Disease Dilemmas Complete Notes

Note that this is an incomplete cheat sheet. No ads will be shown. Eventually, the content here will be merged into the main cheat sheet. Happy revision!

Last update: 15/01/2024 22:38

Word count: 4,807 (25,446 characters)

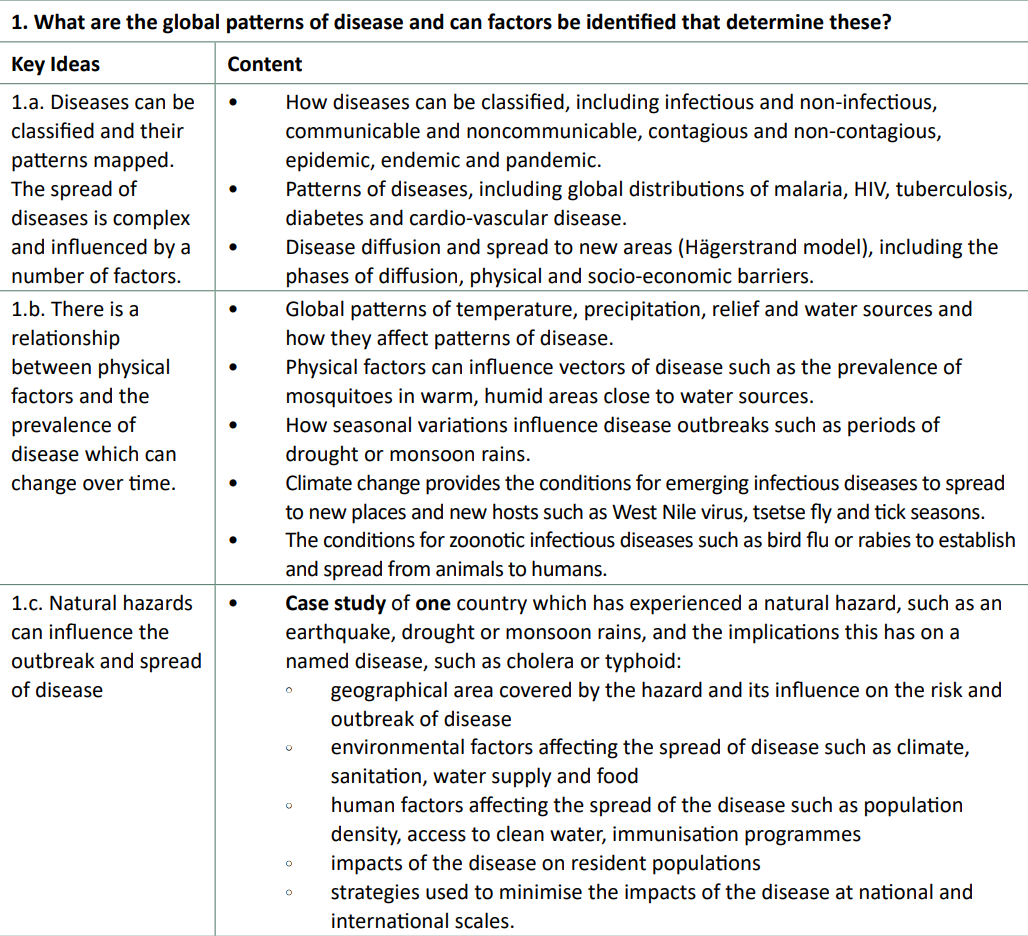

1. Global patterns of disease

All types of diseases can be categorised into distinct categories depending on how they spread, how frequently they spread, who they spread from and to, and how many people spread them.

Communicable diseases are diseases which spread from host to host through means such as direct contact, contact with contaminated material, through vectors or airborne particles. Broadly, these ones can spread.

Non-communicable diseases cannot be spread between people. These are a result of lifestyle choices and genetic factors

Infectious diseases are those which are spread by pathogens from any host to any host, with any form of contact.

Non-infectious diseases cannot be caused by pathogens between hosts.

Contagious diseases are those which spread between people through direct or indirect contact.

Non-contagious diseases cannot be transmitted from one person to another. However, they may include those transmitted through vectors.

For example:

- Malaria is communicable (can spread), infectious (spread by a parasite) but non-contagious (cannot go directly from person to person)

- Skin cancer is non-communicable (can’t spread), non-infectious (not spread), and non-contagious (can’t be caught from someone else)

In addition, diseases can diffuse in different ways

- expansion diffusion: increasing in geographical area, typically decreasing in severity

- relocation diffusion: move from one area to another

- contagious diffusion: spread from person to person

- hierarchical diffusion: spread along transport links

All of these are linked to Hargerstrand’s diffusion model.

Be careful when applying this to outbreaks like Covid where the model assumes that people will always want to travel and constant movement. Lockdowns can result in this model’s predictions being broken.

