atmospheric instability. For this example, let’s say that the dew point is 10degrees C lower than the temperature at the surface (as a result of insolation). Therefore, as the air has not reached its dew point, it moves upwards at the DALR, and reach the dew point at an altitude of 1km. Once it reaches this level, condensation will occur, forming a cloud. However, there is still convection occurring, as the air parcel is still warmer than the surrounding ELR. Eventually, the ELR and SALR will be in equilibrium at a given altitude, which marks the point of atmospheric stability and halt of cloud formation

Different areas at different times have different dew points. and rates of ELR