Different scales:

- endemic: persistent in a restricted geographical area

- epidemic: an outbreak that has spread to a larger population

- pandemic: an outbreak that has spread worldwide

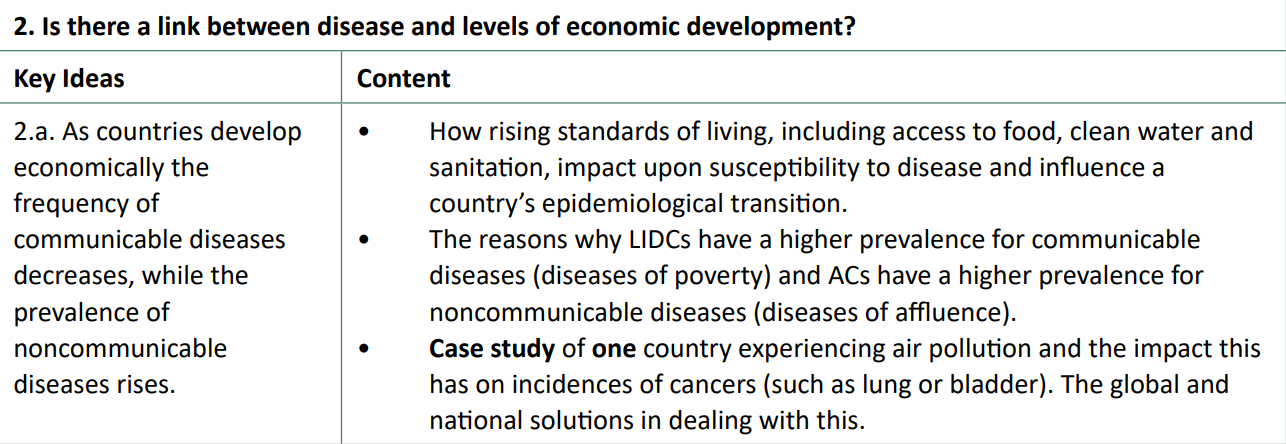

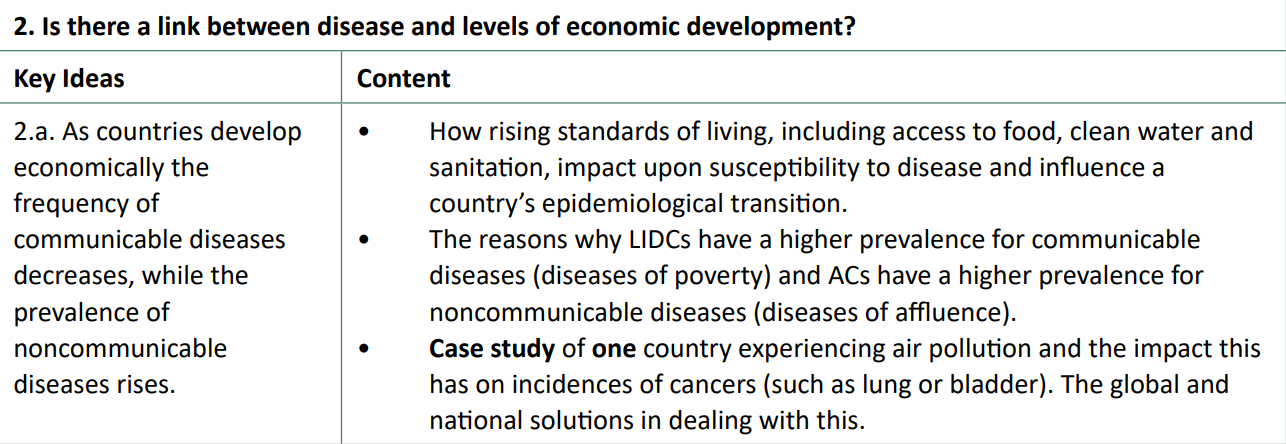

2. Is there a link between disease and levels of economic development?

### Patterns of diseases

### Patterns of diseases

Malaria

Malaria is an infectious, non-contagious disease. It is concentrated around the tropics, mostly in Africa, Central America and South/Southeast Asia - in other words, it is endemic to specific countries and epidemics can occur, but not pandemics. The Anopheles mosquito, which is the fector which transports the Plasmodium parasite, is most abundant in warm and humid environments, but not large urban areas.

Facts:

- In 2018, 220 million people were infected with the disease.

- In total, there are 3.2 billion people at risk in 97 countries.

- It is estimated that half the world’s population since the beginning has died from this disease.

HIV/AIDS

This is an infectious, contagious disease.

Case study: River flooding, Bangladesh

Bangladesh, bordered by India and Myanmar (synoptic link to Global Migration) is a deltaic country, situated on the world’s largest river delta - the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta.

Flooding from this river is a significant part of the livelihoods of Bangladesh’s population. 60% live in rural areas, mostly in the primary (agricultural) sector; 80% of the land area benefits from the flooding extent. There are several hundred permanent waterways which move around a billion tonnes of fertile soil, fuelled by glacial ablation in the Himalayas (synoptic link to Glaciated Systems) where peak melting coincides with the monsoon season. On top of being low lying (the average elevation is just 9 metres; 10% is below sea level 2, which leads to over a third of the country’s land area regularly flooding in the monsoon season. 1

This isn’t all positive, however. In the short to medium term, climate change is exacerbating risks by increasing the volatility of glacial systems, increasing the magnitude of discharge and therefore magnitude of the flooding in these low-lying areas.

percentage-of-area-inundated-in-Bangladesh

In 2020, the monsoon rains were of unprecedented scale. In the first half of the monsoon season, 40% of the land was inundated. This led to an epidemic of various water-borne diseases, including hepatitis, diarrhoea, typhoid and cholera. Although only 83 people died, 1.3 million homes were damaged (and 3/4 of a million flooded), affecting 5.4 million people (1 in 35 people) 4. The amount of crops destroyed was over 150,000 hectares, 3 which has knock-on effects for future years: consecutive years with bad flooding can decrease communities’ resilience due to less stored money from agriculture, especially true as half of the Bangladeshi population live below the absolute poverty threshold and this can increase the susceptibility to disease outbreaks with a lack of nutrition and strength to be able to fight diseases like diarrhoea which is especially deadly for children under 5 years old. As an LIDC, this is especially true: the population pyramid is swayed in favour of younger ages (5% are under 5, compared to the average in ACs which is 6x fewer). This was seen in Bangladesh with these floods: the contamination of water supplies such as wells resulted in 4,500 people becoming ill with diarrhoea alone. On top of this, just under 2,000 schools and educational facilities were destroyed in the floods too.

Bangladesh, although has its problems, is improving too. The threat of more severe flooding in future years and stronger cyclones has prompted both the government and NGOs to intervene. Female education and nutrition has significantly improved, with an emphasis on breastfeeding which reduces the likelihood of deadly waterborne diseases like diarrhoea being introduced into vulnerable babies’ and children’s immune systems. The Government allocated 14,410 tons of rice to be given to those affected. Oral rehydration solution was given to treat those moderately dehydrated, with water purification tablets being used to treat water supplies in large population centres, significantly reducing the risk of waterborne illness contamination and subsequent infection.

Extra reading available: here

2. Is there a link between disease and levels of economic development?

Case study: Air pollution and cancer in India

India (Bharat), now the most populous country, is classified as an EDC with an HDI of 0.633 and a GNI per capita of $7130 PPP. However, levels of air pollution in this expansive nation are… pretty bad. 21 of the 30 most polluted cities globally are in India. 99% of Indians breathe air above the WHO’s “safe” levels of PM 2.5 concentrations of less than ten micrograms/m3. With a population of 1.4 billion, half of them are expected to live for three fewer years because of this - and some urban residents in the capital (New) Delhi and other cities like Hyderabad and Gurugram are expected to live for 5 or even 10 or more years shorter!

Over the past 2 decades, fine particle concentration has increased by 69% across India, reducing the life expectancy by around 2.4 years nationally.

Air pollution here is largely caused by particulate matter (PM), like NO2, S02 and O3, emitted from vehicles, factories and coal-based factories. Biomass in rural areas also contributes to this: burning paraffin and animal excrement increases indoor air pollution so much that up to 1 million people die prematurely annually because of this. This is visible as photochemical smog - which can cause acid rain.

PM 2.5 are particulates smaller than 2.5 micrometres in size, which can penetrate and remain persistently in the lungs and interfere with DNA, causing mutations like cancer and increasing the probability of other non-communicable and chronic illnesses. Bronchitis, asthma, lung cancer, and CVDs (heart disease)

In many cities such as Bangalore, around 50% of children suffer from asthma. This is the highest worldwide.

In Delhi, PM 2.5s are at 24x the safe level - and increasing. A reduction to safe levels would benefit life expectancy more than eliminating unsafe water access and eliminating poverty, combined.

Air pollution is having a significant negative impact on India’s economic output and various social factors. There is an added burden on healthcare systems to accommodate for lung cancers and other cardiovascular, chronic illnesses when the country has not fully made it out of the Age of Receding Pandemics (Stage 2) of the epidemiological transition model. The particulate matter at such high levels has an impact on the brain, reducing its function by several percent and potentially reducing educational attainment and the chances of students contributing to the economy through high-skilled employment. Even if they do, the reduced life expectancy will shorten the times they will be able to work, earn, spend and reinvest in the economy.

Nearly 1.67 million deaths and an estimated loss of USD 28.8 billion worth of output were India’s prices for worsening air pollution in 2019. 1

Respiratory diseases are 1.7x higher in Delhi, with a 40% decrease in lung function because of air pollution. In addition, there are 20% more non-smoking-related lung cancer diagnoses each year, with a total of 1 in 68 males being diagnosed with lung cancer in one year alone.

Solutions

However, there is a silver lining to the smog cloud. Gujarat, a state in the west of the country, has set a legal limit on pollutant emissions for industrial plants. The government gives out a set amount of emission permits to companies, and should certain factories require more emissions, they must trade these permits to raise their emissions allowances. This financially incentivises businesses to invest in less emissive processing facilities, reducing air pollution, whilst providing a revenue stream for the local authority to tackle the effects of heightened levels of emissions, in addition to tackling a root cause of this through the trading permits.

Petrol and diesel subsidies have been scrapped in some areas (these fuels power large amounts - 1/3 - of electrical production) and further, 14 Indian cities are expanding the use of high-speed metro systems - encouraging clean, fast public transport which reduces traffic congestion.

In rural areas, zigzag brick kilns which reduce coal consumption by 80% have been fitted in various communities, despite slow progress. Burning stubble in fields - a huge smoke pollutant which wind frequently carries from rural to urban settlements, making up 17% of India’s emissions - is also in the process of having additional restrictions.

Despite all of these advances, the introduction of legislation like this has been slow and there are greater priorities for the moment such as increasing living standards across the country - 15% are still living in multidimensional poverty. There is currently no legislation controlling levels of nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide with vehicle emissions. Economic incentives to further grow the country’s economy may be hampered if legislation like this is forcefully enacted, therefore, the government is betting that allowing significant economic development now will allow them to put laws in place in the future as the country develops, without being of detriment to all citizens.

Further reading: Wikipedia

Global solutions to air problems

In 1997, there was the legally binding Kyoto Protocol. It created agreements on reducing carbon emissions around the world, such as by 2012 there will be 22% lower emissions. In comparison to 1990 in the EU, however, global carbon emissions increased by 65%! Despite this, the goal was achieved and even by 5% in the EU. This caused industries - directly or indirectly - to move and relocate away from the EU. Carbon trading systems were also considered too complex, would not help to reduce emissions, and only included those countries that had already been industrialised.

In 2015, this protocol was replaced by the Paris Climate Convention. It agreed to reduce CO2 emissions below 60% of 2010 levels by 2050 and to keep global temperature rises below 2° C in comparison to the 1900 average. Ideally, this was set to 1.5°, but this is considered too difficult.

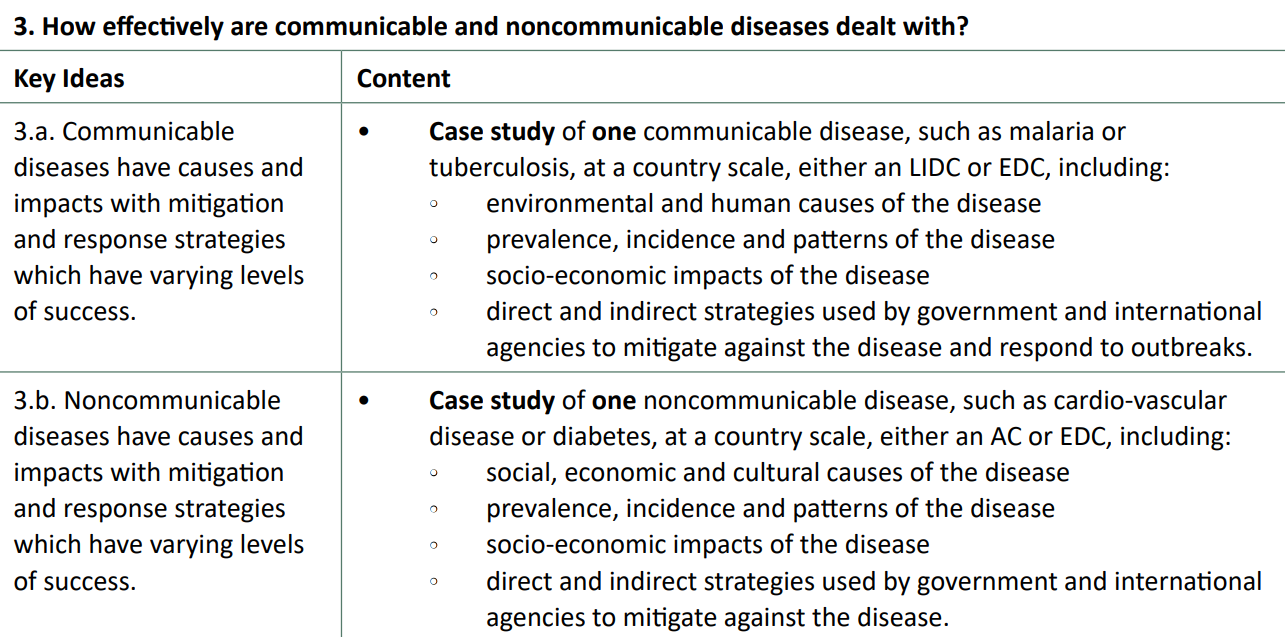

3. How effectively are communicable and noncommunicable diseases dealt with?

Case study: Malaria in Ethiopia (LIDC)

Malaria, one of the world’s most deadly diseases, is estimated to have killed around 5% of all humans who have ever lived [1]. It is a communicable, infectious but non-contagious disease. More specifically, female Anopheles mosquitoes inoculate the Plasmodium (primary P. vivax) parasite into humans - where it infects liver cells and then moves to red blood cells - with no other known hosts.

Sporozoites inoculated by the female Anopheles vector enter liver cells, rupturing and releasing mature merozoites which move into red blood cells.

200 million cases of malaria were reported in sub-Saharan Africa to the WHO. In Ethiopia, 3/4 of the land area is considered endemic, putting 2/3 of the population (60 million) at risk of contracting the disease, where around 5 million cases are reported, alongside 70,000 deaths, per year. Malaria can also be caught again, as it can take many reinfections to build up sufficient immunity to become protected against it. [2]

The epidemiology of malaria is unevenly distributed. Areas such as the Gambella province, situated to the west of the Ethiopian highland mountains (relief rainfall) are in a lowland area and malaria is endemic. This area, where humid and warm, >30 degrees conditions mix with stagnant water pools provides ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes (which require >20 degrees C). In the highlands, altitudes reach over 4,000m and are malaria-free thanks to their cooler temperatures. Addis Ababa, the capital, is in a malaria-free area; it is also the 5th highest-elevation capital city in the world.

In addition, large-scale population migration occurs at the same time as the rainy season, which is also the season of peak malarial transmission. Many agricultural workers migrate temporarily from the malaria-free highlands to the lowlands. Farmers often sleep in airy barns and work into the night, when transmission is at its highest. Irrigation, in the Awash Valley and Gambella, has exacerbated the risk of mosquitoes due to more stagnant water pools required to harvest the most common foods like rice.

Socio-economic impacts on Ethiopia

As with all communicable diseases, it is the poor who are the most susceptible and carry the burden of the disease. Malaria accounts for 40% of the national healthcare expenditure and 10% of hospital visits. The cyclical nature of the disease results in particularly bad epidemics every 5-8 years which have been seen to overwhelm health services. On top of this, tourism is stifled by the malaria warnings, despite being a beautiful country along the East African Rift.

The uneven epidemiology also affects food security, the environment and social factors. Addis Ababa is able to accommodate high population densities due to the relatively developed infrastructure and malaria-free state. As people understand the risks of malaria, many refuse to work in the lowlands and overexploit the already poorer-quality farmland compared to the nutrient-rich lowlands. It is therefore not surprising to learn that, when harvests are particularly bad with droughts (short-medium term becoming worse due to climate change), the country is susceptible to damaging famines. Economic measures such as DALYs (Disability-adjusted life years) ) lost also show that malaria has a significant impact on the population: 30% of all life years lost are because of this, reducing economic output potential further.

Mitigation strategies and responses

There has been little medicinal development concerning anti-malarial treatments for over 50 years. Chloroquine, which raises the blood pH and therefore that of the parasite, killing it, is becoming increasingly resisted by the parasites and can be toxic for those who take it (socioeconomic impact too). As a result, the government and NGOs have been working together to mitigate the risk of this disease.

The U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) has ‘invested’ half a billion dollars into antimalarial programs, such as providing around 50 million insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) to residents, prioritising pregnant women and those under 5. Indoor residual spraying (IRS) has also been used extensively, in over 12 million homes and public places. Child death rates have fallen by over 35%, and 70% of homes now have protection from an ITN or through IRS. In total, the number of malaria-induced deaths has declined by 50% in just 15 years from the peak in 2004. These are some examples of indirect mitigation strategies.

The WHO’s Global Technical Strategy has also targeted Ethiopia as part of a push to eliminate Ethiopia worldwide by 2030, a strategy that worked for Smallpox during the 20th Century. It remains to be seen how growing resistance and increased incidence may have an effect on the longer-term outlook.

Case study: Cancer in the UK

Cancers are non-communicable, non-infectious and non-contagious diseases. One in two people in the UK are expected to suffer from cancer in their lifetimes. One in four people to die in England in 2021 was due to cancer.

Carcinogen: something likely to cause changes to a cell’s DNA. Too many DNA alterations may cause

Rates of cancer in the UK are not evenly distributed. The northeast has the highest rate of colon, lung and rectal cancer, as opposed to areas like London with the lowest rates of cancer in the country, where prostate cancer is highest.

Melanoma, a type of skin cancer, has the fewest cases in more deprived communities according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation compared to lesser deprived communities.

Lung cancer has significantly more (170%) cases in the 50% more deprived communities compared to the least deprived half.

There is a clear link between smoking and at least 15 different types of cancer. 7 in 10 lung cancer cases are caused by smoking; it is also the most common cause of cancer death in the UK

Socio-economic impacts on the UK

A thousand people get diagnosed with cancer in the UK every day. Thousands more get informed that someone they know has been diagnosed. 500 people die daily from cancers. Incidence, in areas independent of deprivation status, will increase by over 40% by 2035 for half a million new cases annually.

The workforce is affected: 120,000 people below the age of 65 are diagnosed every year with cancer. They are likely to leave the labour force for many months at a time during treatment, and many may never return to work - some are too physically in pain or fatigued due to the secondary effects of chemotherapy, for example, to return. The UK has one of the highest rates of carers for those with cancer in the “western” world with over 1 million people caring for someone with a terminal condition, out of work or undergoing treatment. In addition to the 50,000+ working-age people who die of cancer each year, the economic losses of this quickly add up to tens of billions of pounds annually, with hundreds of thousands never able to work again.

Mitigation strategies and responses

Environmental factors can explain a large percentage (~ two-thirds) of cancer cases in ACs like the UK. Skin cancer melanoma is increasingly becoming a large risk as people ignore the risks of sunbathing, purchasing sunbeds and buying more accessible cheap holidays abroad - only 11% of people say they always use suncream in the UK ([2]). Social media, coupled with increasing wealth and accessibility of products, has idolised the view of a tanned look, whereas in reality unprotected exposure to significant UV rays invisibly damages and ruptures parts of the skin and can interfere with DNA, causing melanoma skin cancer, and reached the highest level in 2023; increasing almost a third in just a decade [1] for an average of 3% per year. To combat this, the Met Office now issue weather warnings and forecasts for UV levels, including for the most popular holiday destinations. The Sunbeds (Regulations) Act 2010 forbids the supply of tanning devices to those under 18. Finally, additional education in schools and publicity campaigns have also been increasingly employed by the government to warn the public about melanoma.

In addition, (international) charities and organisations have employed a range of measures to tackle cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support and Cancer Research UK are some charities that both employ direct and indirect strategies. Firstly, Cancer Research UK invest large sums of their donations into various cancer drugs, and treatments such as immunotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The research done in these fields has resulted in many clinical trials which, if successful, can help to detect cancers early and therefore increase survivability. This charity also runs indirect strategies like campaigns to reduce smoking, where a 1% reduction in smoking can save more than 3,000 lives annually. With 150,000 children taking up smoking each year and many continuing for the rest of their lives, they also run educational awareness courses to discourage the uptaking of this habit.

Perhaps the most important organisation involving the mitigation of cancer in the UK is the NHS itself. “Stoptober” campaigns for smoking raise money and make people 5x more likely to permanently quit. £200 million investments are resulting in much faster diagnoses turnarounds - a target of 2 weeks from the GP to the hospital, and 2 months from the GP to treatments commencing. GP training and support have provided access to quicker diagnosis turnarounds, and this is supplemented by screening. Breast cancer screening every 3 years for women aged between 50 and 71, alongside cervical screening at similar intervals for women between 26 and 64 years to catch the most common cancers. Additionally, vaccinations like the Year 8 HPV vaccine have been promoted.

However, the UK NHS system is seen as a “postcode lottery”, not just for cancers but all types of chronic diseases. Covid-19 has amplified and shown the vulnerabilities in such a system, with over 300,000 being on the national cancer waiting list, with 3.1% of these waiting more than 3 months. This is after being diagnosed with cancer! Understandably, this shows that many people’s cancer can progress despite referrals quickly from GPs. due to a lack of hospital availability. For every 4 weeks’ delay in treatment, there is a 10% reduction in complete survival likelihood.

The UK government also employ many indirect strategies. Smoking was banned indoors in 2007, alongside a 2-year increase in legal age, and also picture warnings on smoking packaging - the first EU nation to do so, helping the “tobacco control plan”. “Sugar taxes” have also been introduced throughout the past decade to remove up to 40% of sugar from cereals, banning buy-one-get-one-free offers in supermarkets, and requiring the calorie count to be shown in restaurants. Finally, the 10-year cancer plan with state-of-the-art radiotherapy machines and record investment to reduce the effects of an ageing population.

However the effectiveness of these remains limited - the purchase of sweets and unhealthy foods can still be undertaken, and the prevalence of smoking has not seen a substantial decrease since the Covid-19 pandemic, whilst the use of e-cigarettes has increased. Moreover, the lack of access to these new technologies in northern areas of the country has been revealed, on top of complaints about “red tape” and additional bureaucracy from importing them from the EU and internationally.

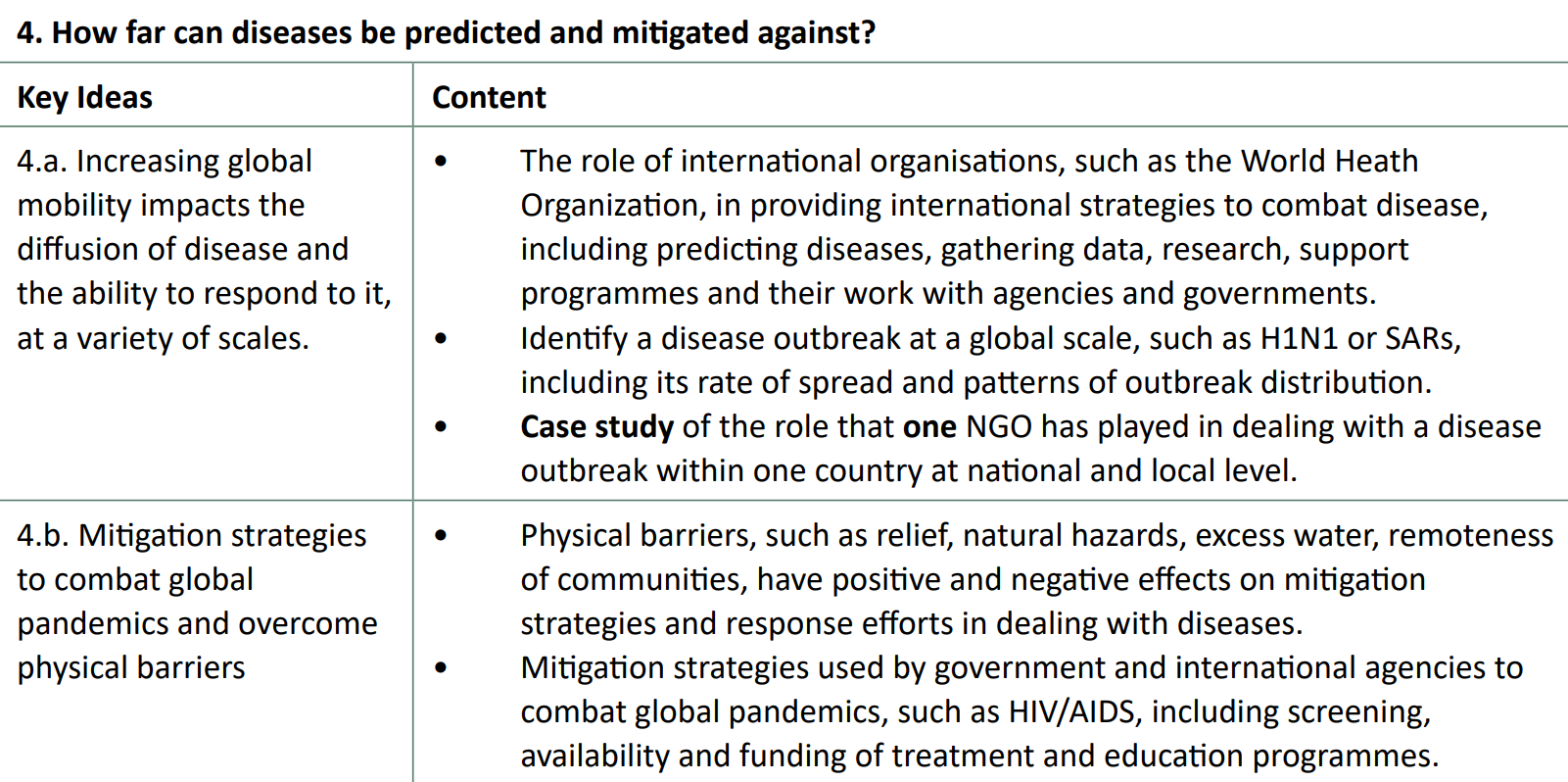

4. How far can diseases be predicted and mitigated against?

Case study: The Red Cross and cholera in Haiti

Haiti is known as “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere”. It has a GNI per capita of US $1665 PPP and poverty is around 60%. The Mw 7.0 quake in January 2010 killed around 10% of the population of the capital, Port-au-Prince. More than 90% of the population lived in slums and half had no access to toilets.

Nepalese aid workers stationed along Mirebalais, in the Artibonite river valley, are believed to have brought the disease, 9 months after the quake hit the island nation. 820,000 cholera cases were counted within 4 years, with around half a million hospitalisations - 82 hospitals had been damaged or destroyed during the quake.

The British Red Cross targeted the outbreak with its own response programme between 2010 and 2012. 10 days after the outbreak began, MSF found that the largest camp in P-a-P had no access to chlorinated drinking water, and the Red Cross were able to deliver clean water to 300,000 camp dwellers in the capital. On top of this, as cholera is water-borne, they built 1300 latrines, serving almost 200 people each. They also directly treated over 20,000 cholera cases in treatment units across Haiti, provided medical supplies to hospitals in the Artibonite Valley and indirectly combatted the disease through educational measures, teaching how to avoid infection and the symptoms.

Coupled with other aid workers like Cuban doctors who treated more than 75,000 cholera cases, it may have been a much greater success than it was. Weak governance contributed to the poor treatment of cholera in Haiti. There were over 10,000 NGOs but no effective management strategy and as a result, the easily-treated cholera was responsible for 10,000 deaths. [1]. Basic functionality and sanitation was not put in place across the country.

Further reading: [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

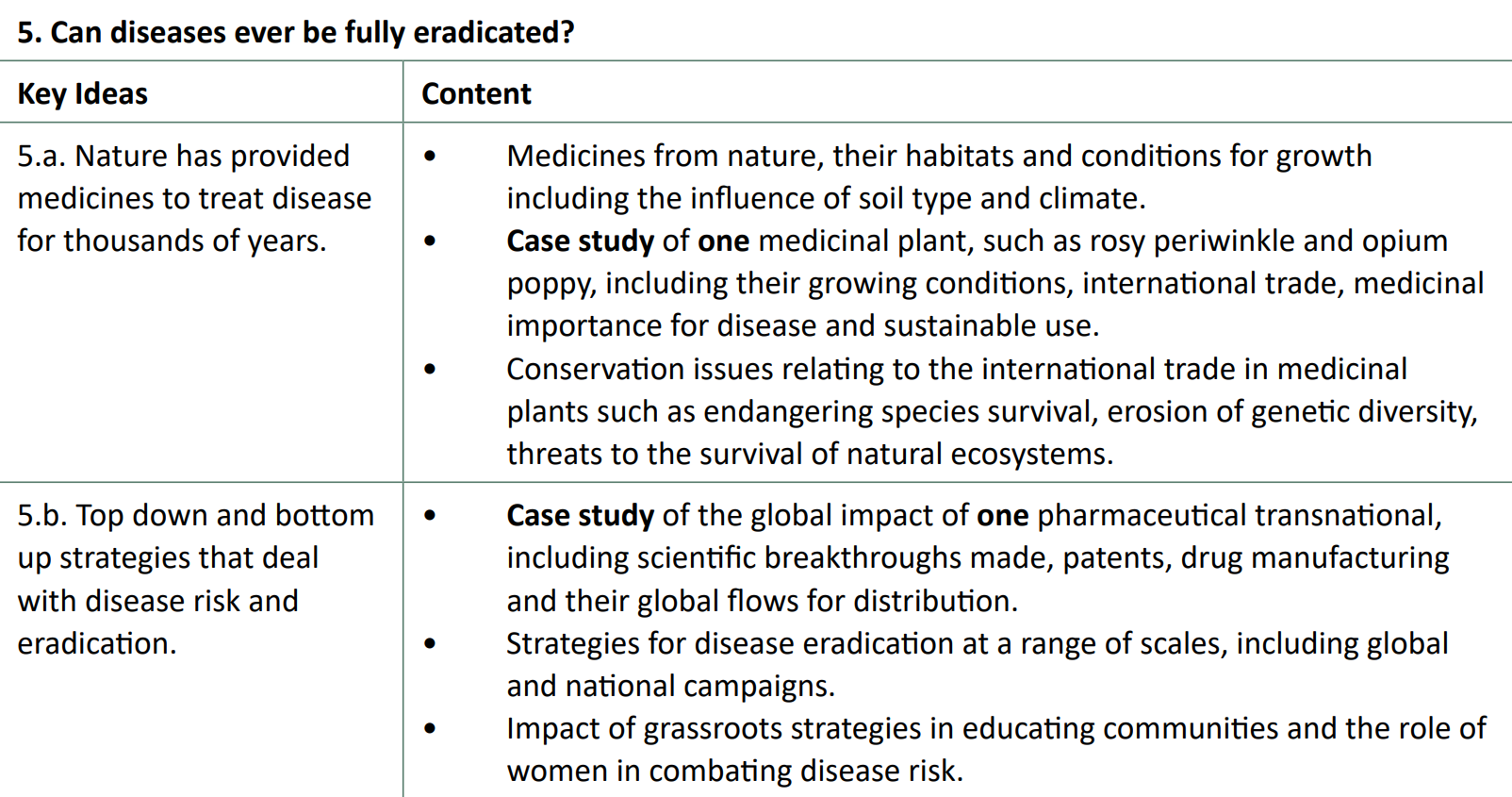

5. Can diseases ever be fully eradicated?

Case study: the rosy periwinkle

Plants have been used for a long time as medicines to cure diseases, from old herbal remedies in prehistory to the medieval Doctrine of Signatures.

The rosy periwinkle (or rosy p) leaves contain 70 alkaloids with significant medicinal value. Vincristine and vinblastine were preciously undiscovered by science. Vincristine is being used in childhood leukaemia: since 1970, survival rates have increased from 10% to 90%. Vinblastine can help testicular cancer, Hodgekin’s lymphoma and more. Furthermore, other alkaloids can be used to treat some cancers too. This has been unable to be synthesised synthetically through scientific means.

In Madagascar, where it is native, and in some areas of India and central Asia, huge land areas are being used to farm this plant. For Eli Lilly, its developer, sales equate to hundreds of millions of dollars from healthcare services around the world.

However, it is patented by Eli Lilly, which makes it illegal for others to sexually reproduce, import or export the plant. As a result, it maintains a monopoly over the periwinkle market and can effectively charge the prices they decide to use it. Furthermore, this also allows them to get away with biopiracy, as under 5% of the money is given back to the indigenous farmers. Economic growth is limited due to export restrictions under Lily which can exacerbate poverty in a region, as workers are effectively being exploited for transnationals’ gain.

Although it has come under scrutiny from some EU regulators, this practice largely goes unnoticed, as pharmaceutical companies have leverage and spend billions on discovering new drugs.

Biopiracy further reading: here

Case study: GSK (formerly GlaxoSmithKline)

GSK is part of the transnational pharmaceutical industry, which is a for-profit industry.

Historically, GSK has been (and may still be) overcharging governments and individuals for drugs, making abnormally high profits on lifesaving therapeutics. Its former employees have been criminally prosecuted on two continents, and have also been accused of lobbying governments and international organisations, with the use of bribing medical experts in favour of them. In addition, they have been seen to prioritise the R&D of drugs that require long repeated prescriptions and less those which are not as profitable like those needed for tropical diseases.

Despite these criticisms, GSK is able to deliver almost a billion vaccine doses and billions of medicine packs and healthcare products every year. 100,000 people globally are directly employed by them in tertiary and quaternary sector jobs, improving local economies in their 36 countries of manufacturing.

Some of GSK’s breakthroughs and patents include the first malaria candidate vaccine and ongoing Nobel Prize-winning discoveries for malarial drugs. They also provide medication for type 2 diabetes and discovered the first oncology drug for leukaemia. On top of this, they are one of the only pharmaceuticals to be actively researching new candidate drugs for the WHO’s top 3 global priority diseases. Patents in medicine last for no longer than 20 years and give GSK the ability to invest greater amounts in new medicines. They currently hold almost 10,000 patents, largely in HIV medication, cancer treatments, cardiovascular disease and Covid-19.

As GSK had an operating profit of £6.433 billion in 2022, they can afford to provide LIDCs and EDCs drugs and medicines at significant discounts: 80% of the 800mn vaccine doses given were to these countries in 2014. In addition, they do not enforce historic patents or file new medicinal patents in LIDCs, allowing companies to manufacture versions of their medicines in these countries. Finally, their code of practice now involves capping the prices of patented drugs in LIDCs, many of which cannot manufacture their own pharmaceuticals, to 25% of the UK price and only allowing a 5% return on each product sold - the remaining 20% of its profits are invested into the developing country where it is sold.

Mini case study: Guinea worm in Ghana

The Guinea worm eradication programme and the Ghana Red Cross women’s program partnered and women, who are typically the ones to source water for families, were taught about the benefits of filtering water to avoid contamination. Women were also responsible for reporting and monitoring all cases of the worm back to the WHO.

Note: Although not a case study, grassroots strategies should also be recapped (guinea worm)

1 ↩︎